Halifax is known to Mi’kmaq as Chebucto “Kjipuktuk” or “Great Harbour”. Since time immemorial a number of Mi’kmaq Clans held permanent villages in Kjipuktuk. The Mi’kmaq of Kjipuktuk took advantage of the coves in the Harbour since they offered protection from the elements, a place to beach canoes, and a constant supply of fresh water from the streams flowing down from one of many lakes nearby. There was also a wide diversity of marine life in this area that provided food all year round, especially large marine mammals such as grey seals, Harbour seals and even Atlantic Walruses were plentiful.

Mi’kmaq territory was split into 7 Districts. The seven Districts we known as: Kespukwitk, Sipeknékatik, Eskíkewaq, Unamákik, Piktuk aqq Epekwitk, Sikniktewaq, and

Kespékewaq. Kjipuktuk was located in the Sipekne’katik District. The District of Sipekne’katik in English is translated to the “ground nut place” or “place of the ground nut”. The word for ground nut in Mi’kmaq is “Sipekne’”.

Mi’kmaq lived in family groups comprised of a number of families that were usually connected by kinship. These groups would make up a Clan and each Clan was represented by elders and a local Sakamow (chief).

Local Clans were interconnected through kinship ties and blood relations. These interconnected Clans all shared a specific territory known as a District. Each District held boundaries that were expected to be maintained by the Chiefs of each Clan with the assistance of war captains. Each District also had a head Sakamow known as a “Nikanus” or District Chief, and all seven Districts was represented by one “Kji’saqmaw” or Grand Chief.

The District Chief was appointed by all the chiefs and elders from each clan in his district. This District Chief was always a Chief that had won many victories against enemies of the Mi’kmaq. He was also a shaman who did ceremonies like fasting and sweats, and he would have carried a pipe which he earned through ceremony. To earn the right to carry a pipe you would first have to fast for 4 days and night with no food nor water. At end of the fourth day you would be pierce thru your chest with bone attached to sinew rope and strung up to a tree and pulled off the ground and held off your feet until the bone ripped thru your skin. Through this process it is believed that you die and enter the spirit world and only thru suffering and pain are you abled to be pulled back out of the spirit world to this world and thus bringing with you the knowledge and teachings of all those who have gone before you. Only then did you earn the right to carry the pipe. You would repeat this process for four years in a row to earn the right to pore the water on the rocks in a sweat lodge ceremony.

The territory of local Sakamow seems to have been coextensive with the area occupied by the inhabitants of a single village. There were three Clan Sakamows in Kjipuktuk with a population thought to be around 400 to 600 Mi’kmaq’s by the early to middle 1700’s. Considering anthropological evidence in other areas and the plentiful food supply in Kjipuktuk the population was probably in the 2000 range. Along the southeastern bank of the St. Croix River in St. Croix, Hants County there is evidence there was a large permanent Mi’kmaq village that supported well over 500 and possible 1000 Mi’kmaq’s at any given time. The main source of food on this river was Eel and Gaspereau.

Considering the large amount of fish and marine life in Kjipuktuk the Mi’kmaq population would have been much larger at the time of contact. During the 1500’s it was common knowledge among fishing vessels to avoid entering Kjipuktuk because the Mi’kmaq would attack any outsiders entering the basin. In his memoirs Monsieur Samuel De Champlain wrote that he avoided going near Kjipuktuk even though he identifies it on his maps as Baye Saine or Healthy Harbour. The islands located at the mouth of the Harbour were known to the French as Les Mortes (The Death) where a number of French Sailors were killed by the Mi’kmaq of Kjipuktuk. Any ship entering would be met by over 400 warriors in canoes who would immediately attack the unexpected ships. Many of the ships that entered Kjipuktuk during the late 1500’s and early 1600’s were never seen again. By the mid-1600’s European sailors and fisherman avoided Kjipuktuk all together. So the exact number of Mi’kmaq in Kjipuktuk during these early years is unknown.

