KJIPUKTUK (Halifax) – Last night there was yet another meeting on water quality issues in the Harrietsfield and Williamswood area. This time part of the focus was on the Harrietsfield Elementary School, where kids are advised not to drink the tap water because of a high uranium content.

To say that the 40 or so residents at last night’s meeting were concerned is an understatement.

The area has known of its water problem for decades now.

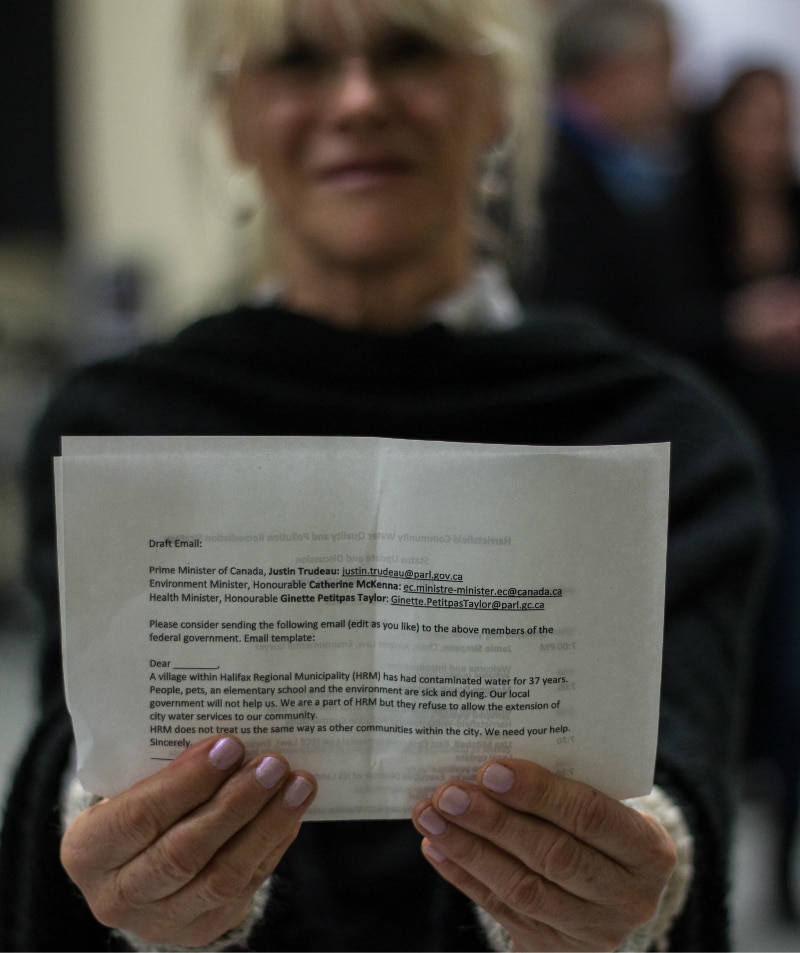

Citing government reports dating back to 1980, Harrietsfield’s tireless community advocate Marlene Brown discussed the history of high amounts of uranium detected in the region’s groundwater, making the water in people’s wells unsafe to drink.

“In 1981 the Nova Scotia Department of Health carried out an extensive sampling program which determined that 107 wells in the Harrietsfield/Williamswood area exceeded the 0.02mg/1 limit (of uranium),” it says in the Harrietsfield Williamswood Pollution Control Study, which was published by the municipality in 1987.

“30 years ago, they did this study. A lot of these problems are probably fixed, but more than likely a lot of them are not,” Brown said.

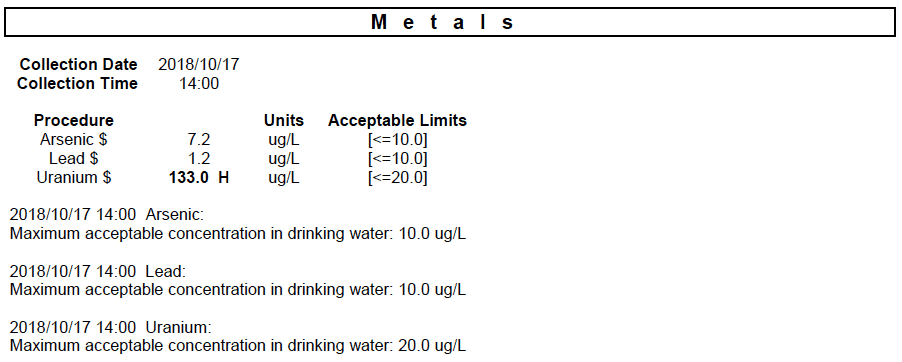

Uranium concentration in drinking water seven times over the limit at Harrietsfield Elementary School

One problem that has not been dealt with has to do with the water quality at Harrietsfield Elementary School. The school is 500 metres away from a contaminated site which was once home to frequent illegal dumping, illegal waste disposal practices and that still houses a containment cell with 120,000 tonnes of toxic waste inside. The cell was improperly built, and ended up leaking chemical contaminants into the ground and groundwater.

