The CCPA’s 2017 Report Card on Child and Family Poverty in Nova Scotia, published in partnership with Campaign 2000, is a reminder of how broken our social contract is, and of the urgency to fix it. What values should be prioritized and what rights should be upheld? Weaving together a strong social contract and building healthy communities requires us to ensure everyone, no matter who they are or where they live in our province (indeed, our country), is offered meaningful opportunities to live in dignity.

Behind those annual report card numbers are real families struggling to provide healthy school lunches, pay for school supplies and fees throughout the year, support their children in activities and sports, and to buy winter coats and boots. It is difficult for many to pay the minimum delivery of home heating oil, or to find and pay for child care. After paying housing costs, there is little money left over for food, let alone anything else.

While the data can’t tell us the full impact of our broken social contract, it can provide us with some parts of the story.

By the numbers

It has been 28 years since the Canadian House of Commons passed an all-party resolution to end child poverty by the year 2000. Child poverty rates in Nova Scotia and across Canada have fluctuated over the years since this resolution, but the goal was never achieved. There has been a 16.3% decrease in child poverty rates from 2000-2015 in Nova Scotia; however, the percentage of children living in low-income circumstances in 2015 is still 19.3% higher than it was in 1989—when the promise to eradicate child poverty was made.

With over one in five children under the age of 18 living in poverty, 21.6% of Nova Scotian children are living in families with incomes below the After Tax Low Income Measure (AT-LIM). Since 2014, the child poverty rate in Nova Scotia decreased by less than 1% (to 22.5%), or 1,600 children.

For children under the age of six in Nova Scotia, poverty rates were even higher than for those of older children; 26.2%–close to one in three–lives in poverty. Those early years are critical for development, and each one that passes represents a significant loss of opportunity to ensure their success and well-being, now and into their future.

Government transfers do help

The data also clearly shows that government transfers help. A lot. In 2015, we saw a 32.5% reduction in child poverty due to government transfers, without which 17, 350 more children would live in poverty in Nova Scotia for a total of 53,220 (instead of the current 35,870 number).

Nova Scotia, ranked 6th in Canada, is the least effective at reducing poverty among Atlantic provinces. The amount that government transfers reduced poverty in 2015 was the same as 2014–and therein lies the problem. The continued erosion of public services and income supports rather than necessary robust public investment tied to the cost of living takes a toll on everyone, especially those who need these programs and supports the most.

One positive change, still yet to be revealed in the data, is the effect of the federal government’s Canada Child Benefit in 2016. This investment is undoubtedly having a positive impact, but we should be under no illusion that this will end child poverty, especially given the depth of the problem.

In families for whom government support is the only source of income, 100% live in poverty. With total welfare incomes in Nova Scotia remaining flat since 1989 (adjusting for inflation), the amount of support puts these families far below the poverty line; 40% below, for some families.

The numbers are striking. Low-income couple Nova Scotian families with two children living with government supports only had a median annual income of $36,426, or $9,866 below the poverty line. Couple families with one child experienced a poverty gap of $9,762 per year. Lone parent families with one child were living $9,568 per year below the poverty line. Low-income lone parent families with two children had a depth of poverty of $10,312 per year—meaning they would need an extra $859/month to bring them up to the poverty line.

Our most vulnerable children

This year we are also able to benefit from the additional information provided by the mandatory long form Census, which has not been available to us for 10 years (It’s notable that this won’t be available again for another five years, which points to the need for more disaggregated data based on race and ethnicity and not just related to poverty).

The Census data reveal distressingly high rates of poverty among visible minority children (37.4%) including 67.8% of Arab children, 50.6% of Korean children and 39.6% for Black children.

While some Black children would be new immigrants and non-permanent residents, 71.5% of this population report having lived in the province for three generations or more (according to Census 2016).

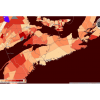

It is notable that the postal areas that are loosely associated with communities predominantly made up of African Nova Scotians have similarly high poverty rates (East Preston at 38.9% and North Preston at 40%).

Nova Scotian immigrant children, with a poverty rate of 40.3%, are far worse off than non-immigrant children at 21.2%. Over half (56.8%) of new immigrants coming to Nova Scotia between 2011 and 2016 were in poverty. Over half (50.5%) of non-permanent residents (children of persons who have a work or study permit or who are refugee claimants) were living in low-income families.

One in four Aboriginal children (excluding those on reserve) in Nova Scotia live in poverty, according to Census data. The child poverty rate calculated using T1 Family Files taxfiler data shows very high child poverty rates in postal areas that include First Nations reserves including 72.7% in the Eskasoni postal area, 68.8% in the Micmac rural route, 48.5% in Membertou, 43.8% in Afton, 44.2% in Whycocomagh, and 40% in Wagmatcook postal areas respectively.

Poverty rates vary depending on family size and type as well. In 2015, almost half (48 %) of the children living in lone parent families in Nova Scotia lived below the AT-LIM (representing 23,400 children) compared with 10.6% (or 12,470) of children living in couple families. In 2015, children living in female-led lone parent families had a poverty rate of 48.9%, compared to 30.4% for children living in male-led lone parent families. The poverty rate for children in families with three or more children was 28.4% in 2015.

Given the depth of poverty in our province, the high number of families impacted, and the complex connections between poverty and historical inequalities, significant investment in families and children is necessary. We cannot afford to wait for the data. Our children need and deserve swift urgent action.

Comprehensive poverty reduction plans

healthy and to develop their potential towards full participation in society. While more investment in income support is needed, targets and timelines for comprehensive, robust poverty reduction plans must be developed by all levels of government, in collaboration with those experiencing poverty, community groups, First Nations governments and Indigenous organizations.

These plans must:

- Address the legacies of colonialism and racism

- Invest in more services and supports for newcomer immigrant families

- Uphold children’s right to child support

- Increase and improve system of federal transfers for social services

- Include progressive family tax policy

- Fund a well-designed, affordable early learning and childcare system

- Ensure fair income for work

For our anti-poverty efforts to be most effective, our government must develop public policy solutions that take into consideration these differences in order to get at the root causes of poverty. This is the only way we can build a new social contract.

Dr. Lesley Frank is CCPA-NS Research Associate and an Associate Professor in the Department of Sociology at Acadia University. She has co-authored or single authored the Child Poverty Report Card for Nova Scotia for thirteen years.

Dr. Christine Saulnier is the Nova Scotia Director of the Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives, and co-author of the 2017 report card.

This article was originally published on Behind the Numbers.

If you can, please support the Nova Scotia Advocate so that it can continue to cover issues such as poverty, racism, exclusion, workers’ rights and the environment in Nova Scotia. A pay wall is not an option, since it would exclude many readers who don’t have any disposable income at all. We rely entirely on one-time donations and a small group of kindhearted monthly sustainers.