May First, international working class day, is the 100th anniversary of the Halifax General Strike of 1919 against war profiteering and super-exploitation of the construction trades in the wake of the Halifax Explosion of 6 December 1917.

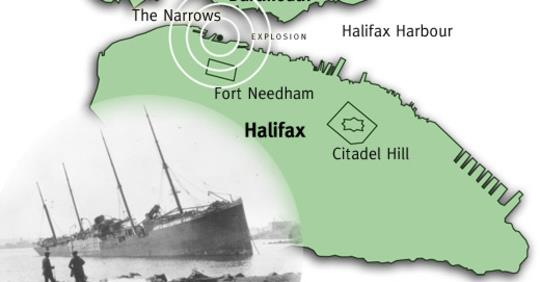

As a result, according to the understated official figures, 1,963 innocent residents of the city were killed, another 9,000 injured and 199 blinded – comprising more than one fifth of a total population of less than 50,000 – of whom 5,000 were soldiers and sailors, not including those convalescing in military hospitals from wounds suffered in Europe. Between 20,000 and 25,000 Haligonians were left homeless and destitute, including ten thousand children. It was the largest explosion in history before the infamous devastation of Hiroshima and Nagasaki by US atomic bombs in 1945.

A wall of silence: The resistance of the working class

The casual link between the disaster and the exploitation of the working class in the past and its impoverishment and resistance is denied. The working people of Nova Scotia have a long and glorious history of struggle to affirm their rights and the rights of everyone else. In the aftermath of the explosion, they resisted all attempts to ghettoize and marginalize them still further.

Under the pretext of dealing with the consequences of the Explosion, migrant, unskilled labour including Chinese coolies to replace the fallen longshoremen were recruited by the rich to keep Halifax functioning as a war port and to drive down wages, split the workers’ solidarity and break down the closed union shop. In February 1918 an Ontario labour paper, the Industrial Banner, referred to a group of Chinese labourers who had frozen to death enroute to Halifax and criticized the injustice of employing foreign labour when “Hardly a day passes but news comes of men and women being notified that their services are no longer required.”

The Halifax workers rose against the injustices, urban land grabs and profiteering from the misery prevailing after the Explosion by the unscrupulous men of property, culminating in a general strike of over 1,100 building trades workers launched on May Day, 1919 – the largest strike in the history of Halifax. Along with being the international day of the workers, May 1st was the traditional date for establishing new wage rates in Halifax.

Events in Halifax in 1919 and 1920 must be seen within the context of both regional, national and international working-class activity. Between 1916 and 1925 the Maritimes experienced unparalleled levels of strike activity. Economic militancy often translated into political action. Miners in Cape Breton, Cumberland, and Pictou counties, steelworkers in Sydney, and industrial workers in Amherst and New Glasgow participated in the upsurge of radicalism seen across the country.

This workplace militance was accompanied by a political awakening as labour, inspired by the example of the Bolshevik Revolution in Russia and similar initiatives in Europe at the end of World War I, broadened its activity beyond a traditional alliance with the Liberal party into an independent third party aimed at capturing power at the municipal and provincial levels.

