KJIPUKTUK (Halifax) – December 6th is the centenary of the Halifax Explosion of 1917 – the largest explosion in history before the devastation of Hiroshima and Nagasaki by US atomic bombs. The tragedy is being marked by an intensive program of events and initiatives, including books, exhibits, radio and TV programs, memorial meetings and a stamp issued by Canada Post. The following article by Tony Seed reports on an initiative organized by anti-war activists in Halifax in 1983. It has been edited and expanded for this publication.

ON DECEMBER 14, 1983 a commemorative meeting was held on the occasion of the 65th anniversary of the Halifax Explosion by the Organizing Committee to Found the Halifax Committee Against Imperialist War. The meeting was the third in a series of forums held during the fall on the economics and politics of the imperialist war preparations.

Members of the committee researched and presented a paper “On the 65th Anniversary of the Imperialist Massacre of the People of Halifax.” They denounced the criminal propaganda of the magnates of Halifax, the press and some reactionary literary and cultural figures whose aim in their historical falsification of the events is to exonerate the war makers, the British imperialists and the Canadian bourgeoisie in order to create the psychology of war by implanting in the minds of the people the psychosis of the “military tradition” of Halifax. The Explosion-as-such is thus presented as an “act of God” and an exceptional “accident” caused by an inexplicable series of “oversights,” or manslaughter caused by the negligence of a ship’s captain or pilot, or even sabotage by “foreign agents” in league with “socialists” (from Quebec! from Russia!) as portrayed in the tawdry 1981 novel titled Sixth of December by Jim Lotz. Post 9/11, this disinformation became the leitmotif of the $10.4 million dramatic miniseries produced in 2003 by the state broadcaster the CBC titled Shattered City: The Halifax Explosion criminalizing the “enemy within” as the culprit and presenting American aid as “decisive” to the rescue and recovery efforts.

World War One was a carnage of unprecedented proportions, which took place from 1914 to 1918. As Lenin pointed out, it was fought between two coalitions of the imperialist bourgeoisie competing for the partition of the world, for the division of the booty, and for the strangulation of small and weak nations. He called it an enormous crime by an imperialist, violent, predatory, reactionary bourgeoisie. Despite this universal character of World War One, the Halifax Explosion is now being described 100 years later as having “brought home to North America the reality of the War in Europe” which was allegedly won by the “decisive” entrance of the United States, and reduced to chronicles of individual tragedy and heroism. The decontextualization of the tragedy and these spurious theories turning truth on its head aim to block Canadians from drawing the appropriate conclusions and acting against imperialist war preparations in the present.

The paper brought out “historical facts about the role of Halifax in the war plans of the imperialists in the First World War and how the Canadian bourgeoisie reaped enormous profits from the First World War and the use of Halifax in this regard.”

To the magnates of Halifax and the state, the organization of the city as a war port has been the self-serving “business” best adapted for the extraction of maximum profits since its founding by the British Empire in 1749. The location was always coveted by the English, who had attempted to penetrate and rule Nova Scotia from the colony of Massachusetts through the “old capital” of Annapolis; the conditions were very hostile, both for settlement as the most fertile land had been settled by the Acadiens, as well as the constant resistance of the Mi’kmaq Indigenous people and Acadiens, so those schemes were abandoned. Halifax was thus originally established as the new base by the Board of Trade and Plantations, an agency of the British state, for three main strategic and military purposes: (1) a place d’armes to smash the alliance between the Mi’kmaq Indigenous people and the Acadiens; (2) as a launch pad to attack the fortress of Louisbourg on Cape Breton Island of France, the traditional enemy of England, as part of the drive to conquer North America – an important naval-military fortification, Louisbourg guarded the approaches to the Gulf of St Lawrence and the northwestern Atlantic sea lanes; and (3) as a strategic base on the sea lanes between Europe, the Grand Banks fisheries which served the slave trade, the US and the Caribbean. Its location was a key to bringing the submission of the Caribbean with its rich colonies based on slave plantations owned by the English, Spanish, French and Dutch. Through the 19th century – during the Napoleonic Wars, the War of 1812, the first Crimean War of 1854-56, the U.S. Civil War and the 1898 Boer War – to the 20th century, Halifax functioned as the strategic base for the British naval fleet, the British Atlantic and West Indies naval squadron and, following the colonial Confederation of 1867, the deployment of Canadian ships and troops as cannon fodder for the wars of conquest of the British and American Empires through to the 21st century. On the Pacific Coast, Victoria, BC performed a similar, though less important role.

