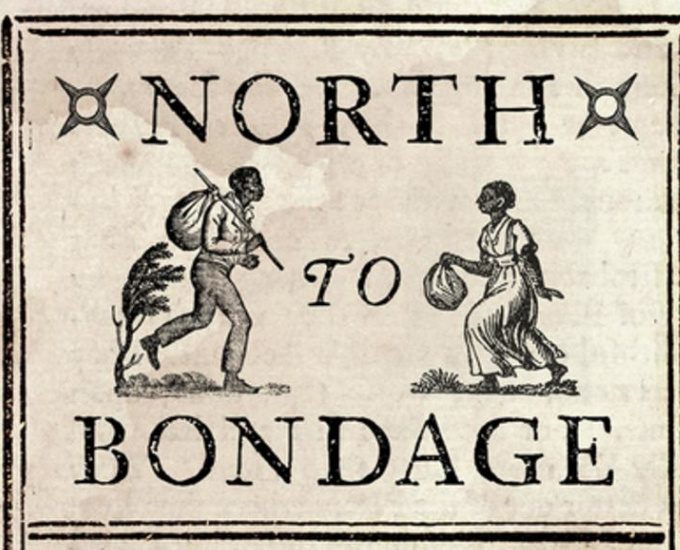

KJIPUKTUK (Halifax) – A book about slavery in Nova Scotia and the Maritimes, North to Bondage: Loyalist slavery in the Maritimes, by professor Harvey Amani Whitfield, shows how ownership of enslaved Blacks was widespread in the Maritime provinces, and a major contributor to its economic viability.

Whitfield describes how the enslavement of Black people goes back to the days that the French settled Louisburg, and continued after the British founded Halifax. It increased substantially with the influx in the 1780s of white Loyalist refugees, whose enslaved African Americans often traveled on the very same ships boarded by free Black loyalists.

How many Black Americans were enslaved is difficult to establish. Whitfield estimates that at its height there were some 2500 enslaved Blacks in the Maritimes, perhaps as many as 1600 in Nova Scotia. That may not sound like a lot, but keep in mind that in 1790 Nova Scotia had a population of only 30,000.

Slave ownership in Nova Scotia was widespread among both the rich and what today we today would call the middle class, farmers, store owners, artisans, etc. Maritimers typically owned one or two enslaved African Americans per household, seldom more than 5. They were forced to work in a variety of ways, as domestic help, labourers or skilled tradesmen.

Relationships between owners and enslaved Blacks, living in close quarters, was more intimate than on large plantations in the South, but that does not mean that lives in the Maritimes were better for enslaved Blacks.

Black women were often subjected to terrible sexual abuse, many enslaved Blacks were cruelly beaten, and families were routinely broken up and even very young children were sold as if they were mere commodities.

However, and this is significant, Whitfield also describes how on occasion there was sufficient space to fight back. At times enslaved Blacks could negotiate with slaveholders to better their working and living conditions. Or they managed to run away at great peril, witness the many advertisements about runaway slaves that have survived. There are even rare occasions of enslaved Blacks taking their owners to court, and (even more rarely) winning.

Slavery in our neck of the woods was never legal in the strict sense of the law, and rather than ending with a bang, it just sort of petered out, By 1820 it was virtually non-existent, Whitfield writes.

Whitfield is one of the first historians to tackle the history of slavery in the Maritimes in a systematic fashion. Slavery is a awkward topic for white society, it makes Canada look just as bad as our Southerly neighbour, and that’s no doubt why it took so long for this field of study to gain a foothold.

I highly recommend this book, but hope that people will read it not just to satisfy their curiosity about something that happened long ago, but also to reflect on the way the aftershocks of slavery continue to reverberate in Nova Scotia today.

It’s because of the contributions of enslaved Black Americans that many white settlers were successful, Whitfield argues in the book.

Meanwhile, although slavery formally ended, what never really disappeared in Nova Scotia is the notion that Black people are inferior, somehow less human. Slavery may have ended by the 1820s, but racism was only starting.

Whitfield’s book is an invitation to think hard about the historic roots of contemporary anti-Black racism, about the damage it has done and continues to do to African Nova Scotians, and about the way white people benefit from it.

In short, it’s an invitation for white Nova Scotians to start a serious conversation about reparations.

North to Bondage, : Loyalist slavery in the Maritimes, by professor Harvey Amani Whitfield. UBC Press

With a special thanks to our generous donors who make publication of the Nova Scotia Advocate possible.

Subscribe to the Nova Scotia Advocate weekly digest and never miss an article again. It’s free!

Robert!

You might like this page

https://novascotiaatlas.blogspot.com/p/book-of-negroes.html

Gus