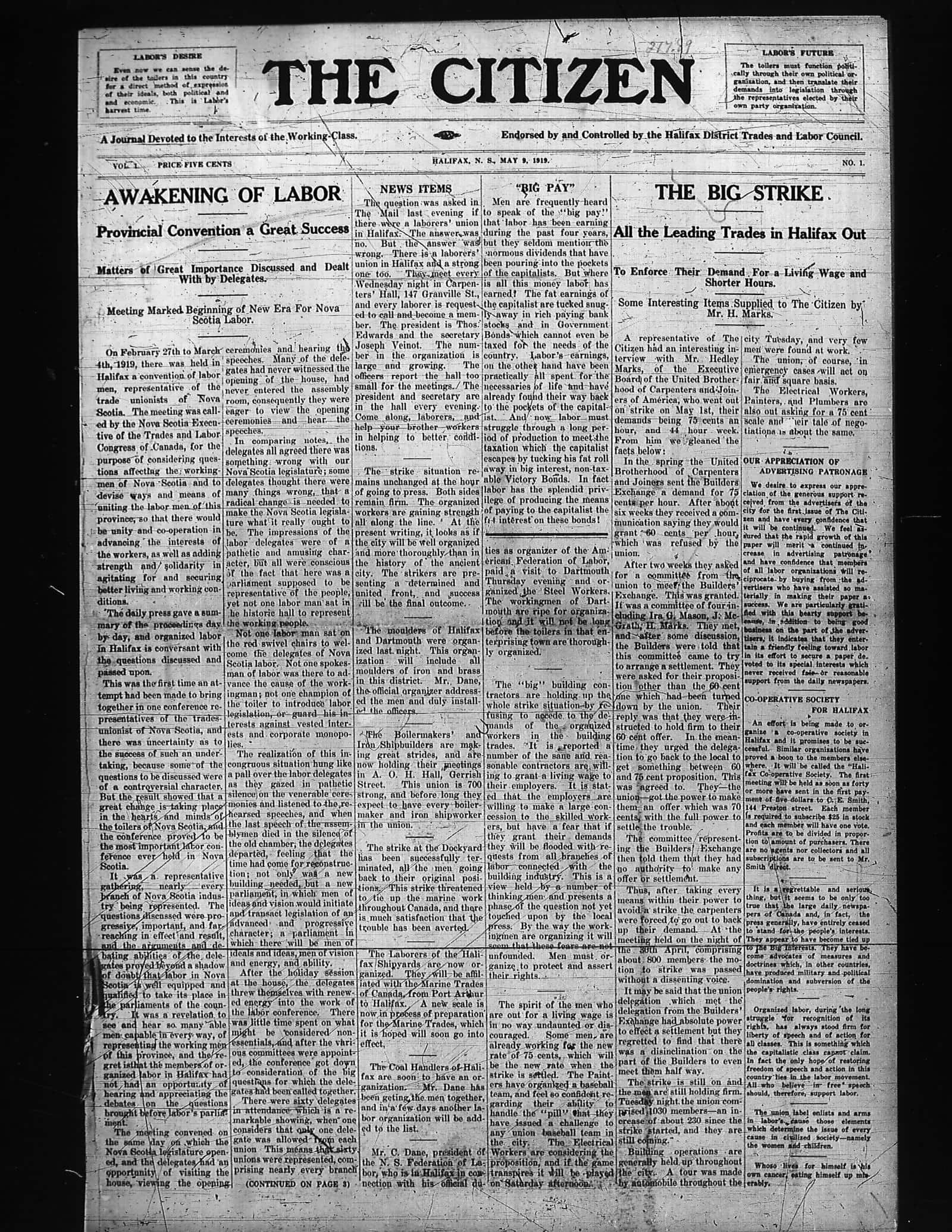

In parallel, on May 9, 1919, under the auspices of the Halifax Trades and Labour Council, Halifax workers begin publishing a weekly newspaper, significantly named The Citizen, capable of “presenting labour’s case to the public.

The Halifax Labour Party was revived by the Halifax Trades & Labour Council, inviting all “workers, whether organized or unorganized, mental or manual regardless of race, sex, creed or vocation.”

Information about the strike is suppressed by virtually every history of the Halifax Explosion, a consequence of Canada’s participation of the imperialist world war of 1914-1918 and the organization of Halifax as a war port in the service of the Anglo-American big powers, from which the Canadian bourgeoisie reaped enormous profits.

On May First, discouraged by post-war inflation and unemployment, Winnipeg’s metal and building workers went on strike, demanding higher wages. Winnipeg’s building trade workers walked out to gain better wages and hours. They were joined by iron workers who were fighting for company recognition of their union, the Metal Trades Council.

On May 15, with the overwhelming support of its 12,000 members, the Winnipeg Labour Council called a general strike. Thirty thousand union and non-union people walk off the job. Sympathy strikes were organized in Edmonton and Calgary in support of the Winnipeg General Strike.

On May 20, the locally organized industrial union, the Amherst Federation of Labour, calls “a general strike” of organized labour in that town, partly in sympathy with the workers of the Canadian Car and Foundry Company who had failed to achieve parity with the Montreal branch, and partly to back the demands for an eight-hour day, union recognition, and improved working conditions in individual plants. With two exceptions, the strike included workers of all the major industries of the town: foundaries, engineering works, textile mills, she, luggage, and wood-working factories, and even the local garage. (Reilly, Nolan. “The General Strike in Amherst, Nova Scotia, 1919”. Article in Acadiensis, Vol.IX, No.2, Spring 1980, pp. 56-77)

Also in May, more than 15,000 paper-mill workers in Canada and the US, who produced 60 per cent of all newsprint, struck against a thirty per cent wage cut.

