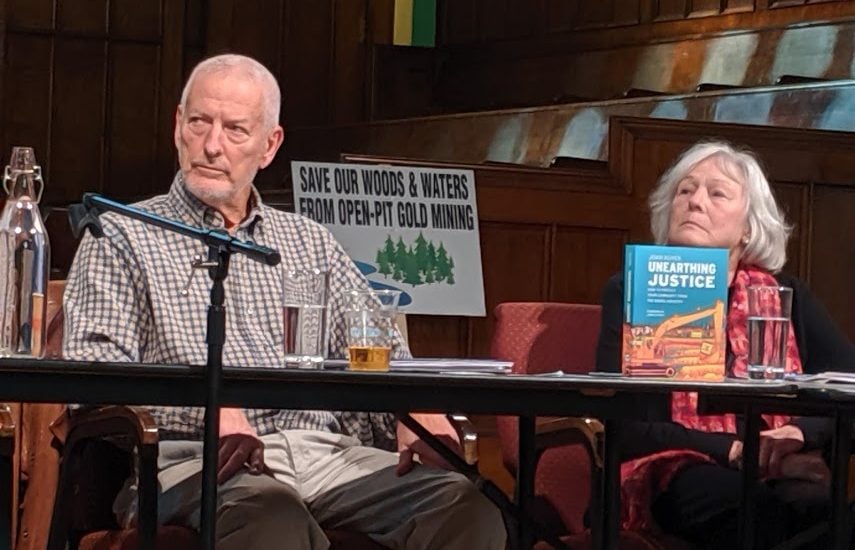

KJIPUKTUK (Halifax) – If not gold mining, then what? That was the question moderator Joan Baxter asked Peter Puxley at the Water not Gold panel on mining at St. Andrews United Church in Halifax last Saturday.

It’s the same the question politicians and mining proponents tend to ask, rhetorically, in defence of mining and other types of resource extraction, clearcutting comes to mind. The question there suggests that a few short term jobs is all people in rural Nova Scotia should hope for, and the ecological and environmental cost is simply the price we have to pay for these jobs.

Puxley, a writer, policy consultant and founding member of the Campaign to Protect Offshore Nova Scotia, in his response to that question, shows there are plenty of alternatives to, and all what’s lacking is mostly political will and courage.

Nova Scotians must insist on a different economic strategy. A strategy that invests in the priorities of our communities, not those of corporate lobbyists. We need an economic strategy built on restoration and sustainable development of our traditional sectors – the fisheries, agriculture, forestry, adding alternative energy, conservation, tourism and marine-based industries, for starters.

I argue that the economic pay-off is bigger – in decent jobs, and the high quality of life our treasured environment affords.

This is a strategy that empowers municipal-level government as the instrument of democratically directed change in this very rural province.

What might we have achieved with the same public investment in support of sustainable alternatives?

I hope to paint a plausible picture of a sustainable future. For our purposes, I would like to concentrate on food production, though I believe the lessons there apply to other sustainable sectors.

Extraction or sustainability?

First, a few statistics comparing the impact of traditional marine-based industries to those of that extractive giant, the oil industry.

In 2016, 17,500 people were employed in Nova Scotia’s fishery. Another 43,000 earned their living in the tourism sector. Leaving aside boat- and ship-building and other marine-based activities, compare those numbers to the 300-400 direct jobs the oil industry provides in a good year, or even to that industry’s own over-blown estimate of 3,500 jobs.

Similarly, the revenue contribution of the extractive oil industry pales by comparison with that of traditional industries.

The value of seafood exports in 2018 totalled $2 billion, of which lobsters accounted for $1 billion. Tourism brought in another $2.6 billion. That revenue, mostly spent locally, has a multiplier effect several times as much, or a contribution likely well over $10 billion a year from both sectors combined. The oil industry’s earnings largely leave the province, while total royalty revenues from 16 years of production offshore amount to less than one year’s revenue from seafood exports.

The conclusion is obvious: favouring the oil industry over the interests of our traditional industries makes no economic sense. It is a measure of corporate capture that the extractive industries receive the priority they do amongst our political elites.

My thesis: The long-run returns from investment in a restored fishery, reinvigorated agriculture, a better supported tourism sector, a strengthened boat- and ship-building sector, sustainable forestry, a growing marine-based high tech sector, and a commitment to shifting Nova Scotia to a renewable energy base (to name some of the obvious investment targets) would eclipse returns to further investment in extractive industries. It would also eliminate the catastrophic risks that come with the latter.

An economic strategy whose guiding principle is sustainability would be supported by a regulatory and research framework very different from the one we see today.

