KJIPUKTUK (Halifax) – Just around the time Nova Scotian kids and their parents were navigating the start of a new school year (a particularly rocky start for the many who take school buses) innocuous seeming opinion pieces appeared in several eastern Canadian newspapers. These articles claimed kids in Atlantic Canada “aren’t getting access to the educational choices they deserve” and touted “an innovative solution right here in Canada: charter schools”. They were written by Paige MacPherson (new Atlantic director of Canadian Taxpayers Federation – an organization devoted to reducing taxes) and her claim is that charter schools will provide more school choice for parents, superior academic results and, on top of it all, save money for taxpayers. All these claims, and more, can be found in a new research paper put out by AIMS, the Atlantic Institute for Market Studies, coincidentally authored by Macpherson herself.

However, time for a quick reality check. In Alberta, there are almost no charter schools in rural areas. Charter schools and the “school choice” model, are generally an urban phenomenon, because a high population density is required to support competing schools within feasible travel range. In Nova Scotia, where many school districts face declining enrolments, rural areas often face the problem that their only school may not have enough students to stay open at all. In areas which can only support one school, even when students spend hours every day on a school bus to attend, “school choice” is a ridiculous concept – and more than 50% of students in Nova Scotia live in small towns or rural areas. Although parts of downtown Halifax and perhaps Sydney, may be able to support several competing schools, these are essentially the only places in Nova Scotia where “school choice” is a practical possibility. Given this reality, locally based school boards have historically been the way in which parents could have input into their children’s schooling. However, Nova Scotia has just eliminated school boards (another AIMS idea). In an era when small rural communities are often losing their schools the idea that charter schools will increase parents’ choice or input into their children’s schooling is laughable.

Even for major metropolitan centres, Macpherson ignores the fact that great diversity is provided within the public systems of large cities like Toronto and Vancouver where parents can choose from a wide variety of alternative schools. If school choice is what she values, why doesn’t she call for Halifax and other large Atlantic cities to adopt a Toronto style system of public alternative schools?

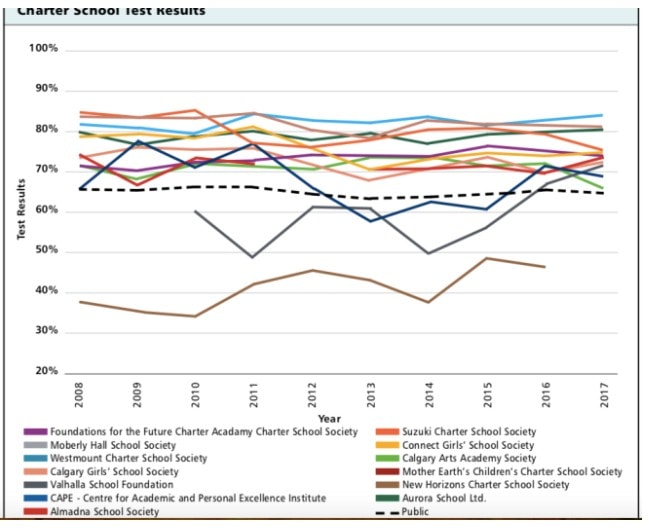

Her second claim, that charter schools will produce superior academic results is also suspect. Using the Fraser Institute “report card” on schools (whose validity is also highly suspect), MacPherson claims that the 13 Alberta charter schools outperform the over 1000 public schools, and uses this graph:

Apart from the fact that any standardized test scores show only one aspect of a school’s worth, there is no explanation of what test results she is actually using from the past 10 years or why she doesn’t use the handy “mark out of 10” that the Fraser Institute uses to grade schools. She dismisses (without providing evidence) the well-founded objection that charter schools attract children from “an engaged demographic” and that this “may skew standardized test scores”. She maintains that the Charter Schools handbook states “charter schools cannot turn students away, if they have the capacity to take them on” so therefore they cannot be elitist. This is completely disingenuous as anyone familiar with the lengths education-savvy parents will go to get their kids into the “best” schools.

And as for saving money for taxpayers, MacPherson speculates that if 50% of Alberta students were in charter schools, the government would save over a billion dollars a year. What this wishful thinking completely ignores is that private and charter schools can select the students who will have the least problems and they can rely on the public system to develop curriculum that they can use. The public school per pupil amount covers the cost of the department infrastructure, including all the specialists and curriculum developers that are part of any education system. The major way charter schools could save money is by cutting the largest education expense of all – teachers’ salaries. And that would mean undermining teachers’ unions, which is what Grant Frost, in his excellent article, maintains is one of the real motivations behind this push for charter schools.

It’s interesting that MacPherson doesn’t use examples from the US or Britain, where charter schools or their equivalent have been operating on a much larger scale than Alberta for the last few decades – and where there is a large literature evaluating rigorously (and mostly negatively) the claims of the charter school movement.

I have spent some time in Britain recently investigating the “academization” that started there about 20 years ago when “failing” schools (mostly in poor neighbourhoods) were taken over, sometimes by private interests, and made into “academies”, which were basically charter schools with a huge injection of cash. I have written about this in previous blog posts.

Although the hype at the start was that academization would give disadvantaged students access to the best education, what has actually happened is that 20 years later there is basically no difference in academic standards between academies and schools that have remained in the public system, but lots of evidence that segregation between privileged and disadvantaged students has deepened. And has all this produced better results across the board? On international comparisons, such as PISA, test scores have only marginally improved.

What also happened was that Britain went from having 152 Local Education Authorities (school boards) to over 3000 Multi-Academy Trusts (MATs) plus the LEAs, all with their administrative structure, their school governors and bureaucratic systems. The cost of education has ballooned, while individual schools have been starved of resources, particularly the Local Authority schools. And where has all that money gone? Much of it has gone to the private interests that support and run these Multi-Academy Trusts.

So, after 20 years of academization in Britain, education costs have soared, the gap between the economically advantaged and disadvantaged has widened and internationally comparable test scores show little change. Academies haven’t worked in England, and they won’t work here. So why are AIMS and its relatives like the Fraser Institute still promoting charter schools in Canada? Stay tuned for part 2 for what I think are some of the real reasons behind this push.

This article was originally posted on Molly Hurd’s blog: The Inquiring Teacher. It’s re-posted here with Molly’s kind permission.

Molly Hurd’s perspectives on education have been developed out of her wide variety of teaching experiences in northern Quebec, rural Nova Scotia, Nigeria, Tanzania and Britain. She was also a teacher and head teacher at Halifax Independent School for twenty years. She believes passionately that keeping children’s natural love of learning alive throughout their school years is one of the very best things a school can do for its students. She is the author of “Best School in the World: How students, teachers and parents have created a model that can transform Canada’s public schools” published by Formac Publishing in 2017.