The area of downtown Halifax up to Point Pleasant Park was known to the Mi’kmaq as “Amntu’kati”, which in English means, “spirit place” or “the place of spirits”. This is also the place where Mi’kmaq believed the Great Spirit Fire sat whose sparks gave birth to the 7 original families of the Mi’kmaq people. This is told in the seventh level of creation in the Mi’kmaq Creation Story. In the seventh and last level of creation it is told of how the Mi’kmaq came to be and at the time of their creation and they were divided into 7 families which later became the 7 districts of Mi’kmak’ik. Every year since time immemorial the Mi’kmaq from all over Mi’kma’kik would come and gathered at “Amntu’kati” for 7 days after the first full moon during “Tquoluiku,” “the frog croaking month” in the spring. The Mi’kmaq would come to this ceremony to celebrate the creation of the Mi’kmaq people. This is why the Mi’kmaq protected Kjipuktuk so fiercely.

With the increase of European fishing boats anchoring along the shore lines of Mi’kma’kik, contact with Mi’kmaq increased. These early contacts had a devastating consequence on Mi’kmaq population since the Mi’kmaq had no initial immunities to the diseases brought to them by early contact. As a result of these early contacts the Mi’kmaq numbers in Kjipuktuk slowly decreased and they could no longer protect Amntu’kati like they once did.

In 1746, the Mi’kmaq of “Kjipuktuk” along with hundreds of warriors from the Sipekne’katik District and neighboring District’s along with over a dozen Chief’s waited for Duc d’Anville fleet of over 70 ships bringing supplies of arms, ammunition, along with over a 1000 soldiers to fight the English. Before departing France some of the crewmen on those ships had been infected by European Borne Viruses and illness. Fueled by the crowded, unsanitary conditions, along with poor food, and polluted water on the ships, many died on route from a deadly combination of scurvy, typhus, and typhoid. By the time 40 ships of the original 70 arrived a large number had perished. The Mi’kmaq of “Kjipuktuk” and the warriors of Sipekne’katik were expecting ammunition and supplies but instead they were greeted by an armada of death and destruction. Hundreds of Mi’kmaq’s died in “Kjipuktuk”, oral traditional accounts state the numbers of Mi’kmaq deaths were well over 1000. They were buried along with over 1000 French sailors and soldiers in two mass graves. The ones that survived spread the deadly combination of scurvy, typhus, and typhoid all across Mi’kma’kik, which ended up killing over one-third the entire Mi’kmaq population.

Mi’kmaq oral tradition records the catastrophe that decimated their numbers. Many died on their traditional camping grounds, where they were quickly buried. The Mi’kmaq called the disease “the black measles,” even naming one of their camping areas “Iktuk’maqtawe’g’aluso’l”, the “place of the black measles.” Before the arrival of English settlers, the Mi’kmaq camped in the sheltered coves around “Kjipuktuk” Bedford Basin. One such cove, Birch Cove was used as a semi-permanent camp by four or five families. As a base for resource extraction, Birch Cove was perfectly situated and the upper cove an ideal camp site.

The Mi’kmaq people were well organized with highly complex social and political structure and prepared to defend their District at any cost. If Duc d’Anville fleet never brought with them an armada of deadly disease and illness to “Kjipuktuk” in 1746, Cornwallis would have never been able to settle there, only 3 years later. Especially considering as previously noted, this area was highly sacred to the Mi’kmaq of Sipekne’katik

The English first settled in Halifax on June 14, 1749. This enraged the Mi’kmaq. The spot where they built their settlement was sacred land to the Mi’kmaq. On August 14, 1749, Cornwallis called for a meeting with the Mi’kmaq and neighboring Tribes. It was crucial for the English to sign a Treaty with the Mi’kmaq especially with the Mi’kmaq of Cape Sable Island. The English needed a treaty to end the hostilities in Annapolis Royal and the constant attacks at English settlements in Maine and New England. However, Mi’kmaq of Sipekne’katik refuse to come to this meeting, instead the Chiefs and Elders of Sipekne’katik drafted a letter to Cornwallis expressing their anger over the English settlement in Kjipuktuk, and in doing so the Mi’kmaq were asserting their rights to their lands.