Nevertheless, although established in 1910 as an ostensible declaration of Canada’s independence from the imperial fleet, the RCN was the child of the Royal Navy. Its first ships were RN cast-offs. For the next forty years officers trained in the British fleet – their “big ship time” – and deployed and operated under British command, especially in the Caribbean, just as today Canada’s Maritime Command operates under the command of the US and NATO fleets – their “interoperability” – in the Black Sea, the Mediterranean Sea, Persian Gulf, Caribbean Sea and in the Pacific Ocean off the coast of Korea and Latin America.

By 1914 Halifax had become one of the most important North Atlantic ports – the port closest to Europe and ice free during the winter. Its role during World War I was the rapid movement of troops and supplies from Canada and the United States to Europe to participate in the imperialist war there. The pace of these shipments greatly intensified following the official entry of the United States into the war in April 1917. Between August, 1917 and November, 1918 a total of 50 convoys and about 500 ships cleared the port. Far from bringing “benefits,” this brought disaster to the people. While the bourgeoisie was amassing enormous profits out of war orders – the transshipment of military materiel and troops, from servicing, refuelling and victualling of the Royal Navy and thousands of cargo ships, and the revival of the sugar trade with the West Indies – tremendous exploitation of the workers ensued, while in the port even the most elementary rules of navigation and precaution were thrown to the wind due to the pressure to accelerate the movement of the maximum number of ships in minimum time.

The paper showed how it was the British Admiralty which was responsible for the day-to-day administration of the port and the organization of convoys, and which was directly responsible for the series of events leading to the explosion of the MontBlanc, a French rust bucket overloaded with 3,200 tons of high explosives [1], purchased in New York, in the wake of its collision with the Imo, a Norwegian relief ship in the Halifax Narrows. The former was enroute to the inner harbour of the Bedford Basin, five miles long and three miles wide, used as a staging ground for trans-Atlantic convoys, having been cleared by the British authorities to enter the harbour despite two telegrams sent December 2nd from New York as to the danger of the cargo. The IMO was outbound. The federal cabinet of Canadian Prime Minister Sir Robert Borden, the U.S. authorities who consciously diverted the badly-loaded Mont Blanc with its lucrative cargo from the port of New York to Halifax, and the British authorities were all aware of the threat. It was a war crime:

- Borden knew explicitly how ad hoc the existing arrangements were for public safety, where everything was left to chance;

- This danger was increasing with the freezing of the St. Lawrence River as slow convoys also departed from Halifax – which otherwise embarked from ports on the St. Lawrence – putting an even greater strain on the already overburdened port facilities;

- Borden implicitly understood the potential for civil mayhem that any mishandling of ordnance might unleash;

- Borden ordered no special advance budgetary or other provision;

- Ottawa had told Canadian naval officials in Halifax to interfere as little as possible in local conditions;

- Borden brought no pressure on the British Admiralty – the marshalling of convoys from Halifax, the main base of the British naval fleet, was under the direct command of the North America and West Indies Station of the Royal Navy – before the Explosion to exercise special care;

- The Halifax Pilotage Authority was a nest for political patronage; and

- Borden treacherously dismissed calls to bring damage claims after the war against Britain or France (responsible for the Mont Blanc) who were culpable under maritime law. [2]

As a result, according to the understated official figures, 1,963 innocent residents of the city were killed, another 9,ooo injured and 199 blinded – almost one fifth of a total population of less than 50,000 – 5,000 of whom were soldiers and sailors. One square mile of the working class quarter of the North End was totally destroyed. 6,000 lost their homes altogether and over 20,000 Haligonians were left homeless and destitute, including ten thousand children. More than 1,600 buildings were destroyed, and 12,000 more were damaged. Many died as buildings collapsed and burned around them. The explosion flattened every building at the shipyard of the Halifax Dry Dock Company, where seven ships were being repaired, killing some 120 workers. Likewise, the management of the huge Acadian Sugar Refinery refused to evacuate the waterfront factory; scores of workers were killed standing on the roof watching the drifting ships in the moments before the fatal explosion.

