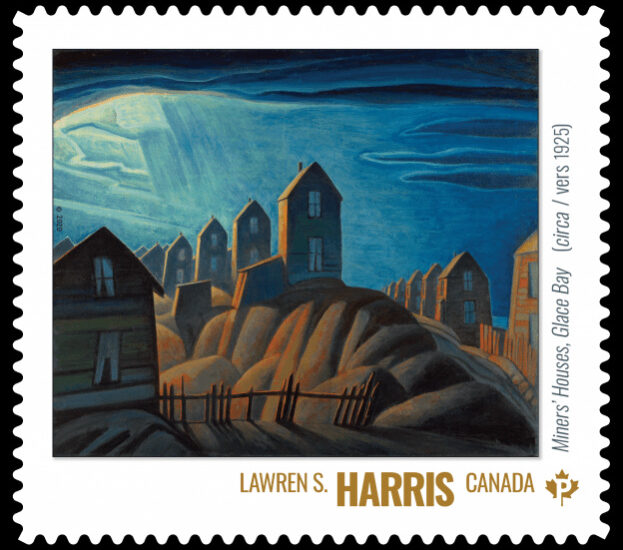

I think I first learned about this remarkable painting when my friend Allen Seager sent me a postcard from the Art Gallery of Ontario. Eventually I used it as the cover illustration for my biography of the union leader J.B. McLachlan. More recently, it was featured in an exhibition at the AGO and in a documentary film. It is in the public eye again with the release this spring of stamps to mark the centennial of the first public show by the Group of Seven. Among the seven stamps, Lawren Harris is represented by Miners’ Houses, Glace Bay (1926).

This was not the most obvious choice. Only a few years ago, one of Harris’s iconic images of the north, Mountain Forms (1926), broke the record for Canadian art prices when it sold at auction for $11.2 million. But the lesser known Miners’ Houses was a very good choice. Within its limits, this is a “labour stamp” that acknowledges the often-overlooked working-class presence in Canadian history. It also opens up interesting questions about Harris’s social and political engagement and his evolution as an artist.

Miners’ Houses has been read variously, as an expression of the artist’s personal struggle with depression over his brother’s death in the Great War and as an example of his longstanding interest in depicting working-class housing. It has also been described as an important and eloquent statement on social justice. The most explicit origins for this painting, however, are found in Harris’s visit to Glace Bay in April 1925, at a time when the Nova Scotia coal country was convulsed by a long and bitter strike.

For months, the coal miners had been working short-time in what amounted to a long-running lockout to prepare them for wage cuts or worse. After the contract expired in January, the British Empire Steel Corporation abandoned attempts to reach an agreement. Instead, they hoped to rid themselves of the union entirely. Throughout North America, coal operators were driving the United Mine Workers of America out of the coalfields. To a large extent they succeeded, as membership fell from 400,000 to 100,000 in the course of the decade. But not in Nova Scotia, where the union survived thanks to the tenacity of the local resistance.[i]

From the beginning of the year, much public attention focused on conditions in the Nova Scotia coalfields. J.S. Woodsworth visited in January and launched an emergency debate in the House of Commons. Agnes Macphail also came, and went back to Ontario to speak about the miners’ destitution and determination. In early March, the suspension of credit at the company stores, which many families depended on, set off the anticipated strike. In the following weeks, several daily newspapers opened appeals for funds to support the miners and their families. Among them was the Toronto Star, which sent nightly cheques to the relief committee in Glace Bay. This was the immediate context that led Lawren Harris to take the train to Glace Bay, with plans to raise funds and write for the Star.[ii]

One of Harris’s first stops was with the Rev. Dr. Francis McAvoy, a Baptist minister who had started relief efforts several days before the strike began. McAvoy organized a Central Relief Committee that mobilized support from local merchants. They took over the YMCA building, and opened relief stations in several parts of town. “Only by the quickest thinking and most strenuous work could McAvoy and his committee keep one day ahead of starvation,” wrote Harris. With initial funds from the town council and the miners’ union in hand, McAvoy also took the lead in launching appeals for outside support. He continued to lead the campaign throughout the five months of the strike.

Harris found McAvoy, a man of his own age, to be a thoroughly heroic figure and drew a respectful sketch of him to accompany his report. The Glasgow-born McAvoy had come to Ontario as a young man in 1904. After losing his left arm in a farm accident, he was employed at the Massey-Harris foundry in Brantford for several years. Harris himself was born in Brantford (but moved to Toronto as a child) and grew up in wealth and privilege as the grandson of one of the founders of the company that became Massey-Harris. It is possible Harris and McAvoy were known to each other, perhaps through the Harris family ties in the Baptist Church, but there seems to be no direct evidence for this.