The letter in part to Cornwallis stated: “The place where you are, where you are building dwellings, where you are now building a fort, where you want, as it were, to enthrone yourself, this land of which you wish to make yourself now absolute master, this land belongs to me. I have come from it as certainly as the grass, it is the very place of my birth and of my dwelling, this land belongs to me the Mi’kmaq (Lnuk), yes I swear, it is God (Niskam) who has given it to me to be my country forever … Show me where the Mi’kmaq (Lnuk) will lodge? You drive me out; where do you want me to take refuge? You have taken almost all this land in all its extent. Nothing remains to me except Kchibouktouk (Kjipuktuk). You envy me even this morsel…Your residence at Port Royal does not cause me great anger because you see that I have left you there at peace for a long time, but now you force me to speak out by the great theft you have perpetrated against me.”

Cornwallis refused to accept the Mi’kmaq claims to Kjipuktuk, so the Halifax settlement remained. In September, less than a month after Cornwallis received the letter, the Mi’kmaq started attacking the settlement of Halifax. These attacks on the Halifax settlement was clear message to Cornwallis that this land belong to the Mi’kmaq of Sipekne’katik. Even more so, the Mi’kmaq had already previously warned the English in 1720, that they will attack anyone who settled in their land without their consent.

On October of 1720, three Chiefs, including the District Chief of Sipekne’katik, met with the French in Les Minas. The Chiefs included Chief of Pisiguit, Minas, and Shubenacadie. The Chiefs requested the French to draft a letter for them and have it sent to Governor Richard Phillips stationed at the English Garrison in Annapolis. The letter was a warning to the English to stay in Annapolis and stay out Mi’kmaq lands in Sipekne’katik. The contents of the letter in part stated: “We believe Niskum “God” gave us these lands. However, we see you want to drive us from the place where you are living (Annapolis), and you threaten to reduce us to your servitude…..we are our own masters and not subordinate to anyone….we do not want English living in our lands (District of Sipekne’katik). The land we hold only from God. We will dispute with all men who want to live here without our consent.”

After receiving the letter in Annapolis, the English kept entering Sipekne’katik territory. So in keeping with their warning the Mi’kmaq started repeatedly attacking the English. From 1722 to 1726 the Mi’kmaq attacked and destroyed over 100 English ships. After suffering many losses, the lieutenant-Governor of Annapolis, Captain John Doucett, wanted to make peace with the Mi’kmaq so finally a “Peace and Friendship” treaty was signed in 1726.

However, Cornwallis did not heed the warnings nor did the English want to accept Mi’kmaq sovereignty over their sacred lands of Kjipuktuk, so in response to the Mi’kmaq attacks on the Halifax settlement Cornwallis gave the order for all his military under his power, to attack and kill any Mi’kmaq on site. The date of this order was October 01, 1749. Cornwallis included a bounty of 10 Guineas for every Mi’kmaq scalp produced to commanding officers at Annapolis, Minas and Halifax.

Skirmishes between the Mi’kmaq of Sipekne’katik and English continued for three years. The Mi’kmaq responded by declaring war on the English. So the Mi’kmaq started launching a series of destructive attacks against Protestant settlers in the Halifax area. Eventually Cornwallis was forced to resign in failure and replaced by Governor Peregrine Thomas Hopson in August 1752. One of his first priorities was to make peace with the Mi’kmaq. Governor Hopson sent messages to the Mi’kmaq of Sipekne’katik that the English wish to make peace and lifted the bounty Cornwallis had out for Mi’kmaq scalps. What is most interesting is the response received by Hopson from the District Chief of Sipekne’katik, Chief Cope. Chief Cope felt that the Mi’kmaq of Sipekne’katik should be compensated for the lands settled in their district. Chief Cope stated: “the Indians should be paid for the land the English had settled upon in this country.” These words are clearly demonstrating Mi’kmaq assertion of title, especially when they are asking for compensation. Although the Council did not address Chief Cope’s proposal for monetary compensation for the lands settled on by the English, they did recognize the lands still controlled by the Mi’kmaq as their own lands by the words written in the treaty. “We will not suffer that you be hindered from Hunting, or Fishing in this Country, as you have been used to do, and if you shall think fit to settle your wives and children upon the River Shibenaccadie, no person shall hinder it, nor shall meddle with the lands where you are.”

