KJIPUKTUK (Halifax) – Black residents of the Town of Shelburne who live in the so-called South End neighborhood are worried about the effects of a nearby landfill on their health. They want the town to come to their support.

For 75 years the Shelburne Town Dump received industrial, medical and residential waste not just from the town, but also from Lockeport and all of eastern Shelburne County. Waste came from from households, a former naval base, a hospital, and an industrial park.

In the early nineties the landfill as such was closed, but it continued to be used as a transfer station for things like fridges, stoves, and empty oil barrels. Enforcement was lax.

Now residents worry about the effect of landfill contaminants on their health.

“We all have the same feelings and fears about what we were exposed to when we grew up, the many deaths from cancer we experience, the exceptionally high number of men that passed away before they turned seventy,” says Louise Delisle.

Delisle is one of the residents who joined the South End Environmental Injustice Society (SEED) to give the community a voice and raise the profile of its concerns.

“We have become a community of widows. Our parents lived it, we lived it, and now our children and our grandchildren are still being exposed to that landfill,” she says.

“The community now is mostly women. There are very few men left.”

For decades South End residents lived with the smoke from the waste being burned there, rats, and most of all, fears that the dump was contaminating their dug wells and affecting their health.

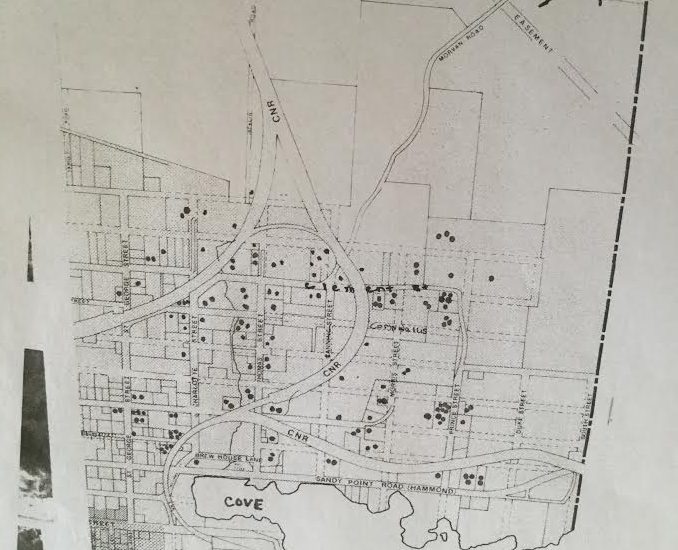

The two closest homes are within 250 feet, many more are within 500 feet. The neigbourhood is on a boggy downward slope from the landfill. Three brooks descend from the dump into Shelburne Harbour, crossing many South End properties.

“You know something isn’t right when you have people drive by your house in hazmat suits (protective clothing) to go to the dump and drop off their containers of whatever.”

“We lived it, and we talked about it every day. We breathed it. You couldn’t open your windows, you couldn’t breathe,” says Delisle.

“You know something isn’t right when you have people drive by your house in hazmat suits (protective clothing) to go to the dump and drop off their containers of whatever. And a few days later there would be a fire, and we don’t know what it was they dumped,” Delisle says.

Janet O’Connell, another member of the SEED group, has similar memories.

“People would dump animal parts. When the hospital dumped something there always was a fire. They always tried to burn whatever they dumped there. The fire would get underneath, and it would burn underground,” says O’Connell.

About ten years ago Delisle was involved in a study looking at health-related issues facing Black women in rural Nova Scotia. At that time she interviewed the African Nova Scotian women who lived in her town. The dump was the number one concern the women raised, she says.

“The community now is mostly women left over. There are very few men left. They died of cancer. I highly doubt that there will be similar numbers in the downtown or in the North End,” says Delisle. “And 99.9% of the women who are ill blame it on the dump.”

“The dump has contributed to not just cancer, but also affects our mental health, the stress of losing your loved ones, trying to care for your family while your environment is contaminated. And having to deal with the stigma of where you live, not being able to put your clothes on the wash line. The racist remarks behind that,” Delisle says.

“We were conditioned not to complain”

Dr. Ingrid Waldron’s ENRICH project has long made the case that a disproportionate number of landfills, waste sites, and other environmental hazards are located close to African Nova Scotian and Mi’kmaw communities.

What these racialized communities have in common is a lack of organization and political power. Rather than trying to remedy that, government tends to exploit that weakness.

It’s called environmental racism, a system and structure in Canadian society that privileges white people in terms of where environmental hazards are located.

“These were people who were afraid of losing their job, who had very little. People who were afraid of causing any kind of problem.”

Delisle and O’Connell’s experience is in many ways a showcase of how such white privilege manifests, why the dump is where it is, and why complaints by residents up until very recently were easily ignored.

Residents had no choice but to accept whatever the town decided. It’s not as if residents could pack up and leave, says Delisle.

“Our homes were modest, although we worked and built and did whatever we had to. The men worked in the town and couldn’t afford to live anywhere else,” she says.

As well, it was a community that was not in a position to raise objections.

“These were people who were afraid of losing their job, who had very little. People who were afraid of causing any kind of problem,” O’Connell says.

“When you think about the black community, when you think about us, my parents and my grandparents, they were people who, I guess because of slavery, never said anything, never voiced their opinion to people who could make a change. We were conditioned not to do that,” Delisle says.

“For our children and grandchildren”

On November 16 Town council decided to permanently close the dump.

A total clean-up and removal of contaminants remains a key demand of SEED. “We’re still exposed, all that stuff is still underneath,” says O’Connell.

“And we want the community compensated in some way for the racism it experienced, and the illnesses and cancer that come with the contaminants we have been exposed to,” Delisle says.

The members of SEED are also calling for access to town water. So far all the Town of Shelburne has offered is to extend the water main into the community, but only if the group can raise the money to pay for it.

That’s not good enough for the group. “We have a basic right to clean water. People shouldn’t have to worry about paying for that. We have lost enough,” says Delisle.

There may be opportunities to work with the Province and the Federal government to tackle cleanups and access to town water, the group believes. To explore these opportunities, the group wants the town to take on more of a lead role. So far, this has not happened, SEED members say.

We asked Karen Mattatall, the mayor of Shelburne, to respond. Mattatall declined an interview and her emailed response disregarded most of our questions.

“As for drinking water, the Town supports all residents having access to clean and safe drinking water and are more than willing to assist residents with water testing when necessary to ensure their drinking water is safe,” wrote Mattatall.

Meanwhile, SEED is working with scientists associated with the ENRICH project to better understand the risks the dump poses to groundwater quality. Expect a follow-up story in the Nova Scotia Advocate on this aspect of SEED’s quest for clarity in the next week or so.

As well, the group is focusing on recording video and audio stories from current and former South End residents. Collecting health-related data is also a priority, for obvious reasons.

Like it or not, and with or without the town’s help, the group will get their issues addressed, members tell the Nova Scotia Advocate.

“For our children and grandchildren, and for generations to come, we need to know that something like this will never happen again,” says O’Connell.

If you have a bit of money to spare, please support the Nova Scotia Advocate. It will allow us to continue to cover issues such as poverty, racism, exclusion, workers’ rights and the environment in Nova Scotia.

Hmm. Railway tracks and a foul landfill. Africville revisited.

Thank you for publishing this awesome article. I’m a long time reader but I’ve never been compelled

to leave a comment. I subscribed to your blog and shared this on my Facebook.

Thanks again for a great post!