After leaving the foundry, McAvoy served as a Salvation Army officer in St. Stephen, New Brunswick and then attended Acadia University for degrees in arts (1919) and theology (1920). He also pursued further studies in the United States.[iii] By the time he arrived in Glace Bay as a minister with his wife and daughter in 1922, McAvoy was preaching a social gospel that met with Harris’s approval: “From his first day, he interested himself chiefly in the miners. He preached economics, he employed charts, he talked politics, but he brought everything to its human equation.” And, wrote Harris appreciatively, “He teaches them that there is no such thing as independence, that men are interdependent and that is the basis of brotherhood.”

While admiring McAvoy’s efforts, Harris was appalled by the surrounding landscape, which he described in visceral terms: “Glace Bay is really no town, but a number of huddles of box-like houses around scattered coal mine mouths. . . . It’s drab and dreary and bedraggled even on a sunny day. The miners’ houses are in monotonous rows on either side of beaten earthen lanes . . . ” Here we already see the outlines of Miners’ Houses, whose distorted buildings have been read by curators as evidence of “the psychological condition” that weighed on towns like Glace Bay.[iv] As Harris wrote, “Here we see the hard, bare facts underlying the industrial machine — and it’s not a pretty sight. Glace Bay is like a giant bound by a million cords, bound so that he cannot move and straining every muscle to the limit to find a loose cord, or a cord that will give or snap and so ease the pain, or perhaps, but this is a far off dream, give him freedom.”

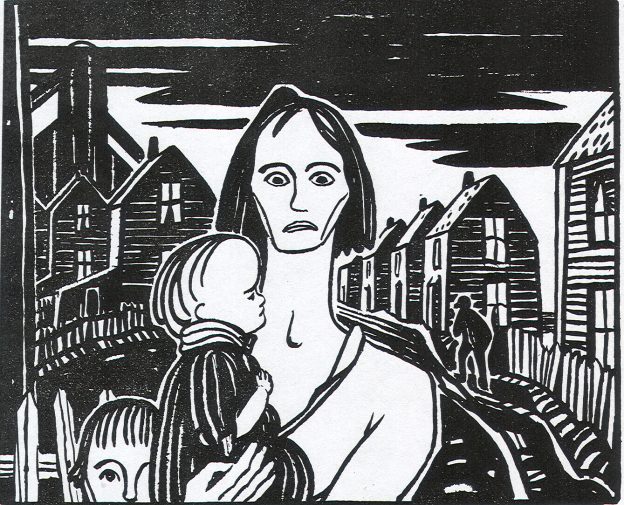

Harris generally identified with the progressive nationalism and social-democratic politics of Canadian Forum, which published regular editorials on the coal strike that year and appealed for support for the coal miners. On his return to Toronto, Harris gave the magazine a sketch of a woman and her children set against a backdrop of company housing, fences and pitheads. A lone man trudges home along the road behind them. This was published in the July 1925 issue, with the title Glace Bay, and may be considered a preparatory sketch for Miners’ Houses.[v]

That stark image, with its expressionist echoes of Edvard Munch, made a strong impression on Emily Carr when she visited Harris’s studio in 1927: “He showed me a black and white sketch inspired by the coal strike in Halifax. A woman, distraught, gaunt, agonized, carrying a child who was pitiful, drooping, hopeless and dumbly submissive. Half of the face of another child was cut by the bottom of the picture. The background was houses, black and desolate. There was a thunderous, stupendous horror in the air. The woman’s eyes were wild and frantic. Some day he will make a canvas of it. It will be terrific.”[vi]

It is often noted that the Group of Seven were more interested in landscapes than people, and that Harris himself frequently turned his attention to the exteriors of homes inhabited by the urban working class. In 1921, the critic Barker Fairley, a strong ally of the Group’s efforts to create a new Canadian art, made a perceptive comment about Harris’s urban scenes: “Perhaps as time goes on he will shift the emphasis somewhat from the buildings people inhabit to the people themselves.”[vii]

