KJIPUKTUK (Halifax) – The Mill, by journalist Joan Baxter, is a really good book, and don’t let Kathy Cloutier, the person in charge of communications at Northern Pulp, tell you otherwise. Cloutier famously sent an email to employees urging them to boycott a local bookstore unless it cancelled a book signing by Baxter.

That’s the kind of thing most people with a sense of fair play do not take kindly to, and predictably Cloutier’s scheming made the book exponentially more famous, sales increased beyond the publisher’s wildest dreams, and Northern Pulp was shown to be a bully.

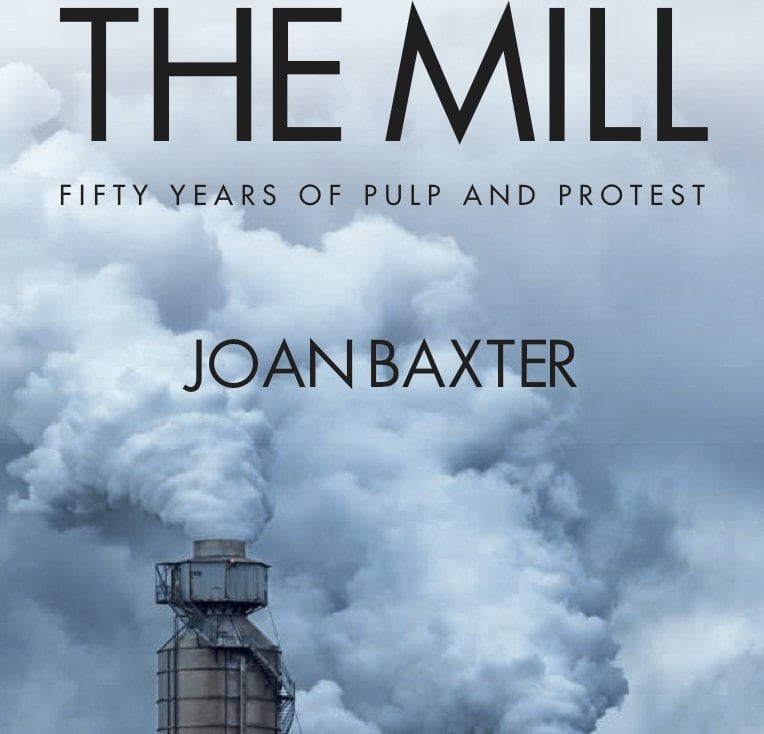

Looking like that bad guy is something that comes naturally to Northern Pulp and its predecessors. Baxter’s meticulously researched book covers a period of 50 years, and it’s all about pollution, environmental racism, and irresponsible clearcutting practices inflicted upon the community and the province by the mill’s owners. Add to that the mill’s habit of pressuring the province for money and more permissive oversight, and at its core that is what Baxter’s book carefully documents.

None of this comes as a surprise. Cutting corner and maximizing profits for owners and shareholders is what these companies are all about. They’re awful. It’s called capitalism.

Equally unsurprising is how so many politicians and bureaucrats support the company in every harmful step it takes, to the detriment of the residents of Pictou County, Pictou Landing First Nation and beyond. When a book covers half a century, and time and again politicians in power and bureaucrats lie, distract, and deny on behalf of the mill while subsidizing the business with millions of dollars, it is hard not to see a pattern.

Among the long list of bureaucratic deceptions and half-lies documented in the book, the betrayal of members of Pictou Landing First Nation by government bureaucrats at the time the Boat Harbour lagoon was in the planning stages stands out as particularly brazen.

Hesitant to give their approval to the creation of the lagoon the chief and a band councillor of the Pictou Landing First Nation were taken to what the bureaucrat claimed was a similar water treatment facility in New Brunswick. The water was clear, there was no smell, and shortly after the Band’s permission was given. But the entire New Brunswick trip was a deception. There was no pulp mill lagoon, what the band members were shown was a domestic sewage disposal site, likely not even operational, and with the water coming from a spring-fed brook.

