KJIPUKTUK (Halifax) – I have two school-age sons who live with disabilities. I have endured a constant tug of war with institutions, from schools to the department of Education, from hospitals to Community Services to make sure that they receive a proper education and live a healthy life.

I have spent endless hours reading about disability, highlighting educational policies, completing disability support applications, and preparing for meetings in which I plead with institutions that seemingly uphold my sons’ rights.

See also: Sister-to-sister: an open letter to Minister Kelly Regan

This struggle is often interspersed by a deep anxiety: what would happen if I were not readily available to send this long email or to engage in endless conversations/fights with teachers, principals, civil servants and bureaucrats? And what will happen when I will not be here at all?

I imagine these thoughts are on all caregivers’ minds, but for family members who live with disabilities a life of poverty, homelessness, institutionalization, incarceration and social isolation is a lot more likely than it is for ‘normal’ ones.

My anxiety, however, is not limited to the future. I am deeply concerned about what is happening to children with disabilities today.

Because of their importance in children’s everyday life, schools are a primary source of this anxiety. Can schools really be a welcoming place for all students?

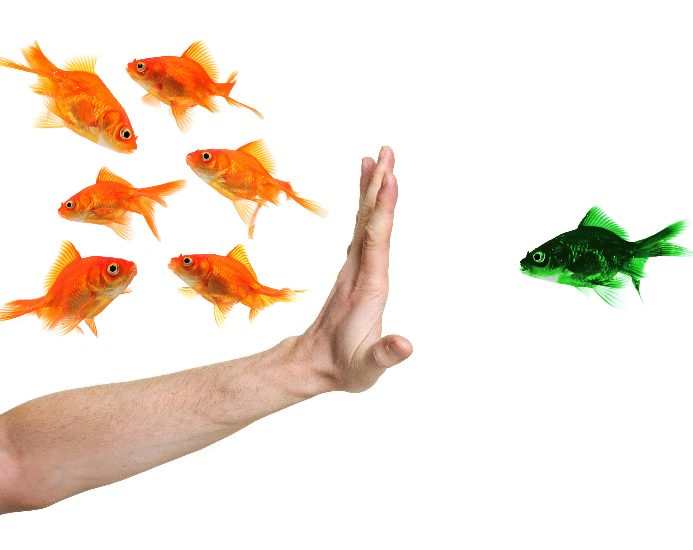

Some teachers complain that inclusive education is a failure and that it is impossible to educate all children in a classroom. But why is their gaze directed to children with disabilities, Indigenous children and children of colour?

Why do they refuse to see how education as a system is failing children who do not fit into the mould of children marked by “normalcy”, meaning white, middle-class, cisgender and heterosexual children without disabilities?

Wouldn’t it make more sense if, as parents, educators, administrators and politicians, we take a hard look at our educational and welfare systems that historically have been central to the Othering of all those who allegedly ‘pollute’ and ‘drain’ the system?

Perhaps considering the nature of our very own institutions would force us come to terms with our complacency and complicity to a system built upon ableist, gendered and racist notions of who truly belongs to the community.

While the talk of neoliberal restructuring, national cuts and the financial costs of welfare services are ‘real’, equally ‘real’ is our history as a nation of trying to ‘keep out’ all those who do not fit the mold of ‘legitimate and all-deserving’ Canadians.

As other women who are caregivers for children living with disabilities in this province and in the country, I live in a state of constant fatigue. I nonetheless refuse to silently be “the good mother” who will patiently care for her sons while, around her, educators, administrators, healthcare providers, bureaucrats and politicians pay lip service to equity and social justice.

While some time ago I believed that my sons’ well-being depended on creating an inclusive school community, I now think that it will take more than that to avoid poverty, homelessness, social isolation and institutional abandonment in their future.

If we care for our children and friends who live with disabilities, we need to broaden our horizons beyond the school. We need to come to terms with the fact that families with members with disabilities are trapped in an ableist society, one which is also deeply heterosexist, racist and classed.

It is a society that encourages the everyday violence – some more overt, some more subtle – against those who do not fit the profile of the ideal Canadian citizen.

If we want to fight for our children, we need to challenge the economic, social and cultural barriers that sustain the status quo, be it in schools, hospitals, government offices, or in other institutions that us and our children encounter our lives.

It is therefore high time that we, as caregivers and parents, begin to see the bigger picture of what exactly it is that needs to change.

The writer wishes to acknowledge the struggle of Beth MacLean, Joseph Delaney and the Late Sheila Livingstone for full inclusion resulting in yesterday’s partial victory at the NS Human Rights Tribunal.

With a special thanks to our generous donors who make publication of the Nova Scotia Advocate possible.

Subscribe to the Nova Scotia Advocate weekly digest and never miss an article again. It’s free!

For my son, simply being, being present, making friends, was more than enough; it was everything.