Although the Mi’kmaq signed a treaty of Peace and Friendship with the English settlers, Kjiputuk, the Great Harbour will always hold a significant value to the Mi’kmaq people since it truly is Amntu’kati – the place of spirits.

“Legend of the Sweat Lodge”

The Halifax Peninsula where Point Pleasant Park now sits was known to the Mi’kmaq as Amntu’kati, which in English spirit place or the place of spirits, and Amntu’apsi’kan is the Sprit Lodge, if you follow the Halifax Peninsula around it comes to a small cove that is protected by the rough seas, it is Wejkwe’tukwaqn which in English means “to come to a legend” or “where the legend comes from”, it is the place where our Legendary Warrior Amntu’ resides at his Lodge and Guards the Eastern Door to protect the Lnu’k, the people from any dangers that come from the open sea. The Armdale Rotary derives its name from Amntu” which is pronounced Arm-en-doo.

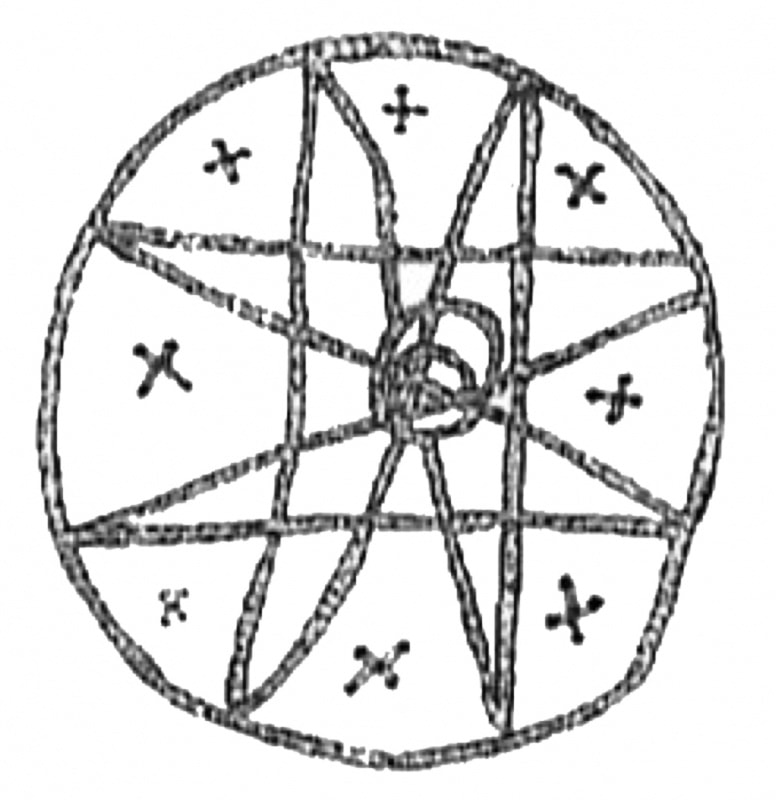

The Hill that overlooks the Bedford Basin where the Mi’kmaq 8 point star Petroglyph is located was known to the Mi’kmaq as Wejkwapeniaq which in English means “the coming of the Dawn”

it is where Wa’so’q ji’j or as some call him Wasok-gek who is the brother of Amntu, would come and sit upon the hill and wait for the dawn to approach before he continued on his Journey to see his Brother Amntu’ at Amntu’apsi’kan.

