KJIPUKTUK (Halifax) – David Patriquin will be the first to tell you that he isn’t a forestry expert, just a retired biologist who is concerned about the state of Nova Scotia’s forests.

That may be, but when he speaks people tend to listen. In a recent post on his website Patriquin describes what he views as a disturbing trend to aggressively target relatively plentiful old forest stands in Southwest Nova Scotia.

The title of his piece more or less tells the story: Landscape-level “Log the best and leave the rest” on Nova Scotia’s Crown land forests.

It’s an important article, but it presupposes quite a bit of knowledge, and we decided to give David a call and ask him some questions.

In the article Patriquin remarks on how the forestry industry, via the Westfor consortium, is focused on woodland in Southwest Nova Scotia these days.

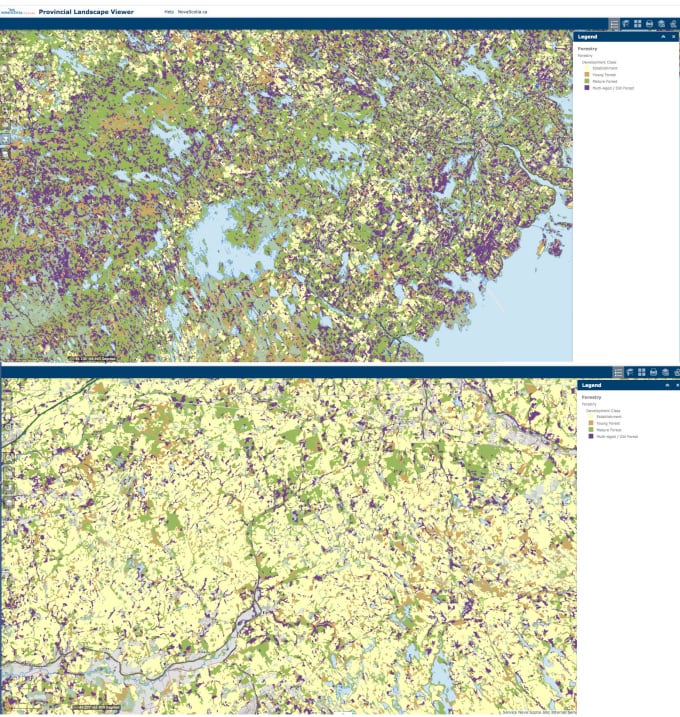

Why are they going there? Well, if you look at a map you see that’s where all the remaining concentrations of high volume, old forest in this province are located, he tells the Nova Scotia Advocate.

What’s more, from checking Lands and Forestry’s Harvest Plan Map Viewer it becomes apparent that these stands of old forest are exactly what is being targeted on a polygon by polygon basis, Patriquin says.

“From a forester’s point of view, that approach is entirely logical. You want the big volumes. But if you look at it from a landscape perspective it’s a problem, because we’re losing all these older forests over large areas,” he says.

“This loss is even more an issue because those landscapes in southwest Nova Scotia are fragile already. Because of acid rain and the bedrock there, soil in that region has to a high extent been depleted of its calcium content and its base constituents and so on. This is where we’ve lost most of the salmon populations because the waters have become so acidic. And the thing is, the clearcutting just makes it worse because you’re taking up nutrients, and you’re exposing the soil. This also makes recovery much more difficult,” says Patriquin.

Private woodlot owners who want to keep the woodlot for life, and for their children’s lives, do not target the old forest so heavily; they are not the problem. But the way that Big Forestry operates today, it’s going after the profits right now, forget about the future. They’re not planning for future productivity. It’s the the Big Forestry companies who are harvesting and managing Crown lands, following rules set by Lands &Forestry that very much favour logging over other interests.”

“We need to restrict this kind of harvesting, for the sake of biodiversity conservation, and even for future forest production. Many of the clearcut areas are not growing back properly because of physical damage and because the nutrients have been depleted,” says Patriquin.

On the horizon: Plantation forestry

All this is happening while the Lahey report, supposed to bring some high level order and transparency to Nova Scotia’s forestry, continues to collect dust.

“What I am most worried about in the Lahey process at this point, however, is that when L&F finally comes out with its plan to implement the Lahey’s Recommendations, the HPF (High Production Forestry) component will be little altered from the proposals they floated in the Discussion Paper released last February,” Patriquin writes in his post.

Think of HPF as forests tailored to suit the forestry companies, homogeneous forests designated to yield maximum crops for the forest industry.

“Basically, that paper proposes that the most productive, high volume, old forest stands be assigned to the HPF component. Then they can be clearcut followed by spraying/even-aged management or by establishment of plantations and in the next rotation, trees are grown to only 10-12″ dbh (or less) – that’ s a product the sawmills are prepared or are preparing to deal with in the form of “mass timber” once the bigger trees and the easy profits are no more,” Patriquin’s post states.

“We don’t know how Lands and Forestry will respond to its public consultation on that HPF discussion paper last February and that in itself is worrisome, he tells the Nova Scotia Advocate.

“In the meantime, (Big Forestry companies) are doing what they want. In my view, if Lands and Forestry doesn’t drastically reduce the area in which they intend to practice high production forestry it’s going to be worse than it was before, because it essentially allowed them to take out all these purple patches, especially in Southwest Nova Scotia,” he says.

“Meanwhile, we’re reducing the carbon stores like crazy. When in principle, if you wanted forestry to contribute to capturing carbon, what you would do is go into some of the already cut and degraded stands, and put effort into growing a lot of good forests there,” Patriquin explains.

But don’t hold your breath.

“That would help with climate change, but it doesn’t help with the short term profits,” Patriquin says.

David Patriquin closely follows the ups and downs of Nova Scotia’s fragile forest ecologies through Nova Scotia Forest Notes, an excellent website (and newsletter) he maintains. You can follow him on Twitter @JackPine22.

See also: Worse than coal? Biomass not so green, scientists say.

With a special thanks to our generous donors who make publication of the Nova Scotia Advocate possible.

Subscribe to the Nova Scotia Advocate weekly digest and never miss an article again. It’s free!