KJIPUKTUK (Halifax) – On 9 December, an arbitration board delivered its decision on a collective bargaining dispute between the province and its direct employees (civil servants) represented by the Nova Scotia Government and General Employees Union (NSGEU).

Strangely, both sides have lauded the board’s decision. How could that be? I will argue below that the arbitration award continues, arguably worsens and certainly vindicates McNeil’s throttling of the unions.

The arbitration board was empanelled last summer. Unlike teachers and health care workers, provincial civil servants do not have the right to strike at all and are subject to binding arbitration for all unresolved bargaining disputes.

But under the terms of the Public Services Sustainability Act (Bill 148) arbitration boards have their hands further tied: they can award no more than the government’s four-year pay mandate. Several trade union groups, including NSGEU, are challenging Bill 148 in the courts for its constitutionality. The Supreme Court of Canada has previously ruled that collective bargaining and the right to strike are Charter rights and that in the absence of strikes, free and unfettered arbitration must prevail. But unless and until the law is struck down (and I hope it is struck down), it is the law.

When the arbitration decision was announced, the CBC reported Premier McNeil saying that the award is “a fair deal that his government can afford.”

But the trade union movement claimed that the arbitration board had “broken the government’s wage restraint agenda”. News reports claim that the deal is “more lucrative” than the one proposed by the province. And some predict that the award will set the trend for other public sector bargaining units in the post-Bill 148 era.

So, for whom is the arbitration decision a victory? To be fair, the union had no choice in this matter and did the best it could in the circumstances. But it is incorrect to claim that it is a victory for them.

The arbitration award follows the dictates of Bill 148 (and the deal imposed upon the province’s teachers) for the four years 2016 to 2019, just as the province ordered. But the arbitrators tacked on a further two years, which is outside of the scope of Bill 148. The arbitrators pointed out that a shorter term would land labour and management back in negotiations too soon.

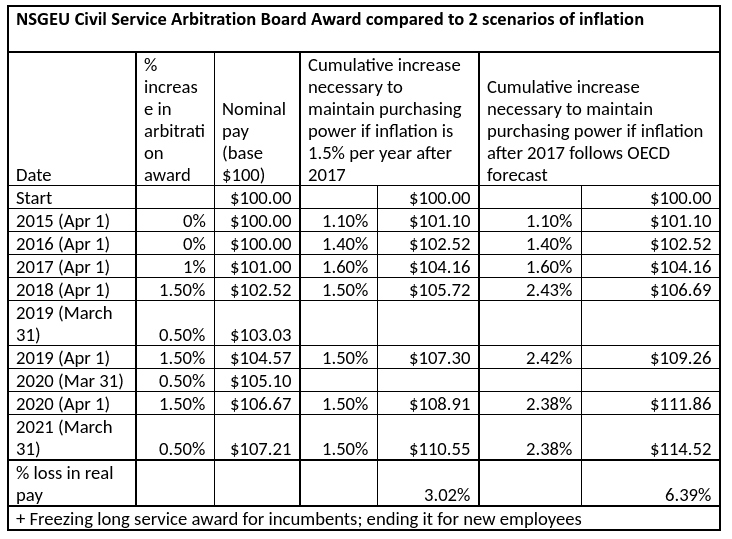

Here is a summary of the monetary part of the arbitration decision:

- 0 per cent increases in 2015 and 2016.

- 1 per cent increase effective April 1, 2017.

- 1.5 per cent increase effective April 1, 2018

- 0.5 per cent increase effective March 31, 2019.

- 1.5 per cent increase effective April 1, 2019

- 0.5 per cent increase effective March 31, 2020

- 1.5 per cent increase effective April 1, 2020

- 0.5 per cent increase effective March 31, 2021

- Freezing of the long-service award for current employees; ending it for new employees

News outlets are reporting that this amounts to a 2% wage increase in the final two years, as if the workers involved are 2% better off than they were at the start of the period. They are not. That is lazy and possibly reprehensible reporting. Here are some big problems with all such reporting:

- The first problem: It fails to account for the compounding effect. In other words, you can’t just add up wage increases. You must account for the following fact: if I get a 1.5% raise this year and a 1.5% raise the next year and a 1.5% raise the year after that, I have NOT received a 4.5% increase over three years. I have, in fact, received a 4.5678% increase. So simply adding up the annual increases, UNDERSTATES slightly the actual amount of the nominal pay increase.

- A much worse problem is one that OVERSTATES considerably the effect of the arbitration award. And that can be summarized in one word: INFLATION. If I get a 1% “raise” this year but the Consumer Price Index has risen by 1.5%, then I have, in fact, received a CUT in my “real” wages by .5%. I am .5% less able this year to afford things I could afford last year.