Wa’so’ql’ ji’j means “little heaven” and Amntu’ means “the spirit”.

While sitting on the Hill of Wejkwapeniaq admiring the rising sun and the coming of the dawn to start a new day, the great spirit Niskum came down from Wa’so’q (Heaven) to speak Wa’so’ql’ji’j and reminded him that the Lnu’k (The People) of Mi’kma’kik (The Land of the Mi’kmaq) are the keepers of the eastern door and we must always remember that we came from Grandmother Earth and when our time is done on Earth our bodies must go back to Grandmother but our spirits will rise and sit with our ancestors, Ms’it No’kmaq (all our relations) in Wa’soq.

So to honor where we all came from we must go back into the womb of the Grandmother and cleanse ourselves with the Grandmother life giving Blood Samqwan (the water).

So Wa’soql’ji’j asked Glooskap (the son of Grandmother Earth) to gather all the leaders of the 7 Districts of Mi’kma’ki to come to Wejkwapeniaq. After hearing these instructions from Glooskap, the great Chiefs of all 7 Districts along with their greatest leader of them all “the Grand Chief of all 7 Districts came to Wejkwapeniaq to meet with Was’soq’ji’j and his brother Amntu’. While they sat in counsel, Was’soq’ji’j and Amntu shared with the great Chiefs the teachings of the “Amntu’apsi’kan” – “the spirit lodge”, and told them that Amntu’apsi’kan represents the womb of our grand mother earth and you shall come and sit in council to cleanse yourself and honor the ancestors who have gone before you and be humble and the spirits will come and give you guidance so you may lead your people in a righteous way.

You shall pray to each of the 4 directions, for each direction there is 7 “Nu’kuntew” (lava rock or grandfather stone) since these are the oldest of all stones. There will be 7 Nukuntew’s for each of the 7 districts making a total of 28 Nu’kuntew. You shall heat the Nukuntews or grandfather stones till they are red hot. These grandfather stones are our grandfathers, they have no eyes, no ears, no mouth, so the one who pours the water onto them also speaks for them. Each person shall pray out loud so that your prayers may be heard by “Ms’it No’kmaq” (all our relations). When your prayers are done you shall end it with Ms’it No’kmaq as a reminder that we are all related and connected to the spirit realm!

So the 7 great chiefs of all 7 districts crawled into the womb along with their greatest leader of them all the Grand Chief of all 7 Districts.

The Grand Chief did as he was instructed by Was’soq’ji’j and his brother Amntu’ and poured the water on the hot grandfathers and as the hot steam rose from the grandfathers, the Chief’s cleanse them-selves so that their minds may become empty of all things that are bad and harmful. During the ceremony the ones that have gone before them came to the Chief’s and gave them the teachings and instructions of our ancestors, all our relations. Ms’it No’kmaq!

At the end of the Amntu’apsi’kan Ceremony Was’soq’ji’j and his brother Amntu’ instructed the 7 District Chiefs to take the Amntu’apsi’kan teachings back to each of their districts, where they shall send out 4 of their most spiritual elders to go in all 4 directions and pass the teaching of the Sweat Lodge Ceremony onto others!

The Mi’kmaq Creation Story – the 7th level of creation

In the Mi’kmaq Creation Story there are 7 levels of creation. In the seventh and last level of creation it is told of how the Mi’kmaq came to be and at the time of their creation they were divided into 7 families which later became the 7 districts of Mi’kmak’ik. The Mi’kmaq Creation Story in part goes as following:

The Creator who sat in Wa’so’q, created the first born, Na’ku’set, “the Sun”. The Creator also sent a bolt of lightning across the sky that created Wskitqamu – “the Earth”. From that same bolt, Glooskap was created out of the dry earth. After being created Glooskap laid upon Wskitqamu, on his back with his feet and hands pointing to the Four Directions. From another bolt of lightning came all living things that walked. Crawled, and swam. The vegetation was also created from this same bolt.

