KJIPUKTUK (Halifax) – There is a name for police stopping and questioning people when no particular offence is being investigated. It’s called carding. Yet Halifax police calls it street checks, and media outlets duly follow suit.

That’s the wrong term, for two reasons.

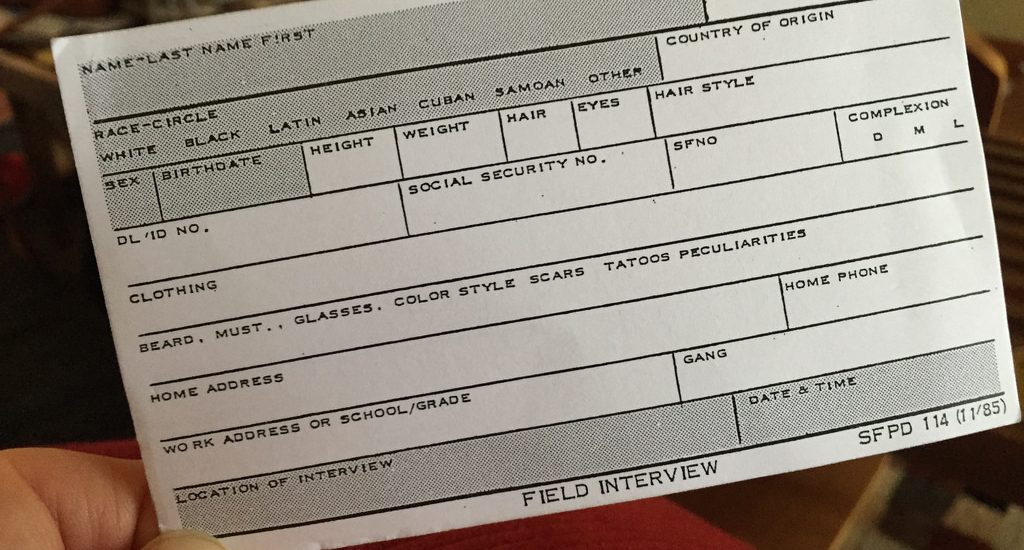

First of all, street checks is not what is happening, or at least it’s not the whole story. In Ontario and elsewhere it’s called carding, because not only does the police engage a person in conversation, the who, where, what and when of the encounter gets documented (originally on a card), and stored in a database.

As in Ontario, so in Halifax.

Between 2005 and 2016 Halifax Regional Police collected 98,551 entity records, representing 36,652 unique individuals, reports Dr. Chris Giacomantonio, Research Coordinator with HRP. As widely reported, a vastly disproportionate number of these records are about Black people.

Secondly, throughout its controversial history in Ontario, particularly in Toronto, the issues around carding have been thoroughly discussed, by Black activists, human rights lawyers, by politicians, columnists, and citizens.

Calling the practice street checks rather than carding ignores that discussion, suggesting that what is happening here in Halifax is somehow unique and we need to start our thinking about this practice from scratch.

Yet in Ontario, as a result of that discussion, the provincial government has already defined various obvious constraints on carding that Halifax police is reluctant to even consider.

For instance, police there must tell people they have a right not to talk with them, and refusing to co-operate or walking away cannot then be used as reasons to compel information.

Police must also explain why the person is questioned, and provide their batch number and name. They must do this all the time, not just when challenged to do so.

As well, in Ontario police must issue a yearly report containing the kind of information CBC in Nova Scotia had to dig out using Freedom of Information legislation.

But clearly, even with these new rules of engagement loopholes remain for police to exploit.

Halifax lawyer David Fraser, in an interview with Rebecca Dingwell in the Coast, rightly calls the practice of carding coercive and random.

“Every one of these interactions is a collection of personal information against somebody’s will and without their true, willing consent,” he says.

So what about the data stored on a HRP server?

Again the Ontario discussion can inform what we decide to do in Halifax.

“There is no question what needs to happen to this data: it must be eliminated from the Toronto Police Service and anywhere else it exists and this must happen immediately,” write Sandy Hudson and Yusra Khogali, co-founders of Black Lives Matter Toronto, in the Toronto Star.

“There is no reason data collected through the unjust surveillance and documentation of people in our communities should remain on file. No one else should bear the sometimes fatal consequences of this type of systemic discrimination by law enforcement,” they say.

I agree. We don’t need that tainted database. We don’t need to subject an entire community to yet another form of racist violence.

We should call it carding, and it should stop entirely.

If you have a bit of money to spare, please support the Nova Scotia Advocate. It will allow us to continue to cover issues such as poverty, racism, exclusion, workers’ rights and the environment in Nova Scotia.