KJIPUKTUK (Halifax) – How many times have we been reminded that we should be working towards a “just recovery” from this pandemic? Let’s get rid of the inequities that plague us as a society – take advantage of the crisis to fix homelessness, provide a decent living for all, improve the situation of our elderly. Inequities in the way children have survived the closing of schools will become more obvious as the school year progresses, and need to be fixed – why not for good?

Parents, teachers and children experienced more than the usual first day of school jitters this year. For some teachers, the jitters approached panic as they contemplated the unpacked boxes, the new routines to be learned, the furniture to be disposed of, the faulty ventilation needing to be fixed – all the extra tasks that teaching in a pandemic creates. On top of that many have fears about the safety of the students and staff as a result of government plans that seem hastily put together and contradictory to scientific evidence.

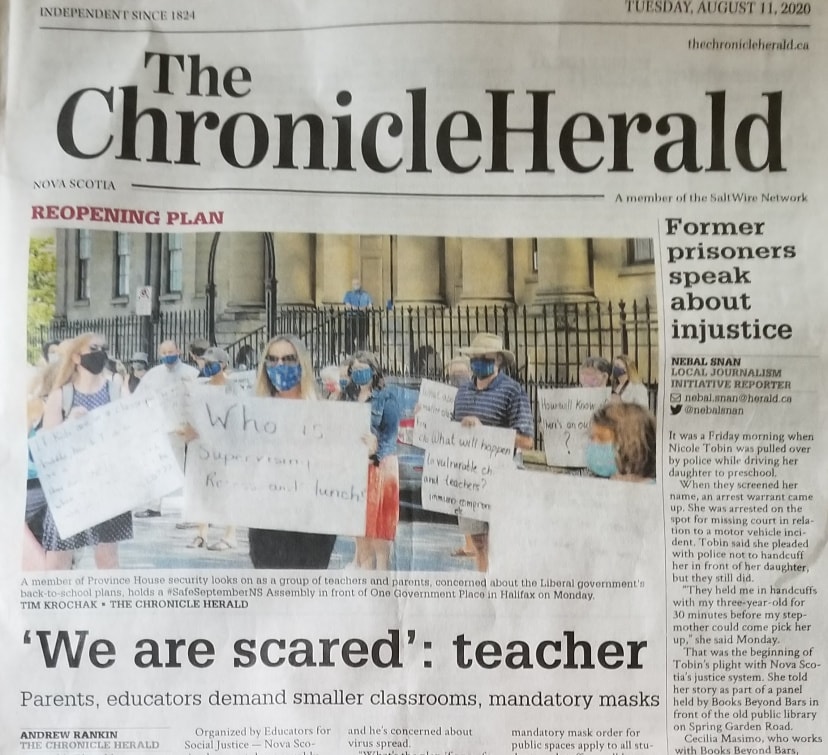

In Nova Scotia, that sense of doom is compounded by a premier whose “angry dad” persona telling them it’s time for teachers to “step up” (as if they haven’t been preparing, planning and shopping for weeks) and who has denigrated their union, ignored a petition signed by 11,000 parents and supporters and dismissed their concerns. The abolition of school boards two years ago, and the removal of principals from the Nova Scotia Teachers Union (NSTU) has deepened the sense that there is nowhere to turn, no one to answer very legitimate questions and no recourse if things go wrong.

What is behind all this angst? After all, we do have very low rates of COVID at present, and almost zero community transmission, so surely it’s okay to restart school with some basic health protocols? And everyone recognizes the need for children to be back in school – both for their development and health and to allow parents to get back to work.

I see two major reasons behind the fear of many parents and teachers. The first is that we have been told repeatedly that a second wave is coming, and that it may well be worse than the first if precautions are not taken. We’ve had the idea of two metre physical distancing drilled into us, and our government has used this as an excuse to shut down the legislature and all its committees for the past six months. Why then is it suddenly okay to have schools open up in seeming disregard for this basic precaution, especially in view of the “inevitable” second wave?

The second reason is the fear that some of the changes being implemented will set back education instead of being part of a “just recovery”. For years, waves of austerity and neoliberal policies have underfunded education, undermined staff unions and pushed a privatization agenda that has threatened what is one of the best public education systems in the world. Smaller classes, enriched arts and science education and progressive teaching methodologies have been proven to promote excellence in education as well as equity – socio-economic background has less effect on academic achievement here than in many countries. Many provinces have disregarded this research.