But Harris did not paint the canvas Carr imagined, or that Fairley might have preferred. The women and children of Glace Bay were in effect erased from the final picture. In fact, Harris had already finished Miners’ Houses more than a year before Carr’s visit. In May 1926, a review in the Toronto Star described the painting as “a powerful satire on industrial peonage” that “looks like a scene from Dante’s Inferno” — “thin, starved houses stand like sepulchral monuments” and the street “like a stream of lava.” The only hopeful sign was “a shaft of vengeful light” cutting through the sky “as if signifying the impending wrath of Heaven.” As the Harris biographer James King notes, “The world of the miners is one of black oppression, but the picture seems to offer a glimmer of supernatural assistance.”[viii]

Miners’ Houses is indeed notable for the absence of people. We are driven to ask, how did the men, women and children of the coal country respond to the cruel environment Harris depicted? Were they only victims? Did these people have any power to address their poverty and exploitation?

As a wealthy outsider, Harris did not fully recognize the depth of family, community, and class identities in places such as Glace Bay. Out of all the terrible suffering of the 1925 strike, which culminated in the shooting of William Davis by company police at Waterford Lake, there were also elements of triumph. The strike ensured the survival of the union and contributed to the downfall of the British Empire Steel Corporation. In the long run, the coal miners made their mark on history by helping to create a legacy of resistance to the destructive and dehumanizing forces of industrial capitalism.[ix]

From his writings, both published and unpublished, we know that Harris was not indifferent to demands for attention to the condition of the working class. In 1925, he represented this theme in the mother and children of Glace Bay and in the working-class parson Francis McAvoy. Moreover, it is notable that in 1925 Harris completed a large and luminous portrait of Salem Bland, a tribute to the apostle of the “new Christianity” of the social gospel. That painting has been described as a “corollary” to Harris’s anguished response to the 1925 strike.[x]

But it is also true that Harris by this time was turning away from the fractured realities of urban life and industrialism and seeking regeneration in the imagined purity of the north, a theme that often defines his popular image as an artist.[xi] This turn, strongly influenced by Harris’s theosophy, was well underway before 1925.

When we compare Miners’ Houses and Mountain Forms, we see that they have more in common than the fact that they were completed in the same year. Both paintings are alive with unseen mysteries of menace and promise, and the mounds of earth and steep rooftops in Miners’ Houses bear a striking resemblance to the rock formations and glacial peaks of Mountain Forms. As a statement on social justice, Miners’ Houses confirms Harris’s personal vision of a social environment in need of cosmic redemption. The miners’ dream of freedom remains far off, but in his own search for spiritual transcendence, Glace Bay made a lasting impression on Harris.

David Frank is a professor emeritus in Canadian history at the University of New Brunswick. He is the author of J.B. McLachlan: A Biography (Toronto: James Lorimer and Company, 1999).

This article was originally published on ActiveHistory.ca, a website that connects the work of historians with the wider public and the importance of the past to current events. Republished with the author’s kind permission.

See also: The Economic Gospel of J.B. McLachlan, 1919

Notes

[i] For a summary, see Poster #15 from the Graphic History Collective: “Standing the Gaff : Cape Breton Coal Strikes, 1920s,” https://graphichistorycollective.com

[ii] Toronto Star, 25 April 1925. Quotations from Harris are from this source.

[iii] For McAvoy, see Carole MacDonald, Historic Glace Bay (Halifax: Nimbus Publishing, 2009), pp. 58-60. See also Records of the Graduates of Acadia University, 1843-1926 (Wolfville: Acadian Print, 1926), p. 224.

[iv] Text accompanying Miners’ Houses in “The Idea of North: The Paintings of Lawren Harris,” Art Gallery of Ontario, 2016.

[v] The drawing is reproduced on the cover of Dawn Fraser, Echoes from Labor’s Wars: The Expanded Edition (Wreck Cove, N.S.: Breton Books, 1992).

[vi] Hundreds and Thousands: The Journals of Emily Carr (Vancouver: Douglas & McIntyre, 2006 [1966]), p. 39.

[vii] Quoted by James King, Inward Journey: The Life of Lawren Harris (Toronto: Thomas Allen Publishers, 2012), p. 128.

[viii] King, Inward Journey, p. 175.

[ix] See “The Legacy of Coal: The Staple Trap,” posted 6 December 2016 on the Acadiensis Blog.

[x] King, Inward Journey, pp. 176-77.

[xi] For a review of the 2016 show, raising questions about Harris’s conflicted social position and his erasure of indigenous and working-class themes, see David Merray Caoimhe, “Whose Idea of North? Lawren Harris at the AGO,” canadianart, 7 July 2016.