Glooskap watched the living things move about the world freely and wished to have the same freedom. So the creator granted his wish and sent out a third bolt of lightning which allowed Glooskap to stand and move freely on the Earth.

The Creator then sent Nukumi, Glooskap’s grandmother, to teach him how he should live. She was created from a rock transformed into the body of an old woman who became his Elder. Glooskap and Nukumi traveled the Earth. They met his mother, Níkanaptekewísqw, who share the knowledge about the cycles of life and the future. Born from a leaf on a tree, she brought love, wisdom and the colors of the world.

One day Kitpu the eagle spirit came down from Wa’so’q to speak to Glooskap. He told Glooskap that soon He and his grandmother had to leave this world and travel to the west and to the north and there they shall enter the spirit world. As Kitpu spoke to Glooskap the Creator sent down another bolt of lightning which created a blazing fire.

Then Kitpu told Glooskap, that the fire created by this final lightning bolt is the Great Spirit Fire. It sits in in “Amntu’kati” – “the Spirit Place or Place of Spirits” While you journey to the Spirit world, your mother and nephew shall look after the Great Spirit Fire. After 7 winters have passed a spark will fly out of the Great Spirit Fire, and when it hits the earth, a woman will be created. And another spark will fly and another woman will be created, and then another spark will follow, until 7 women are created. And then, over time, more sparks will fall out, and then 7 men will be created. And together these 7 women and 7 men will form into the 7 families of the Mi’kmaq people.

The 7 families will then disperse in 7 different directions. Once the 7 families reached their destinations, they would further divide into 7 clans that are related by kinship. Each of the 7 original families and their 7 clans would have their own “Maqamigal -wutan” or “territorial area” for their subsistence, so they would not disturb the other Families.”

Each of the 7 Originals families will have a Nikanus Sakamow or Head Chief, and each of 7 clans will have their own Sakamow “Chief”. Each of the 7 Nikanus Sakamow will represent all the 7 Sakamow’s of his family in his Saqamawutis – territory of the head Chief and this will be known as his Kmitkinu – “District”. And all 7 Kmitkinu Nikanus Sakamow’s – “District head chief” will be represented by one “Kji’saqmaw” or “Grand Chief”. After 7 winters have passed each of the 7 Nikanus of the 7 original families along with their Kji’saqmaw would return back to the place of the “Great Spirit Fire” in “Amntu’kati” where they will celebrate for 7 days in song and dance over the creation of the Mi’kmaq people.

And each spring following the first, the 7 leaders of the 7 original families will return with their kin back to Amntu’kati after the first full moon of “Tquoluiku,” “the frog croaking month” and celebrate for 7 days. During these 7 days, all the people will dance, sing and drum in celebration of their continued existence in Mi’kma’kik.

Click here for a version of this article that contains footnotes.

If you can, please support the Nova Scotia Advocate so that it can continue to cover issues such as poverty, racism, exclusion, workers’ rights and the environment in Nova Scotia. A pay wall is not an option since it would exclude many readers who don’t have any disposable income at all. We rely entirely on one-time donations and a tiny but mighty group of kindhearted monthly sustainers.

Thank you so much for sharing my article I feel honoured to have this venue to share the history, stories and legends of my people!

That’s awesome I am so honored to have read this article about our history and thank you for sharing!

Our history needs to be written out more often, since so much of it is still oral history. Wtg Mike

beautiful story proud metis

Michael, Very interesting and important research. Did you come across any specific information related to the Mi’kmaq and McNabs Island or Father Pierre Thury, the missionary that the Mi’kmaq reportedly buried on the island in 1699?

Actually I do, father Thury wrote in his memos about the gathering that occurred every spring! He attempted to it into a Christian gathering as he converted more Mi’kmaqs over to Christianity. I have some material on father Thury some where in my stack of research material.

