KJIPUKTUK (Halifax) – Food banks are a wonderful institution, its volunteers deserve our deep gratitude, and in these times of austerity-induced suffering they need our full support.

That said, food banks are not very efficient in getting food to hungry families.

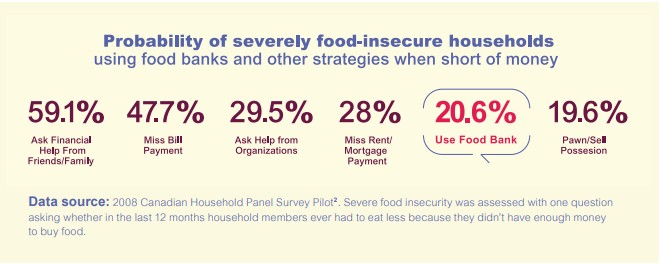

A recent study found that in 2012, there were 5 times more people living in a food-insecure household than those accessing a food bank. In fact, food bank use was one of the least common strategies employed by severely food-insecure households when they were short of money.

“We found that most food-insecure households delayed bill payments and sought financial help from friends and family, but only 21.1% used food banks,” the authors of a study conducted among others by food security expert Valerie Tarasuk state.

Tarasuk is a professor in the Department of Nutritional Sciences at the University of Toronto, and a driving force behind PROOF, an interdisciplinary research team that looks at household food insecurity in Canada.

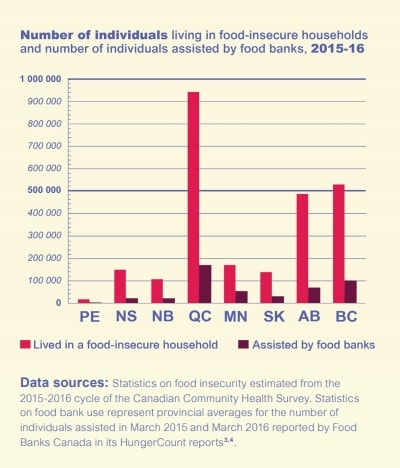

The above table, taken from a fact sheet issued by PROOF, shows how the disconnect manifests in several Canadian provinces, Nova Scotia among them.

Statistics Canada counted some 150,000 Nova Scotians as facing food insecurity at any time in 2016, yet Hunger Count, an annual report by Food Banks Canada, shows that Nova Scotia food banks only supported an average of 24,000 individuals in March of 2016 and the same month in the previous year.

In May 2018 I interviewed professor Valerie Tarasuk about food banks and related issues of food insecurity.

“Researchers have known this for a long time. But for ordinary people it’s startling. For so long in Canada we have had these annual HungerCounts. Even the name hunger count suggests it counts the number of people in Canada who are hungry. But it doesn’t. It counts the number of people who use a particular kind of service. The HungerCount reports recognize this, but the slippage occurs when the media gets hold of them,” Tarasuk told me.

“The discrepancy between food bank use and food insecurity tells us that the problem is way bigger than we thought it was. As we delve more deeply into the demographics of the people who are food insecure, or consider the health implications, the other thing we can say is that the problem is also way more serious,” she said.

While food banks don’t solve food insecurity, money does, Tarasuk said, pointing to the effectiveness of policy changes that support poor people, such as the dramatic reduction in poverty once people qualify for old age pension and guaranteed income supplements.

“What is discouraging to me is the number of government initiatives that continue to fuel food banks as a response. Many provinces have introduced tax credits for farmers who give to food banks, back in the nineties we had these good Samaritan laws that absolved corporate donors from liabilities in terms of the health and safety of the food donated,” Tarasul told me at the time.

“It’s concerning how we continue to busy ourselves with these little things and further entrench these responses, as if it is somehow going to do something about food insecurity. It’s not accountable. It’s very cheap for government to make these gestures, as opposed to revamping the welfare system, to make it so that people are no longer food insecure,” she said.

With a special thanks to our generous donors who make publication of the Nova Scotia Advocate possible.

Subscribe to the Nova Scotia Advocate weekly digest and never miss an article again. It’s free!