The force of this explosion was so great that people in Truro, over 100 kilometres away, felt the tremor. A mushroom-shaped cloud rose several kilometres high, and 3,000 tons of the splattered ship rained down on the area. The ship’s gun landed two kilometres away near Albro Lake on the northern Dartmouth side of the harbour. The huge black anchor from one of the ships, the Mont Blanc, blew over the peninsula south to land on the far side of the North West Arm five kilometres away, where fragments remain to this day in the Dingle Park. The Narrows was boiling with the splashes of shrapnel. Also falling were rocks, believed to have been sucked up from the harbour bed.

The intense heat of 5,000 degrees Celsius at the explosion’s core was so intense that water surrounding the Mont Blanc immediately vapourized – exposing the sea bed 60 feet below – resulting in an on-rush of water to fill the void. This triggered enormous water activity. Hundreds of workers drowned when the resulting steaming tidal wave, a mini tsunami, reached shore. The wave, boiling with hot metal fragments, flooded low-lying streets more than six metres (20 ft.) above the sea. It is estimated that as many as 3,200 people or more were killed, taking into account the hundreds of people and children including Mi’kmaq children working and living along the shores of Halifax and Dartmouth who disappeared in the tidal wave. The explosion severely damaged the segregated African Nova Scotian community of Africville and wiped out Turtle Grove, the Mi’kmaq reservation in the Tufts Cove area on the Dartmouth side of the harbour. Members of both communities were denied relief and compensation by the official Halifax Relief Commission. [3] By nightfall another factor was to contribute to the final death toll – the worst winter blizzard for years.

Through a series of trials confined to technicalities – an inquiry which started in December, a criminal manslaughter trial which started in February 1917 and a civil court case which dragged on into the 1920s – blame was attributed to two pilots, the French captain and a junior British naval officer, but in the end no official blame was ever affixed nor a cent of compensation demanded from the war criminals by the Borden government.

The appalling mass slaughter of millions as the Great Powers with the active participation of the Canadian ruling elite sought to redivide the world with crass disregard for the human cost was not confined to Europe nor to Halifax. It merits attention that already – just four months before the Halifax Explosion – a massive explosion had rocked a coal mine in New Waterford, Cape Breton, on July 25, 1917. It took the lives of 65 men and boys alike, some as young as 14 years old – with dozens of other injuries from rock and gas. The Anglo-American Dominion Coal Company was pushing to increase production for the war, and workers described laxity in safety standards, ventilation, and proper maintenance. Dominion Coal immediately placed the blame on “human error” and cowardly singled out a deceased miner, John MacKay, as the culprit. Due to the pressure of the coal miners, criminal charges successfully brought by a New Waterford Grand Jury against two mine officials and a government employee were callously dismissed by the Nova Scotia court as part of a class system which made and still makes such barely imaginable losses and tragedies possible. [4] Official histories do not mention the “coincidence.”

