My dedication to pushing for the National Inquiry into Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls began the moment I realized my sister, Loretta, was indeed missing. It has enveloped nearly every aspect of my life since. Admittedly, at times it has intruded upon other responsibilities such as my studies and personal relationships, I don’t regret making the Inquiry and its success my top priority.

The three, nearly four years, I have committed to the Inquiry pale in comparison to the decades fellow family members and National Family Advisory Circle members have lent to advocating and lobbying for a governmental commitment to ending this national tragedy. Snubbed by the Harper government and governments preceding Harper’s, they forged on to seek justice for their loved ones. Though this heartbreaking narrative continues and our sacred women, girls, transgender and two spirited are still facing violence, we are on the right track to a new path that will ensure safe futures for generations to come.

The National Inquiry into Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls was launched in September 2015. The then five commissioners were presented with data gathered during the pre-Inquiry engagement sessions that spanned a year from coast to coast to coast. Starting from scratch, poring over copious amounts of data, assembling a team of qualified and knowledgeable people

It’s no secret that the Inquiry has faced hurdles in terms of communicating with families, survivors and loved ones affected by this national tragedy. During the pre-Inquiry engagement sessions, people expressed that the Inquiry should not cold call families which predictably created a roadblock in terms of outreach efforts.

Many National Indigenous Organizations (NIO) claim to speak for families and have expressed that there are people who do not have means of contacting the Inquiry. Some families who are lacking a point of contact, or know people who lack a point of contact, have stated that it is the chiefs, presidents and NIO leaders’ responsibility to reach out to their constituents and help facilitate a connection between both parties. Unfortunately, it has become a common experience for families to have never been contacted by the very organizations and governing bodies who claim to represent them.

When communities such as Maskwacis are just gaining access to the internet through efforts made by community member Bruce “Broadband Bruce” Buffalo, disseminating information on how to register with the inquiry is difficult, and registration is made nearly impossible.

The Inquiry’s staff has rectified the breakdown in communication on their end, but concerns about disengaged NIO’s who have had meetings with the Commissioners still echo.

55 families, survivors and loved ones in Whitehorse took part in the first, historical truth-gathering process. Since the hearings, those who volunteered their truths have urged the families, survivors and loved ones in the south to give the Inquiry a chance and asked for patience. The 55 families involved felt heard and some have been waiting decades to tell their truths. The healing that flourishes from this process has been acknowledged by family members of MMIWG2S that hadn’t let a word about their experience slip past their lips in decades.

It’s important to hear the voices of the families who oppose the Inquiry, the commissioners and the process as a whole. However, it has been harmful to families involved in the Inquiry and those who could benefit from it. The damage being done by the mainstream media and NIO’s biased information isn’t just detrimental to the Inquiry itself, but also deters families from seeking an opportunity to heal and gain a sense of closure.

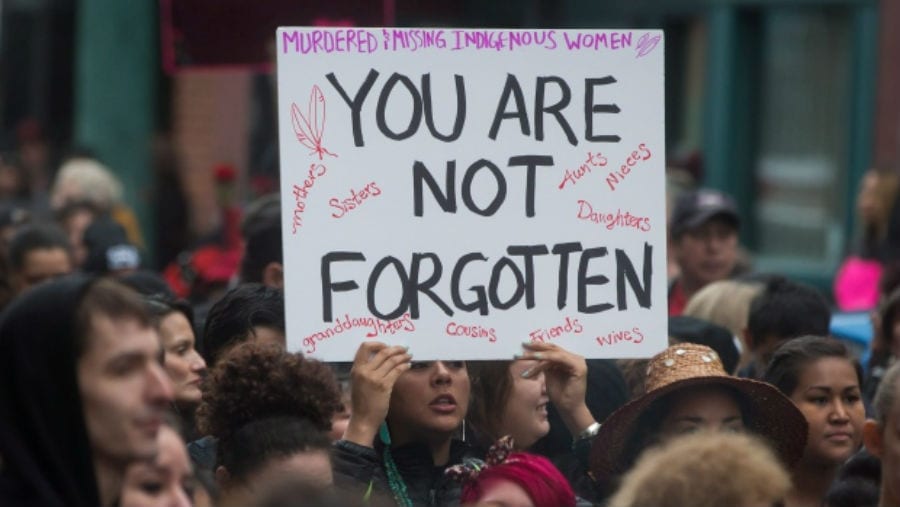

My family and I will be in Halifax this coming October to testify and if it is delayed, then we’ll have to wait. I welcome delays and hiccups in the process if it means the Inquiry is done right and honours the Indigenous women, girls, two-spirit and transgender loved ones we’ve lost. My ego takes a back seat here, because this Inquiry isn’t about me or my lack of patience. It’s about something much bigger. It’s about shifting things in a society so intent on breaking us, so there are no more stolen sisters, daughters, mothers, grandmothers, aunties, cousins, nieces or friends.

Delilah Saunders is an urban Inuk woman from Nunatsiavut. She is a passionate and dedicated advocate for missing and murdered Indigenous women and girls. Her voice for MMIWG was amplified when her sister, Loretta, was silenced far too soon. Delilah was awarded the Amnesty International Ambassador of Conscience Award for her work on the issue and a 10 day hunger strike to oppose the violence inflicted upon Mother Earth regarding the Muskrat Falls hydro-electric dam project in her hometown, Happy Valley – Goose Bay in Labrador.

If you can, please support the Nova Scotia Advocate so that it can continue to cover issues such as poverty, racism, exclusion, workers’ rights and the environment in Nova Scotia. A pay wall is not an option, since it would exclude many readers who don’t have any disposable income at all. We rely entirely on one-time donations and a tiny but mighty group of dedicated monthly sustainers.