There were a few Mi’kmaq families living on McNabbs island right into the early 1900’s. Sadly the last Mi’kmaqs living on McNabbs island were killed during the Halifax Explosion.

Thank you Michael. This is interesting information about Father Thury… Please contact us so we can update our McNabs Island historical records. info@mcnabsisland.ca

Thank you for sharing this! I found it to be a great read! Looking for as much info as I can to regain the history and culture my ancestors were stripped of.

wela’lin ms’it No’kmaq.

PRESS RELEASE: White Man who supports the Native Community

Don Kane

8 Armada Drive

Halifax NS

B3M 1R8

902-457-1299

nodenak@gmail.com

===================================================================================================

I’m a White Man who supports the Native Community with their request of moving the Cornwallis statue from where it now stands in

the city-owned park. It should be placed on military land in the North End of the city in front of the Military Museum on Military

property. The city of Halifax is named Halifax, not Cornwallis.

My name is Donald W. Kane. I live in Halifax Rockingham area, where the French landed on June 22, 1746. The Mi’kmaq supported and

aided these people through their disastrous days. Many Mi’kmaq died because of European passed diseases. Yet they were human enough to aid others in need.

My Great Grand Father was James Kane. He polled his vote in favor of Confederation in 1867 in Halifax. He lived in the north end of the city. He remembered when the North End of City was sparsely settled. He was a retired army man. At one time foreman of works for streets for the City of Halifax. Kane Street and Kane Place are named after him. He had cows in those pastures in the North End of the city.

For sixty-three years Mr. Kane had lived in the Halifax North End and was a great booster for that section of the city. He had watched it grow, saw vacant fields turned into houses and streets, and he believed that if Ward 4, 5, and 6 had their just due, Halifax North would be and thus a wonderful part of the city to live in. He was a strong supporter of those who ask that the streets be put in proper command thus encourages people to brighten up their home surroundings.

His son had a store in the north end that bartered and traded with both the Black and Native communities. They brought their wares into the store, rabbits and deer, baskets and other handmade products. White people came to the store to buy these products. Both the Black and Native communities sold their products in the Halifax markets during the growth of Halifax. They still do today! Both of these groups are as much a Canadian or Haligonian as much as any other nationality that exists in Halifax. Their voices should be listened to and heard.

In the late 1970’s and early 1980’s, the Military had a World War II Tank on the Halifax Commons right beside the children’s

water pools and play area. For years it got painted pink. Each year the Military would start the spring by repainting it green. After a

number of years of this painting exercise, the Military finally moved it to its proper place. It was moved over beside the Military

Building on the other side of the Halifax Commons.

Why was a Military WW II Tank in the middle of a Children’s playground? Why is a statue of a Military Butcher in the middle of a Halifax

City owned park? The City owned park should be renamed “Speakers Park”. Where the statue of Cornwallis stands now there should be a platform there where anyone can stand and give personal views to any public that wants to listen.

Daniel N. Paul, a Mi’kmaq historian is right that all Haligonians should be aware of the “Cornwallis’ scalping proclamation”.

==========================================================================================================

TAKEN FROM WIKIPEDIA

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Edward_Cornwallis

Early History on Cornwallis:

Cornwallis played an important role in suppressing the Jacobite rising of 1745. He fought for the victorious British soldiers at the Battle of Culloden and then led a regiment of 320 men north for the Pacification of the Scottish Highlands. The Duke of Cumberland ordered him to “plunder, burn and destroy through all the west part of Invernesshire called Lochaber.” Cumberland added: “You have positive orders to bring no more prisoners to the camp.” Cornwallis’s campaign was later described as one of unrestrained violence. Cornwallis ordered his men to chase off livestock, destroy crops and food stores. Cornwallis’s soldiers used rape and mass murder to intimidate Jacobites from further rebellion.