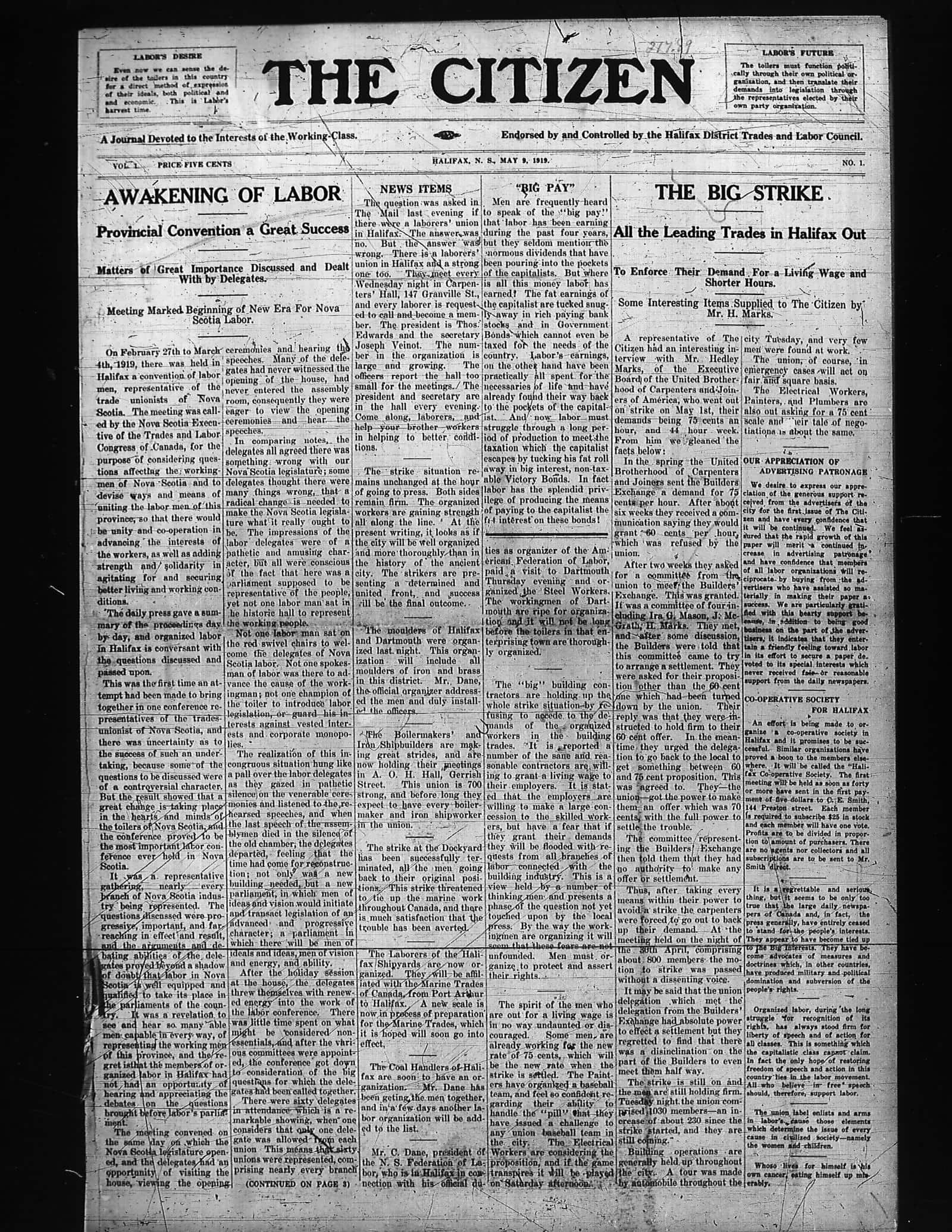

The paper also brought out “new historical facts about the struggle waged by the workers and the people against the imperialist war, their exploitation and calamitous situation after the war. The Halifax workers rose against the injustices and profiteering from the misery prevailing after the Explosion, culminating in a general strike of over 1,000 building trades workers launched on May Day, 1919 – the largest strike in the history of Halifax.”

