KJIPUKTUK (Halifax) – Disability arts, it sounds so intriguing, but what is it, exactly? Simply put, one could say disability arts is about how being a disabled artist influences what you create.

Deaf and disability arts, as defined by the Canada Council for the Arts, “are diverse artistic practices in which being deaf, having a disability or living with mental illness are central to the exploration of narrative, form and/or aesthetics. This work carries a high degree of innovation and breaks traditional or dominant artistic conventions to bring distinct perspectives and ways of being into the arts ecology, shifting perceptions and understandings of human diversity.”

Canada has the oldest history of disability arts production in the world, but not all regions of Canada have a strong disability arts scene. The Atlantic provinces have perhaps the least developed disability arts scene in Canada.

To understand more about what disability art is, it’s important to understand the meaning of disability culture, deaf culture, and mad culture.

Disability culture advances the idea that disability is a natural part of the human experience, inverts the shame of disability into pride, and most importantly, rejects the dominant belief that people with disabilities need to be “fixed”.

Deaf culture is the set of social beliefs, behaviors, art, literary traditions, history and values influenced by deafness and that use visual or sign languages as the main method of communication.

“Mad” is a social and political identity by those labeled as mentally ill or having mental health issues. Movements such as Mad Pride, as opposed to focusing on awareness or coping with stigma, instead center on expressing the unique ways people experience the world in terms of making meaning, developing communities, and creating culture. Mad culture affirms mad identities and develops and empowers mad communities, and also challenges discrimination and participates in mad history.

So now that we have a basic definition of disability, deaf, and mad cultures, let’s take a look at what disability arts is.

Colin Barnes, Emeritus Professor of Disability Studies at the University of Leeds, defines disability art as “not simply about disabled people obtaining access to the mainstream of artistic consumption and production. It is the development of shared cultural meanings and collective expression of the experience of disability and struggle. This entails using art to expose the discrimination and prejudice disabled people face and to generate group consciousness and solidarity.”

According to Michele Decottignies, Chair of the Deaf, Disability & Mad Arts Alliance of Canada, there are three distinct practices of disability art in Canada: art & disability, disability-inclusive art, and disability-identified art.

Art & disability is simply traditional art forms practiced by artists with disabilities, without regard for disability politics, culture or pride.

Disability-inclusive art is when disabled people receive accommodations that allow non-traditional artists to adapt to traditional aesthetics.

Disability-identified art is not simply created by artists with disabilities; it embraces and promotes disability politics, culture and pride. It prioritizes resistance, affirmation, and inversion.

Resistance is often applied in artistic content, when disability stereotypes and biases are challenged and reframed, and disability is celebrated as a kind of diversity instead of shame.

Affirmation is typically applied in artistic form, when any impairments are used as the main artistic properties in the artist’s work, and impairment itself is positioned as a source of artistic enrichment.

Inversion is usually applied in the artistic process, through repurposing as opposed to adaptation. As visual arts curators Syrus Marcus Ware and Elizabeth Sweeney have said, “All adaption allows is for inclusion, period. Repurposing requires the altering of something so that it takes on an entirely new function. For politicized, diverse artists, repurposing is not just an aesthetic preference but a necessary act of survival: by reshaping and reinventing art forms, we’re redefining reality and representing a more complete picture of Canadian society.”

As Decottignies herself acknowledges, the practice of disability arts is not quite this rigid. There is considerable overlap between the three practices, and many people who practice disability arts produce and engage in all of them.

As mentioned at the beginning of this article, Canada has the oldest history of disability arts production in the world, but Atlantic Canada’s disability arts scene is seriously underdeveloped. In Part 2, I will provide some examples of disability art from elsewhere in Canada and the world that could hopefully provide inspiration for what a strong Atlantic Canadian disability arts scene could look like.

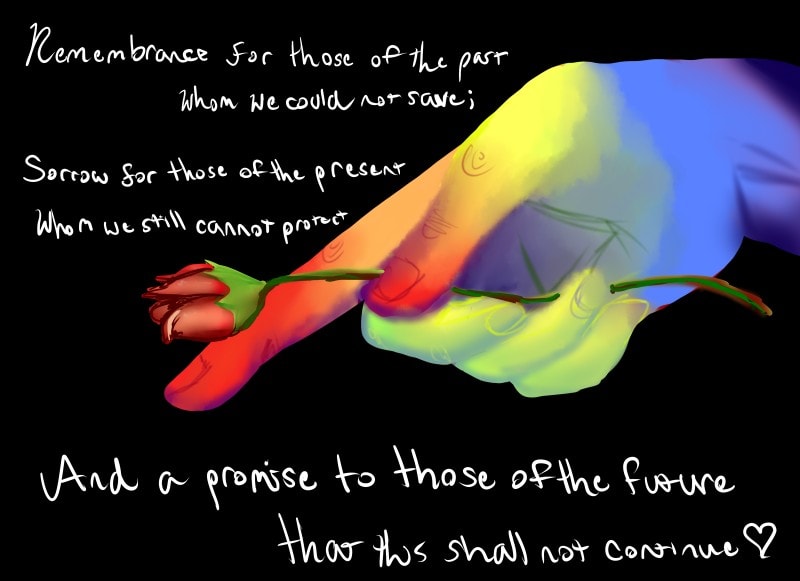

About the art

Jennifer Partin is an Autistic artist and university student from The Colony, Texas. She recently drew this while reading The ME Book by Ivar Lovaas, which is essentially the ABA (Applied Behaviour Analysis) handbook, and liveblogging it on her Facebook page.

ABA is the most common therapy for Autistic children, but it is universally despised by the Autistic community, as many Autistic adults have written about their experiences with ABA and how they have PTSD from going through it as children. A great many Autistic activists say that ABA as developed by Lovaas also seeps into today’s “play-based” autism therapies. Lovaas was also a key figure in the development of what’s known today as “Gay Conversion Therapy”.

The video is a collage of images from the book “Christmas in Purgatory” by Burton Blatt, set to the song “The Moon Come Up” written by Gregory Hoskins and performed by Kindred Spirits. Norman Kunc was born with cerebral palsy, and doctors recommended that he be placed in an institution. His parents refused, but Norman has always wondered what his life would have been like if his parents had taken the doctors’ advice.

Norman and his wife Emma Van der Klift are two of the most well-known disability rights activists in Canada. They operate Conversations That Matter, an online values training platform with over 80 video segments of conversations with well-respected trainers, scholars and advocates in the field of disability rights. They live in New Westminster, British Columbia.

Further reading:

The art of deaf, disability and mad arts, presentation by Michele Decottignies

Disability Arts and Equity in Canada, Michelle Decottignies

Alex Kronstein is an autistic adult and host of the podcast The NeurodiveCast. He is passionate about disability rights, social justice issues, and filmmaking. Follow Alex on Twitter.

If you can, please support the Nova Scotia Advocate so that it can continue to cover issues such as poverty, racism, exclusion, workers’ rights and the environment in Nova Scotia. A pay wall is not an option since it would exclude many readers who don’t have any disposable income at all. We rely entirely on one-time donations and a tiny but mighty group of kindhearted monthly sustainers.