Concerned about the water quality, Brown submitted a water sample from the school to be tested and analyzed by the Environmental Services division at the Nova Scotia Health Authority.

“Today I got the results from our school. The uranium is 133, the arsenic is 7” she says at the meeting. The maximum concentration of uranium in drinking water is 20 micrograms per litre, according to the Canadian Drinking Water Guidelines, meaning that the school’s concentration of uranium, 133 micrograms per litre, is almost seven times over the accepted limit.

Dalhousie professor Judith Guernsey, an environmental epidemiologist specializing in community health, has initiated an independently funded health impact study on water quality in Harrietsfield. In an email she sent after the meeting she wrote that drinking water with a concentration of uranium of 133 micrograms per litre is linked to kidney damage.

“Radon gas has also been shown to be elevated in homes where drinking water contains higher uranium concentrations. Radon gas exposure has been shown to be associated with lung cancer,” Guernsey wrote.

Guernsey notes that “clinical studies of the health effects of uranium exposures that involved members of the Harrietsfield community in the 1980’s are amongst the most cited of publications about the chronic effects of elevated uranium exposure worldwide.”

As well, citing a recent study, Guernsey said that when arsenic concentrations are more than 5 micrograms per litre, the risk of bladder cancer is 18% higher and the risk of kidney cancer is 14% higher than when concentrations are from 0-2 micrograms per litre.

During her presentation, Brown expressed deep concern for the health of those at the school.

“I found out in June, four little girls were filling up their water bottles in the bathroom sinks. So any parents, please let your children know—do not fill up their water bottles in the sink,” Brown says, showing images of caution signs that have been put up in the school’s bathrooms.

“We’re talking about children five to eleven, maybe. I’m sorry but a five and a six-year-old cannot read chemical contamination notices, and these are above the sinks, where the water is still running with all this contamination,” she says.

Something was always off with the water

Valerie Gallant, a resident of Williamswood and former teacher at Harrietsfield Elementary, told the Nova Scotia Advocate that when she sees photos of the caution signs on the walls of the school, it terrifies her.

When Gallant worked at the school from 1975 to 2008, she does not recall seeing any signs, but she does recall telling the children not to drink the water from the fountains.

“We did tell the children when they first realized that the water was not going to be potable (in 1980), and they brought in water and they drank out of paper cups. That’s what they had, little paper cups,” Gallant says.

She also recalls someone from the Department of Environment coming to take water samples, but “he never engaged with us and talked to us about what he was actually doing. He would just take his water samples and then he would go,” she says.

“Other than that, we instructed the kids to use the bottled water, which was at times really inconvenient because the bottles would empty, the janitor wouldn’t be really diligent sometimes at replacing them, they were huge and heavy for female staff, you know, to tip upside down.”

Plus, the small Dixie cups given to the children held very small amounts of water, making it disruptive for teachers when their students were thirsty.

“You have little ones that are thirsty coming from gym, so they want to get multiple cups of water,” she said. “It didn’t work very well.”

From the beginning, Gallant sensed something was “off” with the water at the school, so she never drank it. Thanks to frequent testing, she knows that her well water is safe to drink, and she always brought her own water to work with her.

“If I didn’t have my water with me, I didn’t drink. And I have no health issues,” she says.

Gallant mentioned that several teachers and staff left the school for health problems, such as autoimmune issues, and respiratory issues stemming from the poor air quality in the building. She also recalls children having frequent “severe nosebleeds” and noticed patterns of behavioural issues among children from Harrietsfield, particularly in the areas where they first detected uranium.

“It’s not just about the water, it’s about us”

According to Brendan Maguire, the MLA for Halifax Atlantic who attended the meeting, the principal of the school said that the water is regularly tested, students are advised not to drink from the taps and instructed to use bottled water.

After the presentations, community members were given the opportunity to ask questions. Many expressed concern for the health of their grandchildren who are currently attending Harrietsfield Elementary School.

Mark Welsh, a long-time resident of Harrietsfield, said the biggest thing he senses is “a lack of urgency” with regards to how the government is dealing with the issue of the contaminated site, but also the community’s lack of access to safe drinking water. As Brown points out, they have been relying on the taps at St. Paul’s Church to fill up bottles to live off of for five years now.

Others tried to appeal to Maguire and district councilor Stephen Adams to feel empathy for the people forced to live with the contaminated water, especially for those who are sick and struggling every single day.

“It’s not just about the water, it’s about us,” Angela Welsh says. “It’s very serious. It’s life or death for some people.”

See also: Drinking water fears confirmed at angry Harrietsfield community meeting

With a special thanks to our generous donors who make it possible to pay our writers for their important stories.

Subscribe to the Nova Scotia Advocate weekly digest and never miss an article again.