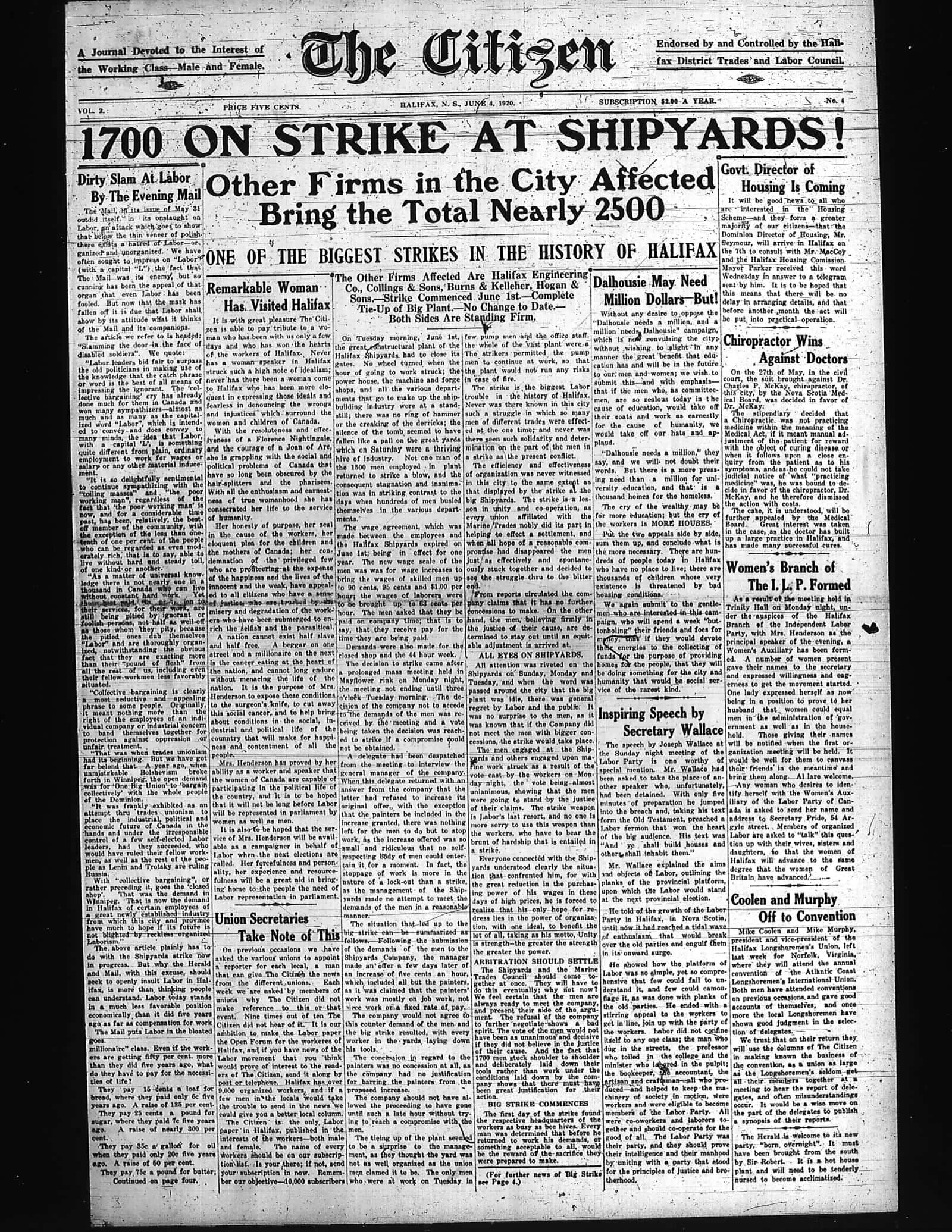

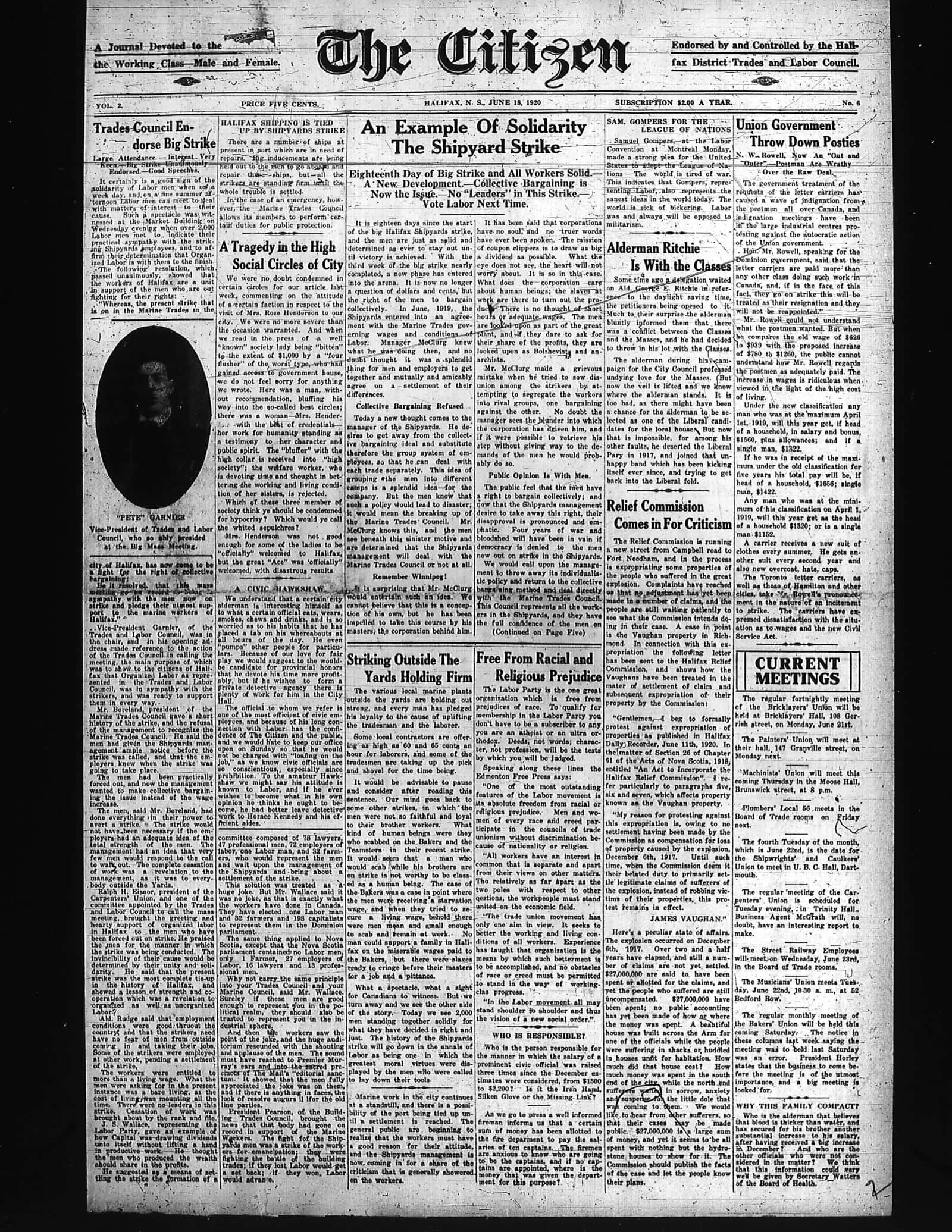

A still larger strike of shipyard workers broke out in June, 1920. Centring upon Halifax Shipyards Limited, it affected eight companies, an average of 2,000 workers, and lasted 52 working days. With the total loss of 104,000 man-days it accounted for over 12 per cent of the total strike days in Canada during 1920. [5]

These strikes were also an integral part of the powerful movement of workers and peoples after the First World War, especially with the triumph of the October Socialist Revolution in Russia in November, 1917. The continuous struggle of the people shows that imperialist war is not the inevitable future of mankind and of the city. The paper showed that the main fear of the bourgeoisie after the Explosion especially as today, is the resistance and revolt of the workers and people against the imperialist war preparations and the danger of war. The war was used by the Canadian state as a pretext to suppress organized labour and revolutionary politics. The War Measures Act remained in effect for over a year after the end of the war and was used against organizers of the Winnipeg General Strike of 1919.

In conclusion, the 1983 paper pointed out as its central thesis that the tragedy of the Halifax Explosion, the subsequent Naval Magazine explosion of July 1945 and other preventable incidents since then shows that the granting of military-naval concessions and other privileges to the superpowers and their naval fleets represent nothing but great danger to the democratic right of the people to live in peace and to their freedom.

The people of Halifax have suffered enough in the past and do not want the warships in their city or in Canada.

In these conditions, it is a historic necessity for the people to enhance their vigilance and increase their opposition to the imperialist war preparations. including the “visits” of the warships and marines of the imperialists, both conventional and nuclear.

Only uncompromising struggle is the guarantee against a repeat of these disasters and will ensure that the people will be able to live in peace.

“Commemorative Meeting Held on the Occasion of the 65th Anniversary of the Halifax Explosion,” Halifax People’s Voice, published by the Organizing Committee to Found the Halifax Committee Against Imperialist War (HCAIW), December, 1983. This organization evolved into the No Harbour for War group, which is active in Halifax today. Edited and expanded for this publication by the author, with a file from Gary Zatzman.

