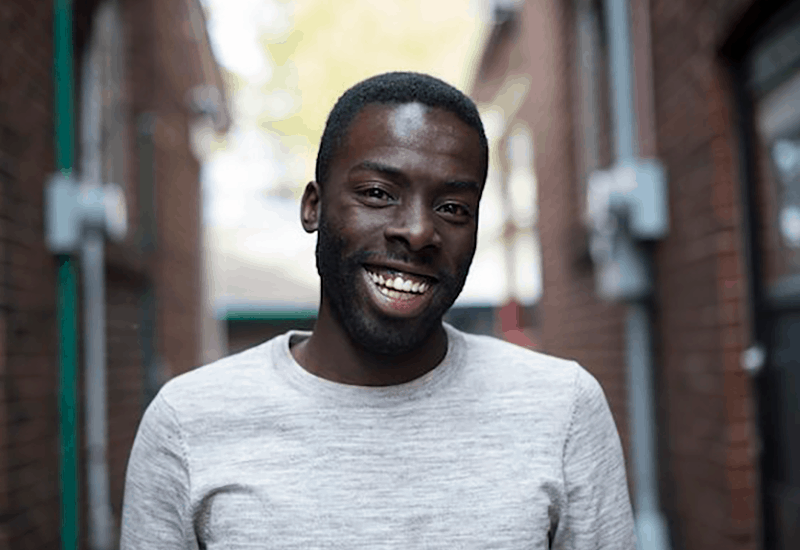

Kjipuktuk (Halifax) – We interviewed Toronto journalist, writer and community organizer Desmond Cole, who has been involved in the fight against carding in Toronto for many years.

Police in Ontario has been every bit as racist in their interactions with citizens as their counterparts here in Nova Scotia. It just all came out in the open a bit earlier. As a result Cole has direct experience with a temporary moratorium and subsequent halfhearted efforts to regulate the racist practice.

In other words, there are lessons to be learned from Ontario.

See also: Weekend video: The skin we’re in

This Saturday, April 27, Cole will facilitate a community workshop on street checks, community organizing, and resisting the state at the Bus Stop Theatre in Halifax. It starts at 1 PM.

Are there parallels between Nova Scotia and Ontario in terms of how the police check story has unfolded in the two provinces?

Yes, and the parallels are quite notable. First of all, just as in Ontario, Black communities in Nova Scotia have been telling the government of Nova Scotia for decades now that police are disproportionately targeting us. And just like in Ontario, the government chose not to listen until media and activists forced the release of information contained in the police’s own database.

The information became undeniable once white people chose to listen to people in authority, people like Scott Wortley, decided that they would like to believe these numbers on a piece of paper, rather than listen to Black human beings all along. At that point the government has responded with shock and horror, saying “oh my gosh, we can’t believe that this is happening and we’re so appalled.”

Finally, another parallel is that rather than at this point simply stop doing police checks, the government of Nova Scotia is trying to find a way to continue the practice.

The province recently announced a temporary moratorium, the police will not be allowed to stop people solely based on their race. Of course the Charter of Rights and Freedoms already tells the police that they cannot stop me based on the colour of my skin. So to announce that you’re not going to do that anymore is to admit that that’s what you’ve been doing the whole time.

Again based on the Ontario experience, what do you expect will happen in Nova Scotia next if we’re not alert?

I expect that the government of Nova Scotia will change the way that it records this information, so that we don’t have such an easy time in the future doing what we’ve done now, which is pulling their own numbers and exposing the racist bias. Meanwhile, they will continue to say that they stopped doing these random street checks now, that it’s all more targeted.

Well, that’s silly and the reason it’s silly is because there is no way to verify what the police are doing. It just as it was before, you have to take their word for it. There’s no independent verification, you can’t prove a negative.

So they’re going to point to a regulation that suggests that they removed racial bias, and there will be some kind of nonsense anti-discrimination training. And then they’re going to call it a day and go back to what they were doing before.

However at this point the community won’t have the documentation tools that we’ve had in the past to prove what the police are doing. It’s actually quite sinister.

What is it that makes this racism systemic?

When you look at the data anywhere around the country, whether it’s Halifax, Ottawa, Montreal, Toronto, Mississauga, Hamilton, Regina, Edmonton, Calgary Lethbridge, or Vancouver, we have data for all of these cities that shows that Black and Indigenous and other racialized groups of people are disproportionately the targets of this practice. Yes, we can pretend that that’s a coincidence, but it’s just an unavoidable truth.

One of the ways that police have tried to justify this practice is by saying that it’s only happening disproportionately to Black people because Black people often live in high crime areas.

That is false because you’re not engaging in street checks if you’re called to investigate a specific crime that is allegedly being committed by a specific individual, you’re responding to a call and you’re investigating a crime. So this whole idea of a high crime area is simply a justification for the free-for-all. You create these so-called high crime areas, and you end up with an area where everyone is basically fair game to the police.

Another factor here is that in a city like Toronto the most disproportionate carding activity in terms of Black people being stalked actually occurs in majority white neighborhoods. White communities have always been taught to call the police when they see Black people in their neighborhoods. The very presence of Black people is suspicious. And so what we see in Toronto is that in areas like the downtown core, where almost no Black people reside, a Black person is 17 times more likely than a white person to be pulled over by the police.

Why is the police so reluctant to give up carding, and why are politicians so tentative?

That is a question that is at the heart of all of this. Why are the police so interested in documenting Black people? Well, if they always know where we are, if they always know where we live, if they always know where we’re going to and coming from, then it gives them the ability to control us. The police won’t give this up simply because they’re asked to.

Despite what’s being said every municipality in Nova Scotia that has a police commission has the ability to regulate this practice of carding out of existence.

Besides, it would have been incredibly easy for the police commissioners in Halifax to say we are choosing a new Chief, and one of the requirements for the job application is that you have to tell us up front that you are willing to implement an end to this practice. And you won’t get the job if you can’t commit to that.

The success of any initiative to curb or ban carding really relies on politicians’ willingness to listen to the communities that are affected. You either listen to the communities who are being victimized by your police and you do something about it, or you trivialize their experience.

Unfortunately, we continue to see too much trivializing of the experiences of Black people and Indigenous people and other racialized people. What is lacking is a recognition of who the real experts on this issue are.

Edited for clarity

With a special thanks to our generous donors who make publication of the Nova Scotia Advocate possible.

Subscribe to the Nova Scotia Advocate weekly digest and never miss an article again. It’s free!