Reproduced, with permission, from Tony Seed’s excellent blog.

The Venetian navigator Giovanni Caboto (John Cabot), commissioned by Henry VII of England, landed in Newfoundland, on June 24, 1497 believing it to be an island off the coast of Asia and named it New Found Land. [[1] Under the commission of this king to “conquer, occupy, and possess” the lands of “heathens and infidels”, Caboto reconnoitred the Newfoundland coast and also landed on the northern shore of Cape Breton Island in Nova Scotia. [2]

He returned to England on August 6 and took three Mi’kmaq with him, thereby introducing slavery into North America. This may be responsible for his disappearance when he returned to Newfoundland with five ships in 1498. When his ships arrived in northern Cape Breton Island, the Mí’kmaq attacked. Only one ship returned to England, the other four, with Caboto as Captain, never returned.

The royal charter stipulated that King Henry VII would acquire “dominion, title and jurisdiction” over all lands “discovered” by Cabot. It is the foundation upon which the “Dominion of Canada,” as a supposed legal entity, is based. [3] Caboto, sailing from Bristol, a strategic port in the Atlantic slave trade, represented the trading, commercial and shipping houses, such as Lloyds of London and Barclays Bank, who amassed fabulous wealth from the kidnapping of Africans and later financed the neo-colonial confederation of Canada created in 1867 and its railroads from their booty. Caboto returned with stories of the sea teeming with fish. European colonial fishing fleets begin making trips to the Grand Banks every summer.

Initially the Mi’kmaq and Beothuk, however reluctantly at times, treated the visitors as political equals in most important respects and were willing to trade and allow the Europeans to briefly land and dry the cod. In 1500, Caspar de Corte-Real, a slave trader financed by Portugal, captured several Mi’kmaq. He reconnaitred the coast of Newfoundland and Labrador, kidnapping 57 “man slaves” (Boethuks) to be sold to finance the cost of the expedition. His belief that Nitassinan was teeming with potential captives lead to it being called Labrador, “the source of labour material.” His ship was lost at sea, although two of his ships did return to Portugal. By 1504 French Bretons were fishing off the coast of Míkmáki country. In 1507 Norman fishermen brought another seven Boethuk prisoners to France. This affected all future relations between the Beothuk and the fishermen.

The development of the Atlantic fisheries, a seemingly inexhaustible source of cheap protein, is inextricably linked to the Atlantic Slave Trade which fertilizes the development of the capitalist system and consolidation of national states in Europe. It later forms the basis of the wealth of leading families in colonial Nova Scotia and New England.

On June 11, 1578 Sir Humphrey Gylberte (Sir Humphrey Gilbert) received Letters Patent for Newfoundland. He was a big colonizer through English colonial plantations of Gaelic Ireland with his half-brother Sir Walter Raleigh. On August 5, 1583, Gilbert received a grant from Queen Elizabeth I and attempted to settle a colony in Newfoundland. He failed due to the lack of resources to withstand the cold and starvation. He lays formal claim to Newfoundland and the Maritimes. France, citing Jacques Cartier’s voyage and the doctrine of “discovery”, opposed the claim. He drowned in a storm on 9 September off Sable Island in Canada’s first recorded marine disaster (sic).

In 1585, Sir Walter Raleigh first attempted to settle a plantation colony in Roanoke, which is part of the land called Virginia, in honour of Queen Elizabeth, who was referred to as the Virgin Queen. Roanoke is actually an island off the coast of North Carolina.

The King or Queen issue royal Charters by the authority of The Royal Prerogative, which continues to date in the unrepresentative Westminster parliamentary system imposed on Canada in 1867. Charters are legal documents that decreed grants, particularly land grants, by the sovereign to his or her subjects.

The power and authority of the King and Queen are almost absolute, as the following commentary by Blackstone shows:

“And, first, the law ascribes to the king the attribute of sovereignty, or pre-eminence. He is said to have imperial dignity, and in charters before the conquest is frequently styled basileus and imperator, the titles respectively assumed by the emperors of the east and west. His realm is declared to be an empire, and his crown imperial, by many acts of parliament, particularly the statutes 24 Hen. VIII. c. 12. and 25 Hen. VIII. c. 28; which at the same time declare the king to be the supreme head of the realm in matters both civil and ecclesiastical, and of consequence inferior to no man upon earth, dependent on no man, accountable to no man”.

By 1586, typhus was spread amongst the already weakened Mí’kmaq population, which yielded yet more lives to the deadly epidemic brought to the Maritimes by the Europeans.

On July 11, 1596 Queen Elizabeth I of England issued a proclamation saying that “all Negroes and blackamores” are to be arrested and expelled from the kingdom – although she herself has an African entertainer at court and becomes a lead investor in the Royal Africa Company, based in London:

“there are of late divers blackmoores brought into this realme, of which kinde of people there are allready here to manie … Her Majesty’s pleasure therefore ys that those kinde of people should be sent forth of the lande.”