Notes

1 The Mont Blanc was literally a merchant ship of the notorious “merchants of death” of WWI, the war profiteers. The lucrative value of the Mont Blanc’s cargo of explosives:

Explosives Quantity Value in 1917 US$

of the TNT 226,797 kg $240,750

Wet picric acid 1,602,519 kg $2,230,999

Dry picric acid 544,311 kg $960,000

Guncotton 56,301 kg $65,165

Benzol 223,188 kg $104,376

Totals 2,653,115 kg $3,601,290

Data from the 1992 Ground Zero conference, organized by Alan Ruffman, an independent marine geophysicist, and historian Colin Howell of the Gorsebrook Institute, which, for the first time, publicly involved science in analyzing the explosion. The historiography of the Explosion-as-such was so mythological that even the precise time of the explosion had been left in the shade. The independent researchers obtained local seismographic charts (which had been all acquired by Colombia University and are now stored there) to put to rest the mythological rendition of precisely what time the explosion had occurred (9:04:35 am). And they also discovered a darker, more disturbing relationship. Scientific analysis of the Halifax Explosion was carried out by Oppenheimer’s group in the Manhattan Project in 1942 in building weapons of mass destruction that served America’s own imperialist ends, the atomic bomb, to be targeted at highly populated, urban centres.

Writing of this universal dimension, Dr Ruffman notes: “…it is clear that the Halifax experience (helped scientists to) gauge the range of air blast effects and to estimate any possible tsunami created by a blast in a populated harbour city.” He says the Halifax Explosion helped the American scientists in their decision to detonate bombs in mid-air at urban Hiroshima and Nagasaki in Japan, to produce a greater range of devastation: “Their research into what had gone before – including the Halifax Explosion – gave them insight into the potential of a nuclear bomb.” [3] One crime was the handmaiden of the other.

Ground Zero: A Reassessment of the 1917 Explosion in Halifax Harbour,Nimbus & Gorsebrook Institute; 1993

2 In 2002 a scholarly book The Halifax Explosion and the Royal Canadian Navy partly exonerated the Canadian navy, which had been vilified by some media. Author John Griffith Armstrong reveals certain memos – a kind of “reality check” – that had been prepared for the government by the Dominion wrecks commissioner, Capt. Louis Demers. They implicate the entire Borden cabinet in deciding, collectively, to ignore naval service complaints about the chaotic standards of harbour pilotage at Halifax. See “Time to disturb the sleep of the unjust,” a review by Gary Zatzman of John Griffith Armstrong, The Halifax Explosion and the Royal Canadian Navy: Inquiry and Intrigue (Vancouver: UBC Press, 2002). <http://www.shunpiking.org/ol01…/05HfxExplosionBookReview.htm>

3 The history of Turtle Grove, a small community that dated back at least to the late 1700s, remains largely unknown; it was already under an expropriation order issued in 1917, was never rebuilt and its survivors were resettled on other reserves. Reclaiming History, a 2000 exhibit of the Art Gallery of Nova Scotia curated by Jim Logan, an artist who was the AGNS’s First Nations curatorial resident, included Alan Syliboy’s painting titled “Tufts Cove Survivor”, which laments and honours the Mi’kmaq settlement of Turtle Grove.

4 Suzanne Morton, “Labourism and Economic Action: The Halifax Shipyards Strike of 1920,” Labour/Le Travail, Volume 22 / Volume 22e (1988)

5 Lachlan MacKinnon, “New Waterford’s Fatal Day: Memorializing the New Waterford Colliery Explosion, 1917-2017,” The Acadiensis Blog, October 4, 2017,

Reproduced, with permission, from Tony Seed’s excellent blog.

If you can, please support the Nova Scotia Advocate so that it can continue to cover issues such as poverty, racism, exclusion, workers’ rights and the environment in Nova Scotia. A pay wall is not an option since it would exclude many readers who don’t have any disposable income at all. We rely entirely on one-time donations and a tiny but mighty group of kindhearted monthly sustainers.