Racial profiling has lately been in the news in Nova Scotia. In September, Dr. Lynn Jones, a well-known champion of civil rights and a labour leader, was stopped by police while out with friends watching deer. Someone had called the police to report “suspicious people” in the neighbourhood. To add insult to injury, Jones was stopped in a historically black community in the town of Truro known as “The Marsh,” the area in which she grew up. Following this experience, she put together a community meeting, leading town council to pass a motion that will work to improve relations between black residents and the municipal government.

Then, on October 21, the chief of the Halifax Regional Police announced that the force will formally apologize for the practice of “street checks,” which has disproportionately affected black people in the city and its suburbs. This followed a provincial ban on the practice in April, which itself followed a report by University of Toronto criminology professor, Scott Wortley. His report found that black people were six times more likely to be stopped in the so-called “random” checks than white people in Halifax. That prompted an independent legal review, which found that the checks were illegal.

African Nova Scotians had been agitating for a ban for many months. Derico Symonds, who organized a march to support a ban in the spring, said to CBC News that it was not lost on him that it took two reports from two white men to finally get the practice banned: “And so that it took this amount of effort is absolutely disappointing. If folks don’t get their driveway shovelled in Halifax it’s an uproar and there’s immediate action. But then when we have something such as this with a 180 page report that says that the practice is racist and we know that it is, it takes several efforts from several different people over several months to actually have the action that we were asking for.” Symonds and other advocates, Trayvone Clayton, Shevy Price, and Kate Macdonald, had earlier walked away from a working group formed following the release of the Wortley report after it refused to consider an outright ban on checks. Unfortunately, activists complain that checks have continued even after the ban.

As Symonds expressed, a great deal of frustration permeated the discussion around this issue, even after this apparent win for civil rights. When the report was released, Robert Wright, chair of the African Nova Scotia Decade for African Descent Coalition’s justice committee, The Coast said that he found it hard to hear about the supposed shock of leaders who expressed surprise at the findings of the Wortley report: “‘How do you get to be the head of the police commission and be horrified by the stories people tell about their racist interactions with the police?’ Wright asks. “Do you not know that people suffer daily indignity in their encounters with the police?’” These events, and the responses by activists to them, had me thinking about the nature of disbelief. Why do white people persist in disbelieving the experiences of racialized peoples in this province, or in Canada more generally?

It also made me think about the many consumer affairs stories that we hear, such as the work done by CBC’s “Go Public” series. When people complain about cars with persistent dangerous mechanical failures, or bad service from airlines, the average person is automatically sympathetic. In general, we do not doubt these events have happened. This is because when many people, all with something obvious in common, report the same experience, those experiences become credible. Yet a similar automatic belief in experiences of racism does not seem to exist among white people. Why is this? Perhaps it is because when someone reports that they were lied to by telecom customer service agents, we (I’m now using “we” to identify white people) can assign blame to a greedy, faraway, corporate elite. But when someone details their life with racism while shopping for groceries, working as a bus driver, furniture salesperson, firefighter, janitor, or in their interactions with police, then the culprits become us, and our neighbours, friends, and relatives. It is deeply uncomfortable to admit that while only a minority of us are actual white supremacists, white supremacy lives in all of us.[1] It becomes easier to question and doubt. After all, haven’t we all had a troublesome co-worker prone to lying and drama? What if the shopper did seem suspicious for credible reasons? Perhaps race had nothing to do with it, and how would we feel if we were being unfairly charged with racism? And suddenly, in our imaginations, we become the victims.

Yet as white people, we usually do not have to look very far to find our own culpability, or that of personal acquaintances. I was standing in line at the grocery store when I overheard the man behind me say to his friend, “well, some people might say that’s racist, but just because it’s racist, it doesn’t mean it’s not true,” followed by laughter. I was about to turn around and counter that by definition if something is racist it cannot be true (thus cementing my status as the most popular person in the grocery store), when my husband, who had not heard the previous exchange, said, “oh, hi [name]!” It was a close relative. I shut my mouth.