Every monarch and their family from Elizabeth Tudor onwards are financiers and beneficiaries of this trade in human flesh. By the 18th century Britain was the world’s leading trafficker. About half of all enslaved Africans are transported in British ships. Eighty per cent of Britain’s income was connected with these activities.

On the quincentennial anniversary of Caboto’s landfall, Queen Elizabeth II, sovereign of Canada, toured the country in a official celebration sponsored by the Harper government. According to her, Caboto’s landfall “represented the geographical and intellectual beginning of modern North America…” – the Eurocentric Discovery Doctrine. [4] As is well known, in Newfoundland the genocide of the Beothuk Indians occurred. Queen Elizabeth was right – the pattern was set there. So far as the Indigenous peoples are concerned, of course, the pattern set was genocide.

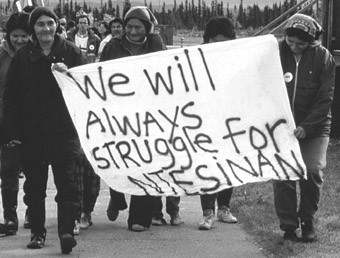

When Queen Elizabeth II visited Sheshatshiu in Labrador, the reception was “mixed”, as “protestors waved placards denouncing her visit.”

The Canadian Press reported “Aboriginals have said it’s insulting to celebrate explorer John Cabot’s arrival in North America because of the devastating impact colonization has had on them… The Queen’s visit to this riverside community (Bonavista) of 1,200 stood out on other levels. Dogs meandered about her sand-covered route and there was not a Union Jack or Maple Leaf in sight. There was none of the gushing witnessed at previous events this week…” [5]

In Sheshatshiu, Innu community leaders presented her on June 26, 1997 with a letter that read in part:

“The history of colonization here has been lamentable and has severely demoralized our People. They turn now to drink and self-destruction. We have the highest rate of suicide in North America. Children as young as 12 have taken their own life recently. We feel powerless to prevent the massive mining projects now planned and many of us are driven into discussing mere financial compensation, even though we know that the mines and hydroelectric dams will destroy our land and our culture and that money will not save us.

“The Labrador part of Nitassinan was claimed as British soil until very recently (1949), when without consulting us, your government ceded it to Canada. We have never, however, signed any treaty with either Great Britain or Canada. Nor have we ever given up our right to self-determination.

“The fact that we have become financially dependent on the state which violates our rights is a reflection of our desperate circumstances. It does not mean that we acquiesce in those violations.

“We have been treated as non-People, with no more rights than the caribou on which we depend and which are now themselves being threatened by NATO war exercises and other so-called development. In spite of this, we remain a People in the fullest sense of the word. We have not given up, and we are now looking to rebuild our pride and self esteem.” [6]

On October 12, 2013 the Mi’kmaq Warriors Society and Elsipogtog First Nation in New Brunswick, who were blockading a Texas monopoly’s fracking operation, demanded as was their right that the government “produce documents proving Cabot’s Doctrine of Discovery.”

The just demands of the Indigenous peoples for the recognition of their rights are not a “special interest” but an issue facing the entire polity which can only be resolved through modern arrangements that uphold rights on the basis that they are inviolable and belong to people by virtue of their being.

Notes

The main source is “Mi’kmaq & First Nations Timeline (75,000 BC – 2000 AD): Eclipse & Enlightenment,” Tony Seed and the editors of Shunpiking Magazine, Halifax, 2000. With a file from Richard Sanders.

[1] An excerpt from the Report of the Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples:

First contacts between Aboriginal peoples and Europeans were sporadic and apparently occurred about a thousand years ago when Norsemen proceeding from Iceland and Greenland are believed to have voyaged to the coast of North America. There is archaeological evidence of a settlement having been established at L’Anse aux Meadows on the northern peninsula of what is now Newfoundland. Accounts of these early voyages and of visits to the coast of Labrador are found in many of the Norse sagas. They mention contact with the indigenous inhabitants who, on the island of Newfoundland, were likely to have been the Beothuk people, and on the Labrador coast, the Innu.

These early Norse voyages are believed to have continued until the 1340s, and to have included visits to Arctic areas such as Ellesmere and Baffin Island where the Norse would have encountered Inuit. Inuit legends appear to support Norse sagas on this score. The people who established the L’Anse aux Meadows settlement were agriculturalists, although their initial economic base is thought to have centred on the export of wood to Greenland as well as trade in furs. Conflict with Aboriginal people likely occurred relatively soon after the colony was established. Thus, within a few years of their arrival, the Norse appear to have abandoned the settlement and with it the first European colonial experiment in North America.

Further intermittent commercial contacts ensued with other Europeans, as sailors of Basque, English, French and other nationalities came in search of natural resources such as timber, fish, furs, whale, walrus and polar bear.