Mi’kmaq Beliefs today:

The appropriateness of prominent memorials to Cornwallis has been controversial; it has been argued that—despite his significance to provincial history—that Cornwallis should not be given such prominent recognition due to his actions against Mi’kmaq civilians. A notable critic against such tributes is Daniel N. Paul, a Mi’kmaq historian; Paul argued that Cornwallis’ scalping proclamation was not as widely discussed as it is in the present day and that the increased availability

Hello Michael, your research was very interesting and informative. I work for Fisherman’s Cove in the Heritage Centre in Eastern Passage and at the Heritage Centre we are planning on adding a First Nation’s exhibit. Do you have any possible sources or contacts that could help us with acquiring information for our plans?

There are a number of organizations that would help! Perhaps try CMM (Confederacy of Mainland Mi’kmaqs)

The Tarr Center in Sipekne’katik First Nations may also help provide assistance!

I could also assist you if you like just shoot me an email at michael.mcdonald@dal.ca

PRESS RELEASE: White Man who supports the Native Community

Don Kane

Please email me Michael

nodenak@gmail.com

I have more information for you.

I loved reading this article. Time for anther spring gathering to teach the people the stories again!

Fantastic article Mike. Thank you so much for writing and sharing. This is the history that is missing from the textbooks of classrooms and perhaps if it was taught and learned by all there would be more of an “informed” discussion regarding the significance of the lands we today call Halifax.

Thank you Mike for making your work available to us. What a great history lesson!!!! I am a proud Metisse and so grateful for any knowledge about the Mi’Kmaq people (my ancestors). So often Native American culture has been so misrepresented. Much honor and respect to you. Thank you again.

Thank you for sharing Michael. I do believe the bone puncture comes from the prairies culture. Sweats we did do, but not to burn for pain. Glooscap is a French word for Good Captain. Jesuit priests did not want to disrespect their King by calling our leaders Kings, so they called them Good Captains. Glooscap stories are based on actions of Grandchief Tuna and his grandson and great grandson John Denny. Tuma was originally from Cumberland county located across Halifax. Because of the war he moved his family to Cape Breton and Nfld where he became Grand Chief in those areas. His grandson fought back and reclaimed our land all the way back to Restigouch. Back then, what we called Unamákik- Nfld, PEI, NS, NB, parts of Quebec and Maine was called Nova Scotia by the white man.

Kathy, actually bone piercing was a common practice with a number of eastern woodland first nation groups. It was only done by Shamans, so only a small select few would go through this ceremony process. They would be pulled up into a tree. There is historical data documenting this practice. The prairies groups pierced as well but the ceremony and the process of piercing was different but the purpose behind it was the same.

Many first nation groups adopted ceremonies from each other for thousands of years and then made it their own. It is foolish to think that only the sweat ceremony was the only ceremony shared. Your comment reminds me of what an elder once told us when I was a kid in the early 80’s when I would attend sweat ceremonies. Back then there was only a few lodges around and mostly it was a hidden practice. The elder was a hard core Christian and she said to us, “Why are you all doing that sweat lodge stuff anyways, it isn’t our way, it is the plains Indian way”. It was kind of ironic her saying this since she was practicing a religion that belonged to the Europeans who adopted it from the middle easterns. As it turns out, the oldest sweat lodge ever discovered was found near the La’have river outside Bridgewater that was carbon dated to almost 3600 years ago. The Mi’kmaq 8 point star is actually a blue print to a sweat lodge. Sweat Lodge ceremonies we used by first nation groups all across the America’s. its makes you wonder where did it originate from since the oldest one was found here. We are the keepers of the Eastern door.

Excellent article Michael, as it provides a balanced view of the history of Halifax during the colonial period. Of particular interest to me is the relationship between the French (Acadians) and the Mi’kmaq prior to the arrival of the English in 1749. Without their assistance, the Acadians may not have survived in the New World. Contrast that with the way the French and Mi’kmaq were treated by Cornwallis and the British. Because of this shared history, I will always have a special place for the Mi’kmaq people.