KJIPUKTUK (Halifax) – Many Nova Scotians have never seen a Black Ash – it’s a modest tree, relegated to bogs and swamps, places we often avoid. And when we think of endangered species, it’s tigers, eagles, sharks that come to mind. Trees? Not so much.

But now that the Emerald Ash Borer has arrived on the east coast, the Black Ash is in danger of disappearing entirely in Nova Scotia – and for some, this tree is exceptionally precious.

There’s a connection between the Mi’kmaq people, and the Black Ash. A connection that extends far beyond lip-service, into the realm of serious, intensive, conservation – it’s the reason Mi’kmawey Forestry, based in Truro, has been working to conserve the tree they call wisqoq (roughly pronounced wiss-koh) for years.

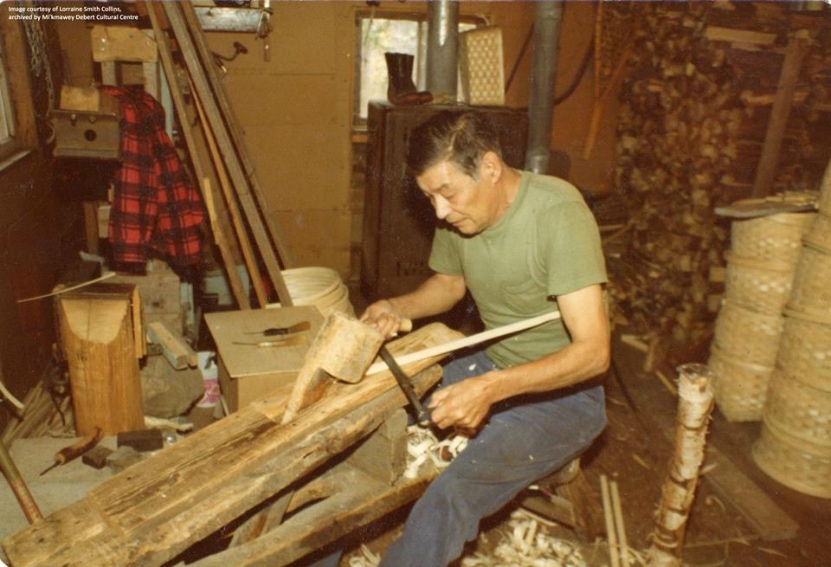

Della Maguire, daughter of world-renowned basket-makers Rita and Abe Smith, knows this connection well.

For centuries, Maguire tells me, her people – the Mi’kmaq – were migratory. Movement was a necessity, a way of letting the land around them regrow, replenish. Everything they needed was carried. And much of what they carried, was carried in baskets.

The Mi’kmaq often refer to Black Ash wood as white gold: It’s the perfect material for basket-making.

Everybody who uses it,” Maguire says, “knows it’s a shapeshifter.” She talks reverently about the texture of the wood, it’s shape, it’s personality. “When you touch it,” she says, “it gives you a feeling that you just want to do something nice with it.”

Now, the Mi’kmaq art of basket-making is in trouble. In early September, the Emerald Ash borer, an invasive beetle from Asia, was found for the first time in our province – in a small park in Bedford. The history of this pest paints a grim picture: when the beetle sweeps through an area, virtually all ash trees die within 10 years.

In Nova Scotia, the clock is ticking.

In what little time they have left, Mi’kmawey Forestry is searching for the remnants of Nova Scotia’s Black Ash, documenting trees and collecting seeds. Cody Chapman, who heads the organization’s Black Ash Recovery Project, spent most of his summer and early fall in the forest. On the project website, wisqoq.ca, it accepts tips from those who recognize the tree, on their property, for example, or while hiking. And traditional knowledge is vital, Chapman tells me – many of his leads come directly from basket-makers.

Walking in the forest, Chapman sees the power of the Black Ash firsthand: the roots shelter salamanders and frogs, while deer and moose forage on leaves. And often, he finds the Black Ash sharing these landscapes with other species-at-risk – including, in one instance, the endangered mainland moose.

But only about 1000 Black Ash trees remain in the province – and that isn’t even the worst part. Many of the trees Chapman finds are stunted, warped, and isolated. And too often, a search ends in disappointment: nothing but “rotting logs,” he recalls, “where the trees used to be.” Healthy trees are rare; stands of healthy trees – a requirement for natural fertilization – are rarer still.

“The vast majority [of Black Ash],” Chapman tells me, “are not expected to produce seed.”

The situation is bleak. But still, the organization isn’t giving up. Everything Mi’kmawey Forestry does is imbued with the spirit of Netukulimk: leaving something for the future generations. And so the organization maintains plantations in Nova Scotia, growing black ash seedlings around Mi’kmaq communities.

The seedlings are doing well so far – aside from some trouble with deer – and the planting continues steadily. It’s a much-needed source of hope. The seedlings will be too young when the Emerald Ash Borer arrives, and eventually, the trees can be harvested for future basket-makers.

Perhaps one of their largest successes is in education and outreach. Indeed, their website is a hub of identification tips, history, and news. And Mi’kmawey Forestry runs planting workshops and basket-making classes, often, for youth. In a video of one workshop at L’nu Sipuk Kina’muokuom School in West Hants, child educator Greg Marr sums it up: “that’s a teachable moment.”

Despite these efforts, soon basket-makers like Maguire will have to stop working with Black Ash. The wood is simply becoming too rare. But while Maguire is worried about her art-form, she remains steadfast: “basket-making – in some form – will continue.”

Her culture, she reminds me, has been threatened before.

“At one point,” she says, “we weren’t even allowed to have our ceremonies.” And so now, she remains optimistic. And when she looks to the future of basket-weaving? “I can see my great-great-granddaughter,” she says.

See also: Weekend video: Ursula Johnson, multidisciplinary Mi’kmaq artist

With a special thanks to our generous donors who make it all possible.

Subscribe to the Nova Scotia Advocate weekly digest and never miss an article again.

Pingback: Canadian History Roundup – Weeks of December 16, 23, and 30, 2018 and January 6, 2019 | Unwritten Histories