A regulatory regime designed for sustainability would place rebuilding and protecting renewable resource stocks ahead of other considerations. Sustainable yields, not maximizing short-term returns, would be the yardstick against which development proposals are judged. The impact on traditional renewable industries and on the communities they sustain would be a key factor in determining which developments proceed and which do not.

Restoring our fisheries is the low-hanging fruit

Let’s look at the potential in two sustainable food production sectors of Nova Scotia’s economy – the fishery and agriculture.

The disappearance of the inshore fishery (with the exception of shellfish and crustaceans) and the fish it depended on is one of the biggest ecological disasters in recent history. It should also be ranked as an economic fiasco.

Canada’s marine fish populations have declined by 55% since 1970. Canada has gone from being the seventh largest producer of wild fish by weight in the 1950s to twenty-first place today.

The collapse of the Northern cod fishery alone, and the subsequent moratorium, put 30,000 people out of work and devastated countless communities dependent on cod for centuries.

The causes of the collapse in the inshore fisheries are manifold:

- a federal Department of Fisheries bias towards corporate fishing,

- factory trawlers and advanced fish-finding technology,

- mismanagement of the resource,

- foreign and domestic over-fishing,

- a failure to listen to inshore fishermen,

- ignorance or suppression of science and, of course,

- political cowardice,

They all played a role.

We have yet to take the lessons to heart as we barrel ahead with the old model, avoiding our responsibility to conserve the resource and take the measures needed to sustain the catch.

Yet, if we want to strengthen the regional economy, build on our strengths, and guarantee a future to countless communities and the thousands dependent on the fishery for their jobs, then the biggest pay-off to investment is right here in traditional sectors.

Restoration of the East Coast fishery promises enormous economic and social benefits. Given that fact, it is extraordinary that it doesn’t appear to be a priority of either the federal or provincial government in Nova Scotia.

Little effort to date has been focused on rebuilding overfished stocks. The failure to reinvest is inexplicable and unforgivable. Fisheries experts have no doubt that rebuilding the fishery is doable!

The first step is to bring Canada’s federal Fisheries Act up to the global standard set by international agreements to which Canada is a party. They mandate countries to restore or maintain fish stocks at levels capable of producing maximum sustainable yields.

Canada’s new Fisheries Act (Bill C-68) recognizes the need to rebuild the fishery, but falls short of provisions common to the best legislation globally. Political cowardice and short-term thinking, and no small amount of corporate involvement in the fishery continue to doom our fish stocks.

Strengthening the Fisheries Act to require stocks to be rebuilt when they fall below an identified threshold is the first step in a sustainable economic strategy for renewable marine industries.

The benefits of such legislation are clear.

In the US, the amended Magnuson-Stevens Act required rebuilding plans for 44 overfished stocks more than a decade ago. By 2018 the all 44 overfished stocks had been restored

The economic impact? The rebuilding of US fish stocks has generated on average 50% more revenue than when those stocks were overfished!

The story from the EU is similar. The number of stocks with a total allowable catch designed to produce maximum sustainable yield has gone from 2 in 2007 to 53 in 2016. The cod has registered a return to health from a state of collapse in the North Sea, in Norway and the Barents Sea

Alas, the story in Canada is a tale of failure. Of 26 critically depleted fish stocks (stocks that are unsustainable at present levels of exploitation, or in danger of disappearance), only three have rebuilding plans in place.

This fact alone speaks to a lack of political commitment to sustaining a vital element in a robust coastal economy. It makes the irresponsible federal/provincial promotion of fossil fuel development in the Atlantic offshore all the more reprehensible.

Rebuilding the fishery is the real low-hanging fruit for a progressive economic development strategy in coastal Nova Scotia. It promises more jobs and a higher return to those in the industry.

A bonanza awaits Canada as a late-comer to the global effort to restore fisheries.

In any rebuilding effort, there remain thorny issues:

- how harvesting of additional stocks should be shared?

- How do we keep the primary benefit from going to large corporate entities at the expense of smaller inshore operators?

- How do we ensure a return to a healthy inshore fishery?

- How do we allow for specialty producers, hand-liners and such who serve first class products to local and luxury clientele?

These are matters for open debate in community forums. Still, debating the distribution of a much larger, sustainable harvest is a luxury we cannot yet enjoy. The missing ingredients remain political will and good management practices.

Don’t forget the knock-on effects of improved returns to the fishery – the high local “multiplier” effect of fishery income, strengthening the economic base in rural Nova Scotia, boosting the resilience of our communities, increasing their capacity to support essential social programs like health care and education, better municipal services, increased demand for locally built boats, and increased appeal to tourists who visit to enjoy our seafood, amongst other benefits.