Report of the Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples, Volume 1 – Looking Forward, Looking Back, October 1996

[2] Caboto came armed with assumptions similar to those of the Spanish colonialists further south. Thus, the letters patent issued to John Cabot by King Henry VII gave the explorer instructions to seize the lands and population centres of the territories “newely founde” in order to prevent other, competing European nations from doing the same:

“And that the aforesaid John and his sonnes…may subdue, occupie, and possesse, all such townes, cities, castles, and yles, of them founde, which they can subdue, occupie and possesse, as our vassailes and lieutenantes, getting vnto vs the rule, title, and iurisdiction of the same villages, townes, castles and firme lands so founde…”

[3] While the King gave Cabot the “full and free authority, faculty and power” to “find, discover and investigate whatsoever islands, countries, regions or provinces of heathens and infidels,” there was an important caveat, as Richard Sanders points out. Cabot’s license only applied to lands that “were unknown to all Christians.” With this imperial licence to wage an unending, plunderous war against non-Christians, Cabot and “his sons or their heirs and deputies” gained the exclusive right to rule as the King’s “vassals and governors, lieutenants and deputies.” In exchange, they were “bounden and under obligation” to pay King Henry “either in goods or money, the fifth part [20 per cent] of the whole capital gained.” The “capital” was defined as “all the fruits, profits, emoluments [earnings], commodities, gains and revenues.”

“John Cabot and Britain’s Fictitious Claim on Canada: Finding our National Origins in a Royal Licence to Conquer,” Richard Sanders, Press for Conversion!, Magazine of the Coalition to Oppose the Arms Trade magazine, No. 69

http://coat.ncf.ca/P4C/69/69_4-7.htm

[4] Vancouver Province, 25 June 1997.

[5] “Labrador protest: Royal visitors get mixed reception,” Michelle McAfee – Canadian Press, Victoria Times-Colonist, p. A10, Friday, June 27, 1997.

http://sisis.nativeweb.org/clark/jun27que.html

[6] http://www.hartford-hwp.com/archives/41/052.html

For Your Information

This extract from the letters patent issued to John Cabot and other instructions given to voyagers to the “new world,” illustrates how Great Britain and France initially had far-reaching plans for imperialist adventures in North America that took little account of the rights of the Aboriginal inhabitants.

The Letters Patents of King Henry the Seventh Granted unto John Cabot and his Three Sonnes, Lewis, Sebastian and Sancius for the the Discouerie of New and Unknowen Lands; 5 March 1498. An excerpt:

“Henry, by the grace of God, king of England and France, and lord of Ireland, to all to whom these presents shall come, Greeting. Be it knowen that we haue giuen and granted, and by these presents do giue and grant for vs and our heiress to our welbeloued Iohn Cabot citizen of Venice, to Lewis, Sebastian, and Santius, sonnes of the sayd Iohn, and to the heires of them, and euery of them, and their deputies, full and free authority, leaue, and power to saile to all parts, countreys, and seas of the East, of the West, and of the North, vnder our banners and ensignes, with fine ships of what burthen or quantity soeuer they be, and as many mariners or men as they will haue with them in the sayd ships, vpon their owne proper costs and charges, to seeke out, discouer, and finde whatsoever isles, countreys, regions or prouinces of the heathen and infidels whatsoeuer they be, and in what part of the world soeuer they be, which before this time haue bene vnknowen to all Christians; we haue granted to them, and also to euery of them, the heires of them, and euery of them, and their deputies, and haue giuen them licence to set vp our banners and ensignes in euery village, towns, castle, isle, or maine land of them newly found. And’that the aforesayd Iohn and his sonnes, or their heires and assignee may subdue, occupy and possesse all such townes, cities, castles and isles of them found, which they can subdue, occupy and possesse, as our vassals, and lieutenants, getting vnto vs the rule, title, and jurisdiction of the same villages, townes, castles, & firme land so found. Witnesse our selfe at Westminister, the fifth day of March, In the eleventh yeere of our reigne.-

Why “The Dominion of Canada”?

By Tonya Gonnella Frichner

The Old World idea of property was well expressed by the Latin word dominium: from dominus, and the Sanskrit domanus (he who subdues). Dominus carries the same principal meaning (one who has subdued), and is extended naturally to signify ‘master, possessor, lord, proprietor, owner.’

Dominium takes from dominus the sense of ‘absolute ownership’ with a special legal meaning of “property, right of ownership” (Lewis and Short, A Latin Dictionary, 1969).

Dominatio extends the word into “rule, dominium,” and … “with an odious secondary meaning, unrestricted power, absolute dominium, lordship, tyranny, despotism.” Political power grown from property — dominium — was, in effect, domination. (William Brandon, New Worlds for Old, 1986, p.121.).

State claims and assertions of ‘dominion’ and ‘sovereignty over’ indigenous peoples and their lands, territories and resources trace to these dire meanings, handed down from the days of the Roman Empire, and to a history of dehumanization of indigenous peoples. This is at the root of indigenous peoples’ human rights issues today.

Source: Excerpt, “Impact on Indigenous Peoples of the International Legal construct known as the Doctrine of Discovery, which has served as the Foundation of the Violation of their Human Rights,” UN Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issues, February 3, 2010.

With a special thanks to our generous donors who make publication of the Nova Scotia Advocate possible.

Subscribe to the Nova Scotia Advocate weekly digest and never miss an article again. It’s free!