Fortunately, historians are in a good position to counteract this epidemic of disbelief even if they do not personally study histories of race and racism. And it’s not because, as some observers feel, historians are furious leftists on a quest to make history as depressing and boring as possible. It is because they fundamentally believe historical context matters, and that events in the past influence the present. While others may easily rattle off the platitude that “that was then, this is now,” historians cannot. Now and then are linked together by complex and enduring webs that bind together yesterday and today’s societies, economies, and polities. And for anyone with even a passing knowledge of the history of Indigenous people and racialized minorities in Canada, the history of discrimination, violence, persecution, segregation, as well as activism and resistance, is inescapable. This has been shown through the important scholarship of many historians in this country, work that has often been done by Indigenous people and people of colour.

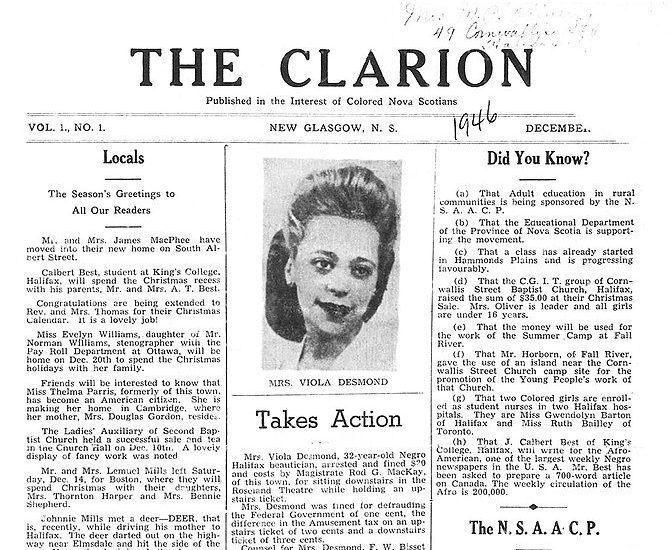

These factors could not be more visible than when examining the histories of those of African descent in Nova Scotia, going back to slavery in the French and British colonial regimes, violence in colonial Shelburne, the segregation of historically black communities, and of course, the fate of Africville. I recently saw a presentation by an Atlantic Studies M.A. student at Saint Mary’s University, Sawyer Carnegie, who is working on a thesis project about historical black newspapers in Nova Scotia. She drew my attention to the fact that the Nova Scotia Archives has digitized copies of some of these newspapers, including The Clarion, founded and edited by Carrie Best. Though many now know of Viola Desmond’s story thanks to a new $10 bill and Heritage Minute, Best’s challenge to segregation in the same New Glasgow theatre preceded Desmond’s by several years.

She had visited the theatre to ask for the policy of confining black people to the balcony to be changed, and when that failed, she issued this challenge to its owner in a letter:

As I am too tired to come to the theatre tonight, I respectfully request you, Sir, to instruct your employees to sell me the ticket I wish when I next come to the theatre or I shall make public every statement made to me by you and your help; of negroes being dirty, smelly, etc. … I speak today for no family but my own and if you wish a public controversy both pro and con as to whether you have the power of a dictator to decide in a British town who is a citizen and who isn’t, you can have it.”[2]

The next time she went to the theatre, the staff would only sell her balcony tickets. She left them on the counter and she and her son sat in the main part of the theatre, then were roughly ejected by the police. Though Best launched a civil lawsuit against the theatre, she lost the case.[3] But later she and her newspaper gave extensive attention to Desmond’s case, which went to the Supreme Court in Nova Scotia, also unsuccessfully. Despite the legal loss, Best claimed a moral victory, writing, “The Clarion feels that the reason for the decision lies in the manner the case was presented to the Court,” but that, “We feel that owners and managers of places of amusement will now realize that such practices are recognized by those in authority for what they are—cowardly devises to persecute innocent people because of their outmoded racial biases.”[4]

A paradoxical expression of fatigue and energy permeates Best’s writing about the theatre, which strongly reminds me of the response of activists dealing with issues of racial profiling today. Fatigue that such an obvious injustice persisted and that the legal system seemed unable to right the wrong, with a continuing energy borne from anger and a steely backbone. Though the theatre has become the best known symbol of Jim Crow-style segregation in Nova Scotia, it was hardly the only example. James St. G. Walker extensively interviewed his friend and activist (and brother to Lynn), Burnley “Rocky” Jones, for his biography, published after Rocky’s death. In it, Jones describes several instances of racism and segregation in his hometown of Truro, including being barred from playing pool at a local establishment, a humiliating experience for the young teenager.[5] For every story told about segregation in the province, there are countless that have gone unrecorded.

