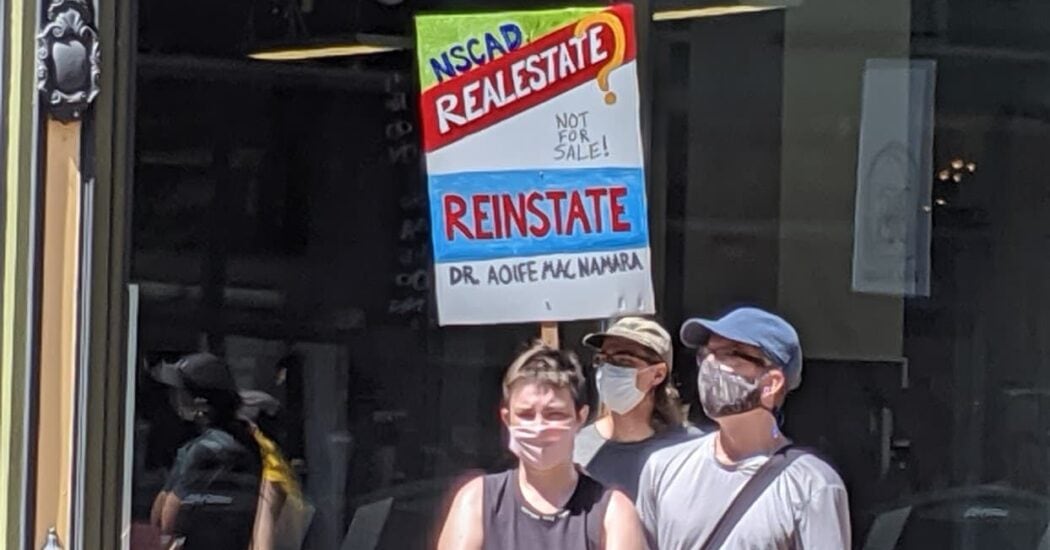

KJIPUKTUK (Halifax) – There’s been a lot of concern in recent weeks about the boards that are responsible for some decisions at Nova Scotia universities, primarily because of the abrupt end to the presidency of Dr. Aoife Mac Namara at NSCAD. The Minister for Advanced Education and Labour has declined to intervene: “’The government does not run the institution,’ said Kousoulis, ‘it is independent.’”

The autonomy of universities is a deeply entrenched principle, and for good reason. It ensures that universities build on their academic expertise rather than respond to the political dictates of a particular government and moment.

But over 90% of NSCAD faculty voted “no confidence” in the board; students have also been vocal in their opposition to the decision to end Mac Namara’s presidency. Aren’t they “the institution”? It seems that it is actually the boards that are independent, not the institutions for which they have limited oversight responsibility—responsibility usually centered, through legislation as well as broad practice, on finances and property. The board, for instance, doesn’t sign off on faculty research, course design, or thousands of other academic decisions that faculty make on a regular basis.

And, of course, many board members across the province are appointed by the provincial government. Of all of the committees and groups at a university, the board is by far the most entangled with government.

Dr. Mac Namara is not the first, and likely not the last, president to be shown the door. In 2011, David Turpin, then president at the University of Victoria, noted, “By my count, close to 20 percent of the AUCC membership has had a presidential term cut short” (AUCC is the Association of Universities and Colleges of Canada, now called Universities Canada).

Presidential terms have been no more stable in the past decade, and there were some high-profile examples: the University of Saskatchewan’s Board fired its president without cause in May 2014 and the president of the University of British Columbia resigned amidst concerns about an unsupportive board in 2015. More locally, the president of Cape Breton University was axed by its board in late 2016 and a president of Dalhousie University announced his resignation just as he was about to start his second term (he was reappointed in November 2017 for a new term to start July 2018, and resigned in June 2018).

These are all very different cases, arising from very different causes, to the very limited extent that we know what they are. A 2014 study of university presidencies in Canada suggested, however, that part of the reason for presidential terms being cut short is boards becoming more interventionist, “mak[ing] it more likely a disagreement with the president could occur.”

University presidents are in unusual positions. On the one hand, they are supposed to be the top person responsible for overseeing the university as a university: faculty primarily conduct research and teaching but also regularly serve supporting roles outside of the university, from advising government and other public institutions to collaborations with the private sector. On the other hand, presidents answer to boards that are dominated by non-academics.

If you take a look at university boards in our province, you will find a lot of similarities not just in their lines of work but also in the companies they work for: the large grocery and pharmacy chains; rental property companies; the larger corporate law firms; Emera and the Halifax Airport. Food, housing, power, and travel. We shouldn’t be surprised at the pressure to grow enrolment, especially enrolments from outside of Nova Scotia.

University presidents cannot effectively lead academic institutions if they are made precarious by boards that overreach or can be significantly driven by the focuses and assumptions of their day-jobs, rather than by academic expertise and the urgent needs of our classrooms, our labs and studios, our libraries, and our province—the whole province, in all its rich complexity and diversity. They cannot lead effectively if boards evaluate them in terms of the boards’ responsibilities rather than their role in the university community.

Universities are not independent if that independence begins and ends at the boardroom door, and can leave even faculty-supported presidents in the hallway.

For universities to truly be independent institutions of discovery, knowledge, and the advancement of civil society, the academic staff and students who are the university need to be returned to the centre of our vision of university autonomy. Boards and governments can start by listening when academics express profound concern as strongly as they have in recent weeks at NSCAD.

Julia M. Wright is George Munro Chair in English Literature and Rhetoric at Dalhousie University, and past-president of the Dalhousie Faculty Association.

See also: The place to draw the line is here – On NSCAD and the real threat to universities

With a special thanks to our generous donors who make publication of the Nova Scotia Advocate possible.

Subscribe to the Nova Scotia Advocate weekly digest and never miss an article again. It’s free!

Time to prepare? Schools need more teachers, smaller classrooms if the province is to avoid early closure and school personnel are to teach and learn in safety.