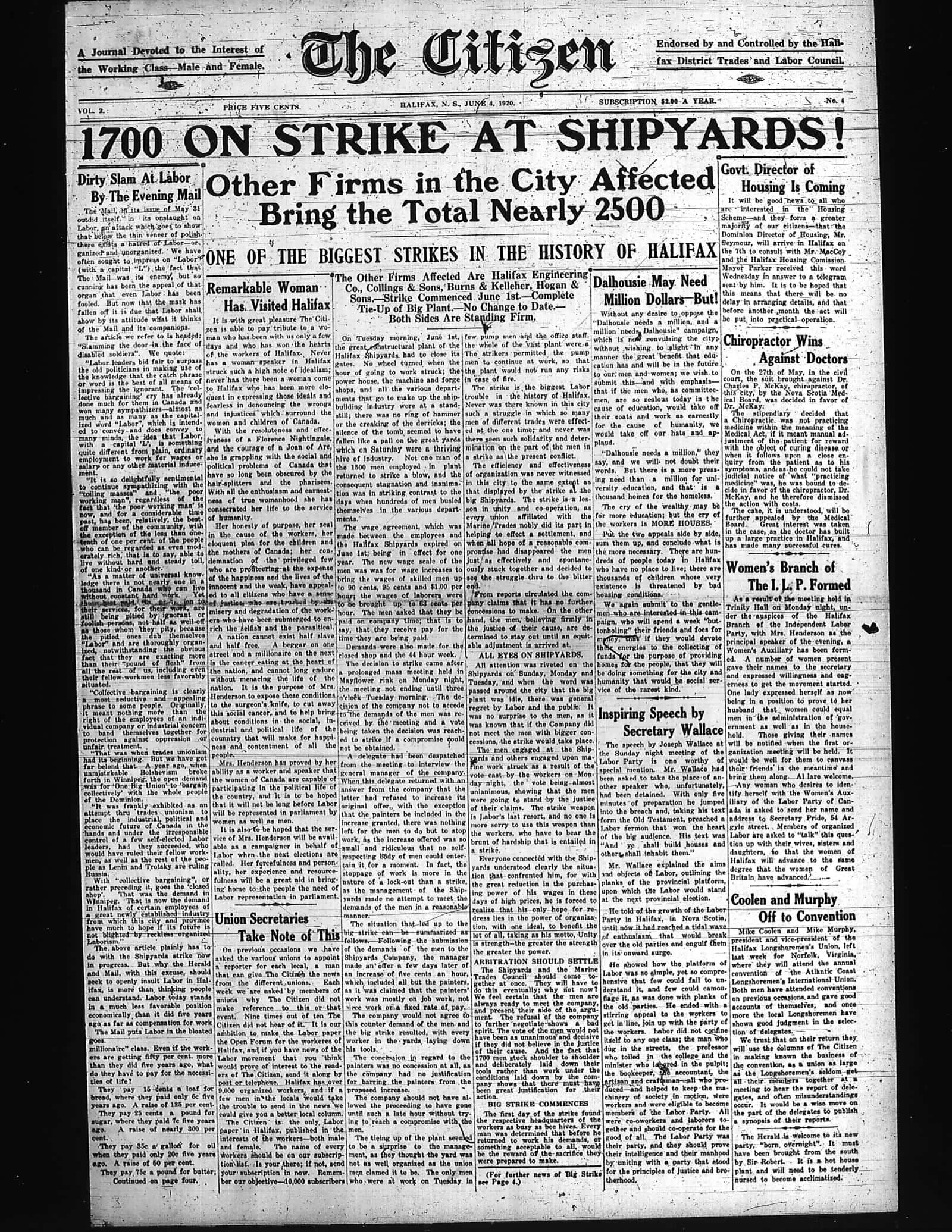

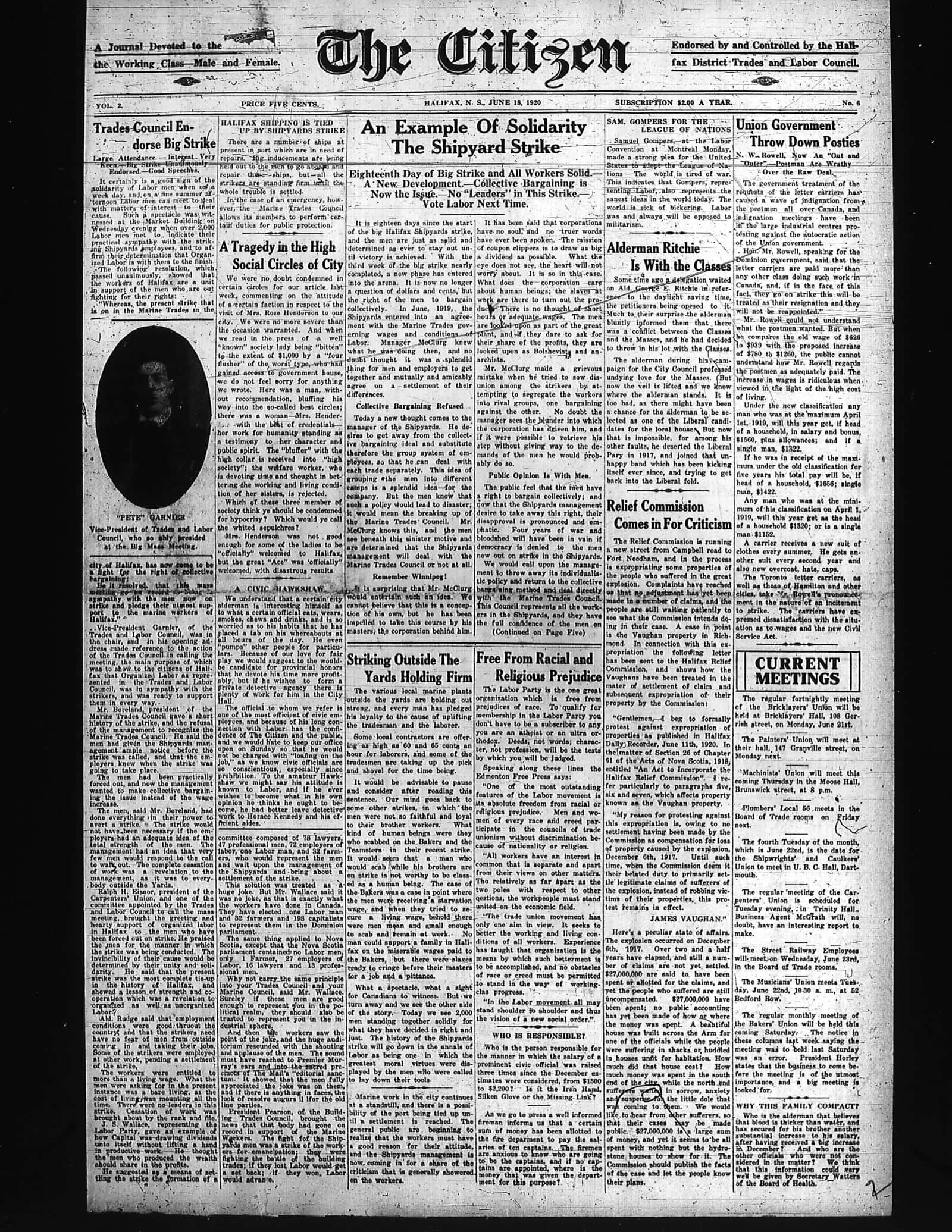

A still larger strike of shipyard workers broke out in June, 1920. Centring upon Halifax Shipyards Limited, it affected eight companies, an average of 2,000 workers, and lasted 52 working days. With the total loss of 104,000 man-days it accounted for over 12 per cent of the total strike days in Canada during 1920.

The strike would remain the largest single manufacturing strike to involve one community’s industrial workers until after World War II.

The International Typographical Union strike which lasted from May 1921 until August 1924 to establish the eight hour day was actually the biggest skilled-labour strike.

These strikes were an integral part of the powerful movement of workers and peoples near the end of and after the First World War, especially with the triumph of the October Socialist Revolution in Russia in November, 1917.

The main fear of the ruling elite after the Explosion especially as today, was the resistance and revolt of the workers and people against the imperialist war preparations and the danger of war and the capitalist system of exploitation on which it was based. On Armistice Day, 11 November 1918, Canadian Prime Minister Robert Borden wrote in his diary,

“Revolt has spread all over Germany. The question is whether it will stop there.”

The war was used by the Canadian state as a pretext to suppress organized labour and revolutionary politics – at home and abroad through military intervention to crush Soviet Russia. The War Measures Act remained in effect for over a year after the end of the war and was used against organizers of the Winnipeg General Strike of 1919.

The continuous struggle of the people of Halifax shows that imperialist war is not the inevitable future of humanity nor of the city itself. The striving for empowerment is the present reality that working people must embrace, nurture and use to secure their future.

See also: Tony Seed on the Halifax Explosion: No harbour for war!

Reproduced, with permission, from Tony Seed’s excellent blog.

With a special thanks to our generous donors who make publication of the Nova Scotia Advocate possible.

Subscribe to the Nova Scotia Advocate weekly digest and never miss an article again. It’s free!