Finally, the thought of putting that future at risk by reckless approval of offshore oil and gas exploration makes no sense at all.

The guiding principles for restoring the fishery – building on traditional knowledge and skills, precautionary exploitation, conservation, maintenance and sustainability, local involvement in all decisions, and maximizing local benefits apply to all renewable sectors.

Agriculture and food security

Let’s look at the potential in agriculture.

A leading Dutch bio-scientist has said that,

“The planet must produce more food in the next four decades than all the farmers in history have harvested over the past 8,000 years….If …(not)… a billion or more people may face starvation.”

Ernst van den Ends, Managing Director of Wageningen University of Research’s Plant Sciences Group. NG ibid. p93-4

The world faces a looming catastrophe.

A dismal fact that also represents an enormous opportunity for regions with sustainable agricultural potential. Nova Scotia is one of them.

While there are reasons to dismiss a strict comparison between Nova Scotia and the Netherlands not least their very different populations (Pop 17.08 million vs. 960,000) , consider the following facts:

- The Netherlands, averages 10 degrees latitude further north than our province, with only 74% the area, (Netherlands – 51-54 degrees north latitude, area 42,508 sq. Km.. Nova Scotia – 43-47 degrees north latitude, area 55,284 sq. Km.)

- Once considered “bereft of almost every resource long thought to be necessary for large-scale agriculture” (Nat. Geog. Spt. 2017), the Netherlands is, incredibly, the globe’s number two exporter of food, measured by value, after the United States, which has 270 times its land mass.

- Twenty years ago, the Dutch embraced sustainable agriculture under the rubric, “twice as much food using half as many resources”.

- Dutch farmers cut their use of water by up to 90%, almost eliminated chemical pesticide use in greenhouses, while poultry and livestock producers cut their use of antibiotics by up to 60%.

- Netherlands is the world’s top exporter of potatoes and onions and the second largest exporter of vegetables by value.

- More than a third of global trade in vegetable seeds originates in the Netherlands (no GMOs).

- The Netherlands is a world leader in aquaponics, which integrates raising fish and plants into a single system.

- The Netherlands success is underpinned by an unprecedented investment in university research facilities designed to bring the farm sector into the lab and vice versa.

Is it crazy to suggest that Nova Scotia, with significant, relatively inexpensive, high quality agricultural land, a highly educated population and quality research universities, has enormous potential to both feed itself and others?

We can do so through judicious investment in local talent, potentially creating hundreds, if not thousands, of additional jobs in food production and applied research. As the Ivany Commission pointed out, import substitution in the food industry could be a very significant contributor to a stronger and more independent provincial economy.

See also: Podcast: Organizing in small town Nova Scotia to stop offshore drilling

With a special thanks to our generous donors who make publication of the Nova Scotia Advocate possible.

Subscribe to the Nova Scotia Advocate weekly digest and never miss an article again. It’s free!

This article speaks the plain truth! It should be shared widely and determinedly! Never forget that it is the local focused economies that bring genuine prosperity and resilience, even through hard times like the gathering storm of climate crisis/ecosystems collapse/social instability upon us now. We can do it. Just do it!

Great article, some really good ideas here about making our farming number one. I live in Halifax but often have to go out of my way to buy NS produce. Just this week I wanted pears for a recipe and there were no NS pears in the Superstore I was in. Only one option from Canada, from Ontario. All the others were from outside the country. Why would our supermarkets have produce from outside the country when our local farmers are harvesting their crops?

In regards to the fishery and it’s return, we have to do a lot more to stop the pollution and raw sewage going straight into our waterways and oceans.

A remarkably well written and sourced article, Peter goes the extra mile in outlining the source of sustainability by identifying the need for policy and investment into our economic and renewable needs. Said another way, the “Whole Systems” view is the step back that allows us to focus on differentiating renewable resources from non-renewable resources, and we must treat them as such.

I would point out that Alaska has already set the stage for how we recognize non-renewable resource extraction, and hold the value for our current and future generations, with the establishment of the Alaska permanent fund, created at the onset of the vast oil wealth from Alaska’s North Slope.

Canada should be doing the same, at least 30% of the revenues from oil, gas, gold, and other non-renewable resources should be set aside into a Canadian Permanent Fund, where the funds would grow the economy, provide Canadians with annual dividends, and pay for ongoing social well-being, such as the National Health Care plan, Education, and other such economic growth aspects of our government.

let us not sell our heritage for a mess of mine tailings when the land could could support us for many generations. Instead teach the young – and the not so young – how to live in harmony with the earth. Greed is the disease of modern times and will be its death if not restrained!