Given these factors, teachers and parents all across the country have been calling for smaller classes, backed up by the report from the Sick Kids hospital in Toronto. “Smaller class sizes should be a priority strategy as it will aid in physical distancing and reduce potential spread from any index case” p. 10. The ideal for Canada would be 15-20 children in a room – this would allow for better physical distancing, but more importantly creating these small cohorts or bubbles would make contact tracing and quarantining those contacts much more manageable in the event of an outbreak. Denmark opened schools last spring with success – with bubbles of no more than 12 children. It would also allow the youngest children to play and learn freely without masks. There have been many creative suggestions about how this could be achieved with minimal expenditure (many hoped that the new federal money would have been spent on this) – hiring extra staff, utilizing community spaces and extra rooms in schools, and putting older, more independent students on shifts so that their classrooms could be used for younger cohorts.

With few exceptions across the country none of these suggestions have been implemented; the one province that seems to have listened to this advice is New Brunswick, where P-Gr. 2 classes are capped at 15, Gr. 3-5 classes are “reduced where possible” and high school students go on shifts, but have classes reduced to respect physical distancing.

Many teachers and parents are asking – how come New Brunswick can do this, and we can’t? It is certainly no richer that we are, but perhaps they are taking the longer view – implementing changes that may result in positive benefits to education after this is all over. Or perhaps it is just based on the best available research at this point in time.

Whatever the reason, New Brunswick is pretty much alone across the country. No other province is actively reducing class sizes – two provinces however are overtly encouraging parents to keep their children at home with government directed online learning plans…originally it looked as if that was the way they would reduce in-person class sizes. However, it now appears that Ontario is forcing parents to pre-register their children for in-person classes, and then collapsing classes so that many elementary and middle school classes are even bigger. Alberta is also encouraging online learning, and at the same time loosening up the restrictions for charter schools, under the guise of promoting school choice (for a look at the failure and drastic consequences of this movement, check out https://networkforpubliceducation.org). Both these provinces have premiers who are definitely from the non-progressive Conservative (or Reform) end of the political spectrum, and the fear is real that the pandemic is playing into their plans to further undermine public education. At this point, between 30% and 40% of children in those provinces are being kept home this year.

Quebec, at the opposite extreme, is making in-person attendance at school mandatory. If the rationale for this seems mystifying, one just has to look at France, which also has instituted mandatory attendance. When France passed no hijab/face covering rules, Quebec followed – one wonders how that is going now. And again, it will be interesting to see how mandatory attendance is enforced, particularly given that both places have relatively high levels of COVID right now.

Both Quebec and Alberta, who started school earlier than other provinces, already have cases of COVID in schools – in Alberta, cases in 11 schools have resulted in hundreds of students having to quarantine for 2 weeks.

A look at the various provinces’ masking policies is also instructive. All provinces have rules in place that require at least the older children to wear masks on buses and in common areas of the school. Only Ontario and Nova Scotia have instituted a policy which says that all students from grades 4 – 12 must wear masks in the classroom as well. Here, it seemed like as soon as the government realized that masking in class was an option, great, they could abandon all pretence of physical distancing. They are not taking into account how this will affect learning, how it will be enforced, and what happens when students defy the rules. In middle and high schools where large classes of over 30 are common, this is a real concern, particularly given the new research that says that children over the age of 10 are just as likely to get and transmit the virus as adults.

School has started, but it’s not too late for governments to listen to the experts (teachers, medical professionals, parents) and make plans to transition to smaller classes now before a second wave hits us and forces us to shut down schools entirely. In Nova Scotia we are already suffering from the teacher shortage we have been predicting for years now, and this has been given as one barrier to smaller classes.

A show of trust in teachers, along with the chance to teach the way they know is best in smaller groups might go a long way to tempting some disaffected teachers back into the profession. The money it would cost is the best investment in our future – maintaining a strong, progressive public education system that would address the inequities that have been exacerbated by this pandemic. After all, who wants to return to normal? We can do better!

This article was originally posted on Molly Hurd’s blog: The Inquiring Teacher. It’s re-posted here with Molly’s kind permission.

Molly Hurd’s perspectives on education have been developed out of her wide variety of teaching experiences in northern Quebec, rural Nova Scotia, Nigeria, Tanzania and Britain. She was also a teacher and head teacher at Halifax Independent School for twenty years. She believes passionately that keeping children’s natural love of learning alive throughout their school years is one of the very best things a school can do for its students. She is the author of “Best School in the World: How students, teachers and parents have created a model that can transform Canada’s public schools” published by Formac Publishing in 2017.

With a special thanks to our generous donors who make publication of the Nova Scotia Advocate possible.

Subscribe to the Nova Scotia Advocate weekly digest and never miss an article again. It’s free!