If we apply these provisos to the arbitration decision, what does it show? Compared to their pay on the last day of their old collective agreement, civil service workers’ real pay at the end of the new collective agreement will be between 3.02% and 6.39% LOWER than when they started.

And that’s not taking into account the freezing (and removal for new employees) of the “long-service award.” It is difficult to put a figure on this loss. But a loss it surely is. Under the scheme, the government contributed every year to an eventual payout for employees upon retirement or death. That contribution is nothing less than deferred wages, just like a pension or other insurance plan. Its removal is a removal of wages. However large the real pay cut, the loss of those annual contributions amounts to a larger pay cut.

What is the take-away from all this take-away?

After the teachers dispute and Bill 148 the unions are desperate for even a semblance of a victory, Technically, the new arbitration decision does step outside the boundaries of Bill 148. If that’s a victory, it is surely a hollow one.

Another reason for lauding the arbitration is presumably that it shows that the government’s full-on hatred for third-party decision-making was unfounded. “See,” the argument seems to go, “You had no reason to fear arbitration. Arbitrators are not unpredictable pro-union types, they’re not scary, they are reliable.” Judy Haiven and I have made a similar argument in earlier publications, but we are more critical of arbitrators. We assert that arbitrators by and large side with government restraint of public sector workers as part of a general capital-led attack on the working class. Third-party intervention should not be seen as a panacea, but rather highly suspect.

We call for direct negotiations with full power of sanction for both parties.

“…The parties themselves are in the best position to solve [their differences.] We are not saying that third-party intervention is never helpful in labour relations. Indeed, it has a long history in Canada. But third-party intervention is not a blanket solution to labour disputes. It works best only under certain conditions. Four questions determine just how effective intervention can be. First, is the intervention voluntary (i.e. have the parties themselves agreed to it) or has intervention been thrust upon them by government fiat? Second, is the intervention binding e.g. does the intervenor have the power to impose his or her solution upon the parties, or are the solutions more in the way of recommendations?

“Third, is the intervention permanent or temporary? Fourth, are the issues complex, difficult, and costly or are they relatively straightforward, simple and inexpensive? We contend that the more compulsory, the more binding, the more permanent the intervention and the more complex, difficult and costly the issues, the less effective intervention will be for the unions. On the other hand, the more voluntary, suggestive and temporary the intervention and the more marginal the issues, the more effective intervention can be.”

If the courts do strike down Bill 148, that will likely confirm only that arbitrators should be allowed to resolve labour disputes in the absence of the right to strike. Moreover, this arbitration board’s decision will indeed likely form the basis of its post-Bill 148 wage agenda. How convenient!

Appendix:

Let’s look in more detail at the arbitration award. The first column shows relative dates; the second group of columns shows the cumulative increase awarded by the arbitrators; the third group of columns shows the cumulative increases necessary to maintain the employees purchasing power assuming inflation of 1.5% per year after 2017; and the fourth group of columns shows the cumulative increases necessary to maintain purchasing power under an alternative scenario of inflation. The 13th row shows the loss in real pay under the two inflation scenarios.

Just how much of a pay cut civil servants will get depends on the rate of inflation after 2017. Nobody actually knows what the inflation rate will be. But we have some indications. We have been in a relatively low inflation period. But it has not been negligible. For the past several years, inflation has run at about 1.5%. That may not seem like much, but there is a reverse compounding effect at work. For example, $100 earned in 2010 is now worth $89.69 or 10.31% less. If my cumulative pay increases over those years are less than 10.31%, then I am making less than I was in 2010.

In the case before us, we present two scenarios of inflation. In both of these scenarios, we know the year-on-year rate of inflation for 2015, 2016 and 2017 and we include those. For the years after 2017, the first scenario simply assumes a regular 1.5% increase in the cost-of-living. The second scenario assumes higher inflation, using estimates provided by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD.)

There are several reasons to choose the second inflation scenario. For the past several years, the government and the Bank of Canada have deliberately tried to keep interest rates and inflation low in order to stimulate economic growth during the recession that began in 2008. But now that Canada’s economy is showing signs of health, inflation will surely be allowed to and will likely rise. One reason for low inflation in recent years has been the crisis in the petroleum sector. But, as the sector recovers, the cost of petroleum will also rise. Recent reports also predict that the cost of food is set to rise. These and other factors will likely boost the cost-of-living higher than 1.5% per year.

Even the second scenario makes modest predictions about inflation. But the message of both scenarios is clear: Barring a full-scale revolt, the real pay of public sector workers in Nova Scotia will continue to drop.

Larry Haiven is professor emeritus of the Sobey School of Business, Saint Mary’s University.

Good on you, Larry. Oh, the power of spin!