(from a chapter I wrote, Rape at Saint Mary’s University, published in Sexual Violence at Canadian Universities: Activism, Institutional Responses and Strategies for Change, edited by Elizabeth Quinlan, Andrea Quinlan, Curtis Fogel, and Gail Taylor. Wilfred Laurier University Press, Waterloo, Ont. 2017).

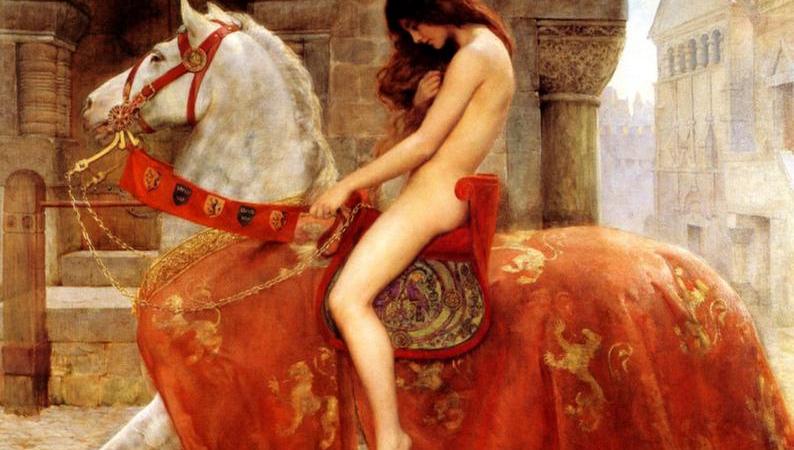

KJIPUKTUK (Halifax) – On the wall in my office is a copy of a painting of Lady Godiva, by the British pre-Raphaelite artist, John Collier. Painted in 1898, the picture depicts a beautiful dark- haired young woman riding on a white horse through a street in medieval Coventry. Legend has it that the peasants on the Earl of Mercia’s estates near Coventry, England could no longer afford to pay the high taxes demanded by Lord Leofric. The peasants asked Godiva, Leofric’s wife to intercede. The lord agreed to lower the taxes on the condition that Godiva had to ride naked through the busy town marketplace. She did – the painting shows her in profile – her long hair covering all but her legs.

Fast-forward 900 years to the mid-twentieth century. Women students at many university campuses housing an engineering school were witnesses to the “Lady Godiva Ride.” It varied, depending on the conditions and the weather, but the impact was the same. For example at the University of Saskatchewan, engineering students got a horse and paraded a half-clothed co-ed around “the Bowl” in the centre of the campus, in what was known as Lady Godiva Ride. At the University of British Columbia, up to 1990, a naked woman cloaked in an academic robe sat on a horse that was led through the campus — to howls of fellow engineering students.

On December 6, 1989, 14 women engineering students were massacred at l’Ecole Polytechnique in Montreal. Twenty-five-year-old , unemployed Marc Lepine gunned down thte women before taking his own life. A short time later, police discovered a letter from Lepine stating he “hated feminists”. Lepine had also kept an “annex”, a written list of 19 “radical feminists” (his words) whom he planned to kill. The list included names of women journalists, politicians and even a police officer. In his suicide note, Lepine wrote that he wanted to “send the feminists who have always ruined my life to their maker.”

Across Canada the night of the massacre in Montreal, thousands of women (and some men) honoured the murdered women by protesting violence against women. I attended a candlelight vigil at the University of Saskatchewan. Despite Lepine’s suicide note, the majority of journalists and politicians insisted the killer was simply mentally ill.

Was Marc Lepine a mad man?

February 1990 , barely two months later, Engineering Week was celebrated at universities across Canada. CBC-TV’s national news program Sunday Report produced a three-minute news item about the Godiva ride, in the wake of the Montreal Massacre. Reporter Karen Webb conceded in that because 3% of professional engineers were women, and only 10% of engineering students were female, sexism might play a role in the Godiva ride. Webb interviewed the University of British Columbia’s engineering student council president, who wanted to maintain the tradition of the Godiva ride on campus. He lamented the loss of a school ritual and good fun, if the ride were to be cancelled. At the University of Saskatchewan, Webb interviewed one male engineering student who said nothing needed to change as the Godiva ride would die out eventually.

The engineering students interviewed did not want to link the Godiva ride to the Montreal Massacre. Journalist Karen Webb was, like many of her male colleagues, ambivalent about what drove Lepine ended her TV report by suggesting that he was less than sane: “Many engineering students say that they resent being put under a microscope just because a madman chose women in their faculty as his targets.”

While many in the mainstream media called Lepine a madman (but interesting, never a terrorist, as they might have done today), Canadian feminists saw that something more sinister and more systemic had happened.

Leading Quebec journalist Francine Pelletier, whose name appeared on Lépine’s “annex” of feminists, claimed that the massacre was a political act. According to her, it was not simply about women but about women who were threatening men’s power by entering male professions:

“If he had wanted to target women, he would have gone to a nursing school. He was targeting women who had the audacity to want to do a man’s job.” Francine Pelletier

from “What was the impact of the Montreal Massacre?Remembering from Montreal at feminist gathering,” by Judy Rebick in Rabble, 2009

The registrar at L’Ecole Polytechnique confirmed this when asked why Marc Lepine had never been admitted to the school, despite having applied twice:

“I was surprised by the way he spoke about women, about how they were taking over the job market. He thought there was something wrong with that.”

from H. Gagne and M Lepine (2008) in Aftermath, Toronto: Viking Canada

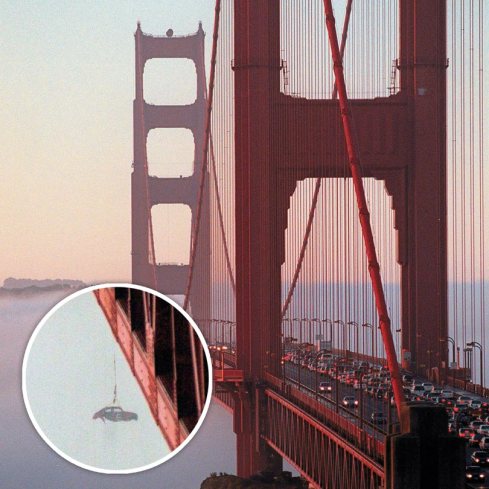

It could be said that the Montreal Massacre ended the Godiva rides. In the 1990s, across the country, engineering school students returned to doing other practical jokes, such as dangling Volkswagen Beetle cars from the Golden Gate Bridge.

At the same time more women started to enter professions such as law, pharmacy, and medicine. The numbers of women entering engineering school edged up, though they fared less well than at other professional schools. Recent Canadian statistics collected by Engineers Canada reveal that women are fewer than 18% of total undergraduate engineering school enrollments, with a similar percentage in Nova Scotia universities. That number has not increased appreciably in 20 years.

References for all quotations and more available on request.

Judy Haiven is on the steering committee of Equity Watch, an organization that fights discrimination, bullying and racism in the workplace. Contact her at equitywatchns@gmail.com

With a special thanks to our generous donors who make publication of the Nova Scotia Advocate possible.

Subscribe to the Nova Scotia Advocate weekly digest and never miss an article again. It’s free!