KJIPUKTUK (Halifax) – For part five of our series on the social determinants of health, I’ll focus on social exclusion among marginalized communities. The social determinants of health are the living conditions people experience that impact whether they stay healthy or become sick, things like poverty, housing, education and the kind of job you have.

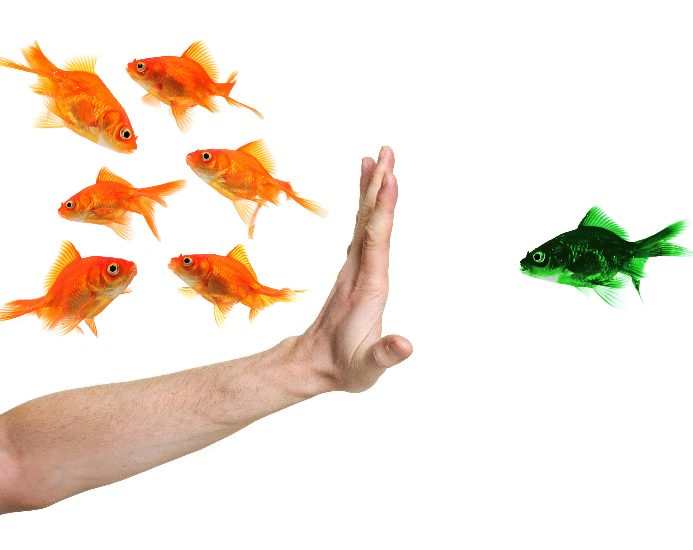

Social exclusion means being denied the opportunity to participate in various aspects of life that others take for granted. In Canada, among the people most vulnerable to social exclusion are indigenous peoples, people of colour, recent immigrants, women, people with disabilities, and people who live in deep poverty. There are other groups as well, and people who live on the intersections of these groups are affected even more.

There are four types of social exclusion.

Denial of participation in civic affairs often happens because of legal sanctions and other structural barriers. Immigrants and non-status Canadians often cannot participate in certain activities because of various laws. Recent immigrants often have to work jobs below their qualifications due to some rather archaic regulations and procedures.

Denial of social goods, including health care, education, housing, income security, and language services is very common among marginalized communities. They are more likely to live in poverty because of lower income levels, lack of affordable housing, and poor access to medical and other services.

Exclusion from social production is when marginalized groups cannot partake in recreational activities, clubs, cultural events, and other social activities. This is often because they lack the necessary financial resources to take part in these activities.

Economic exclusion is when people cannot find well-paying jobs or access other economic resources. This kind of social exclusion crosses boundaries between all types of marginalized communities.

So as you see, social exclusion takes many forms. Not only is it a social determinant of health on its own, it has a substantial impact on other social determinants of health.

There are signs of progress being made in Nova Scotia to address social exclusion, although there is still a long way to go.

One such sign has been the introduction of Bill 59, the Accessibility Act, to ensure Nova Scotia is more accessible to disabled people. After criticism from several disability rights activists, it was redrafted and eventually passed after the Law Amendments Committee received a number of submissions. This was an important effort on the part of our government to listen to the people who are affected by their policy decisions.

Racism is also linked to social exclusion. The controversy around police street checks, or carding, has been one issue the African-Nova Scotian community has brought to the forefront recently. Black people are disproportionately targeted by this practice. However, there has been no substantial discussion on carding by our provincial or municipal representatives, and the Halifax Regional Police have said they won’t be suspending the practice any time soon.

These issues are far from fully addressed, and while there is some discussion in the mainstream media, some people believe the progress isn’t much to write home about.

Marginalized groups typically have little to no power to influence public policy issues that affect them. The disabled community was able to advocate for changes to Bill 59. However, there are still lots of struggles ahead to create public policy that adequately supports our most marginalized communities and reduces social exclusion.

Alex Kronstein is an Autistic adult and host of the podcast The NeurodiveCast. He is passionate about disability rights, social justice issues, and filmmaking. Follow Alex on Twitter.

If you can, please support the Nova Scotia Advocate so that it can continue to cover issues such as poverty, racism, exclusion, workers’ rights and the environment in Nova Scotia. A pay wall is not an option since it would exclude many readers who don’t have any disposable income at all. We rely entirely on one-time donations and a tiny but mighty group of kindhearted monthly sustainers.