Despite its incredible benefits to the oceans and to our fisheries, nearly one-third of seagrass worldwide has been lost in the past century alone. Here in Nova Scotia, we have an incredible opportunity to protect it.

June 8, 2021 – World Oceans Day

KJIPUKTUK (Halifax) – We have a treasure right in front of our doorstep that few people know about — eelgrass beds, a remarkable coastal ecosystem under the waves, just steps off the coast. Very few people know that eelgrass provides critically important ecosystem services, including supporting our fisheries, helping to prevent coastal and beach erosion, and storing carbon. The UN has even declared eelgrass meadows a “secret weapon” in the fight against climate change. Unfortunately, seagrass meadows are also one of the world’s most threatened ecosystems. It is estimated that the world loses up to 2 football fields worth of seagrass each hour. That’s the equivalent of 336 football fields each week.

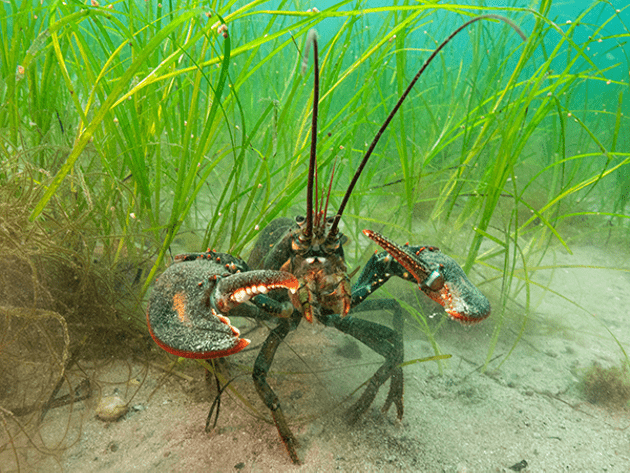

Around Nova Scotia, eelgrass beds are often found in sheltered shallow bays. Unlike seaweed, eelgrass is a type of seagrass, the only family of flowering plants that grow in the ocean. Of over 72 species worldwide, eelgrass (Zostera marina) is the most common in northern waters, growing as far north as Greenland. Most people have likely seen eelgrass washed up on the beach – long, grass-like blades, tangled with rockweed, shells, and other flotsam, and often overgrown with algae or little marine organisms.

Eelgrass is one of the world’s most effective ecosystems for storing carbon. Just one acre of eelgrass can store about 330 kg of carbon per year, which equals the amount of carbon emitted by a car travelling more than 6,000 km – greater than the distance from Halifax to Vancouver. About 2 acres of eelgrass can trap as much carbon as at least 10 to 40 hectares of forest. Like a forest, eelgrass also produces oxygen: one square meter can generate up to 10 litres of oxygen per day.

Eelgrass grows in dense beds that can even be seen from space. These beds also improve water quality, protect the coasts from erosion by reducing the power of waves, and provide important habitat for hundreds of different species. In the dense maze of the eelgrass blades, young lobster, crabs, herring, salmon, and some flatfish find their nursery habitats. These and many other species depend on the eelgrass to hide, spawn, and feed. This is why eelgrass is considered an ecologically significant biodiversity hotspot.

It is such important habitat for all kinds of marine species that DFO has declared eelgrass “essential fish habitat” due to its vital role for many fish stocks. Indeed, fishing has been called the “best argument for seagrass protection.” Scientists have discovered that seagrass beds provide important nursery habitats to over one-fifth of the world’s 25 largest fisheries, including many important fisheries in North America such as lobster, scallop, herring, and cod.

All these benefits, while their value is often hard to measure directly, add up. Eelgrass beds have been evaluated at over $20,000 per hectare, per year in terms of the services they provide, making them one of the most valuable ecosystems in the world.

Seagrass species, including eelgrass, are rapidly disappearing worldwide. Species in colder waters are suffering from rising water temperatures, disease, invasive species (such as the green crab), and deteriorating water quality. Eelgrass is very sensitive to run-off from land carrying too many nutrients. These are often from fertilizers or pesticides used on coastal properties or farmland along rivers. In many coastal areas, physical disturbances through boat anchoring, trawling, and dredging heavily damages or destroys the beds. These factors have contributed to the loss of nearly one-third of seagrass worldwide in the past century alone. Coastal developments, such as the proposed golf course at Owls Head Provincial Park on the Eastern Shore, put local eelgrass meadows at risk.

The consequences of losing this habitat are dire. Following a massive seagrass die-off in the 1930s and widespread destruction through scallop dredging, multiple scallop fisheries along the US East Coast (such as in Chesapeake Bay) collapsed. Several still have not recovered, almost 90 years later. And once the seagrass is gone, it will not come back easily. Countries like the United Kingdom are undertaking major restoration projects, trying to replant their lost seagrass meadows, but these projects take time and money and are far less effective than protecting the seagrass meadows we have.

Eelgrass is a secret treasure that belongs to all of us, to protect our coasts, supply our fisheries, and help fight climate change. Yet, across the province, citizens and scientists need to stand up to protect this and other important ecosystems from open-pen aquaculture, clear-cutting, gold mines, and unsustainable land developments.

One of the latest examples is the campaign to save Owls Head Provincial Park, a biodiverse coastal property on Nova Scotia’s Eastern Shore, now over 7,000-members strong. Owls Head Provincial Park has been a candidate for legal protection for over 45 years. In 2019, a whistleblower alerted the media that the government had secretly removed Owls Head Provincial Park from the provincial Our Parks and Protected Areas Plan. The government delisted Owls Head Provincial Park in a backroom deal for the benefit of a developer wishing to turn this parkland into golf courses. The government agreed to sell the nearly 700-acre property – with over 5 miles of coastline – for the bargain price of $216,000 ($306/acre).

Owls Head Provincial Park has a globally rare plant ecosystem, biodiverse wetlands, habitat for endangered species, and extensive, healthy eelgrass beds along the shore. The proposed development would mean “complete destruction of its ecology,” according to biologists who have done years of research at the site. A study that followed the development of a golf course along the coast in Florida determined that seagrass beds in adjacent areas diminished by more than 40%. The seagrass meadows were significantly affected by run-off from the golf course, which contained sediment, fertilizer, pesticides, and detectable amounts of mercury, lead, and arsenic.

The people of Nova Scotia now need to decide if they feel this is the appropriate place for such development. Our new premier campaigned on an environmental platform of climate change, biodiversity, and our network of protected areas. Yet, in the case of Owls Head Provincial Park, the Rankin government seems prepared to sacrifice all three, and that could be the beginning of a slippery slope.

Dr. Kristina Boerder

Dr. Kristina Boerder is a marine biologist from Dalhousie University. She and her team are conducting research on the terrestrial ecosystems and offshore eelgrass meadows in and around Owls Head Provincial Park.

This article was originally published on the Save Owls Head website, and it’s republished here with the group’s kind permission.

Related Reading

Protection of seagrasses key to building resilience to climate change, disasters – new UN report

United Nations Environment Programme: The Value of Seagrasses to the Environment and to People

The Power of Seagrass by Luke Hollomon, M.S.

Check out our new community calendar!

With a special thanks to our generous donors who make publication of the Nova Scotia Advocate possible.

Subscribe to the Nova Scotia Advocate weekly digest and never miss an article again. It’s free!