Speaking of betrayals, the blunt refusal by the Dexter NDP to fund a comprehensive health study of residents in the area was just plain mean. Baxter dedicates most of a chapter to that episode, describing how worries among residents about high rates of cancer and respiratory illnesses have always been prevalent, and how Health minister Maureen MacDonald refused to put these worries to rest. Mind you, she wasn’t the only minister to do so, but hey, isn’t the NDP supposed to be better at those things?

Politicians and mill owners aren’t the sole focus of the book. The book’s subtitle is Fifty years of pulp and protest, and Baxter does a good job profiling these activists and writing about their often very effective efforts.

For every destructive move by the mill there were citizens not only opposing the mill’s plans, but doing so with facts, research, science and logic on their side. Don’t expect new research and new revelations in Baxter’s book, mostly because there is nothing new to uncover. For fifty years citizens (rather than journalists) have been diligently doing their homework, submitting Freedom of Information requests, writing letters to the editor, exposing irresponsible clearcuts, lobbying MLAs and taking the company and the government to court.

And they did so often at high personal costs. We’re talking about individuals who often surrendered large parts of their lives, their privacy and even their health in this fight. Many people lost friends over the mill. With the mill stench continuing unabated, some now wonder if it was worth all that effort and stress, which is a terrible thing to ponder.

Whereas the doings of company and activists are well represented in the book, the voice of workers is notably absent. That’s not Baxter’s fault so much, it’s what happens when most workers and their union leadership turn down interview requests by the author.

There are plenty of hints in the book that there was a time not that long ago that activists and workers at times worked shoulder to shoulder. And why not, workers are residents also, they breathe the same air, they all want their kids to grow up healthy. But something happened, and these days the positions of union and company seem mostly aligned.

Activists that Baxter talks with mostly go out of their way to emphasize that they want the mill to act responsibly, but that they don’t want the mill to close, nor do they want forestry workers to lose their jobs.

But go on Facebook and check out the chatter on some of the environmental group pages and you get a different impression. “What good is it to have a job when the job gives you cancer, you’re better off unemployed”, may get a lot of likes, but it is way too simple, and terribly divisive. Another recent post suggested that the mill be closed and forestry and mill workers find employment in road construction instead, “with all the new federal infrastructure money that is becoming available.” There is a lot of that stuff going on, and not just on Facebook.

Add to that chorus the constant threats, both implied and overt, by the mill’s owners to take their ball and go home if they don’t get their way, and there you have it, the perfect recipe for splitting mill and forestry workers from other community members, a split that benefits no one but the company.

“It has been immensely depressing to see how governments led by all three major political parties have caved to the demands of the mill’s owners and been captured by the pulp industry to make policies to suit them and their profits at the expense of the welfare and best interests of the people who elected them and pay their salaries,” Baxter writes in the book’s epilogue.

Depressing, even heart wrenching at times. But often depressing books are the most important ones. Joan Baxter’s The Mill is one of those.

The Mill – Fifty years of pulp and protest. Joan Baxter. Pottersfield Press

If you can, please support the Nova Scotia Advocate so that it can continue to cover issues such as poverty, racism, exclusion, workers’ rights and the environment in Nova Scotia. A pay wall is not an option, since it would exclude many of our readers who don’t have any disposable income at all. We rely entirely on one-time donations and a tiny but mighty group of dedicated monthly sustainers.

Looking forward to read this book.

Excellent review. Thank you for posting.

It’s an amazing book if only for Baxter’s ability to pull together fifty years’ worth of documents on this boondoggle and make sense of the masses of studies, tangled political shenanigans and sheer number of people involved in the ongoing protests. I keep having to order new copies after giving the book away to slack-jawed friends who find it hard to credit the actions of successive governments and politicians like John Hamm – former premier of the province who helped the mill get mill millions in gov’t grants and received a position as its board chairman once out of office. It’s quite a story.

It is an excellent book that is hard to put down, although I find myself having to take a break from reading it because it’s so upsetting at times. I hope it becomes required reading for students… and I suspect many people employed by the mill will (secretly) be reading it. As Canadians, we are frequently appalled and outraged at large corporations who rape and pillage the resources of other countries (Amazon rainforests, for example) and yet here we are, allowing it in our own backyard!