Recently, Kirk Johnson, the famous Nova Scotian boxer who in 2003 won a victory with the Nova Scotia Human Rights Commission against police, gave an interview to CBC Halifax’s Information Morning. His case involved repeated stops while driving, and one time the seizure, of his vehicle by police. I was surprised (there’s that white surprise again) that this sixteen-year old victory did not give him a magic spell that warded off traffic stops by police. Indeed, he said he continues to be occasionally stopped when he visits his home province. He had recently been pulled over for accidentally driving 50km in a 30km school zone, but that, he said, he didn’t mind, because he was doing something wrong and the police officer was polite to him. While this sounded reasonable, I could not help but think that despite the many times I am sure I have accidentally sped in school zones, I have never once been pulled over by police. In fact, I have never once been pulled over by police while I was driving outside of inspection or drunk driving checks, period. I’m a cautious driver, but then, I’m guessing Kirk Johnson is pretty cautious by now too. Though I will not say that as a woman I always feel at ease in this world, there are countless situations where my skin colour has allowed me to move through it at ease, all while not even realizing it was happening.

As a historian, I simply cannot continue to be surprised by racism in this province, nor surprised by my own ease in it as a descendant of the white settler class. I have no choice but to see them as two sides of the same coin, and borne of a long social, political, and legal history that has unfairly subjugated African Nova Scotians, the Mi’kmaq, and other racialized people, for centuries. And if I do nothing else (though clearly I can and should do more, including supporting the activism of black Nova Scotians and others) this is something I can convey to my white friends, relatives, and neighbours. If they express disbelief, I can tell them about Carrie Best. If they try to tell me that was a long time ago, I can explain that a young black man endured racial slurs until being shot by a nail gun while working for a New Glasgow construction firm just a year ago, and that we cannot see such events in isolation from their historical context. And I can be open and honest about the way that racism inhabits and has inhabited me, and my continuing efforts to reckon with it. How about the time I asked only the racialized students in my group in an undergraduate class “where are you from?” What harms have I caused that I cannot even remember in my obliviousness?

In the finest tradition of white women liberals, I will now quote Oprah, who herself is fond of quoting the late author Maya Angelou: “when you know better, you do better.” So far, knowing better has not achieved enough for equality in Nova Scotia, because knowing the facts and believing them seem to be two separate cognitive acts. It is time for white people to not just know better, but believe better, and act on that belief. As historians, this is a social good that we are uniquely positioned to affirm.

Jill Campbell-Miller is a Postdoctoral Fellow in History at Carleton University.

This article was originally published on ActiveHistory.ca, a website that connects the work of historians with the wider public and the importance of the past to current events. Republished with the author’s kind permission.

Notes

[1] This was an idea expressed by Stephen Brookfield in an interview with NS Information Morning, October 19. 2019. https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/nova-scotia/programs/informationmorningns/professor-on-how-to-recognise-systemic-racism-1.5325777.

[2] Constance Backhouse, “‘I Was Unable to Identify with Topsy’: Carrie M. Best’s Struggle Against Racial Segregation in Nova Scotia, 1942,” Atlantis 22, no. 2 (Spring 1998), 19.

[3] Backhouse, “‘I was Unable to Identify with Topsy,’” 22-23.

[4] “The Desmond Case,” The Clarion, April 15, 1947, 2.

[5] Burnley “Rocky” Jones and James W. St. G. Walker, Burnley “Rocky” Jones Revolutionary (Halifax: Fernwood Publishing, 2016), 27-28.

With a special thanks to our generous donors who make publication of the Nova Scotia Advocate possible.

Subscribe to the Nova Scotia Advocate weekly digest and never miss an article again. It’s free!