KJIPUKTUK (Halifax) – I have often discussed how the provincial government can do a better job of bringing resources from actually autistic people into the classroom. Today I will explore this in more detail.

Specifically, I want to take a look at the P-12 Education section of Autism Nova Scotia’s Choosing Now report. Released in April 2017, it identifies various areas where autistic people need more support throughout their lives.

I will review three main ideas: what “autism-specific knowledge and skills” really means; appropriate resources for “autism consultants” to have; and what an “autism centre of excellence” should look like. The main goal of the report’s P-12 education section is inclusion, and inclusion benefits all students, neurodivergent or not.

Autism-specific knowledge and skills

One issue raised by the report is: “Overall knowledge of ASD within School Boards (and individual schools) is well below optimal, even among more highly trained support staff and new teachers entering the system.”

Many autistic people, myself included, would agree 100%. To address this issue, recommendation number 13 reads as follows:

“Ensure that education professionals and support workers have strong autism-specific knowledge and skills that optimize learning for all students with ASD in the school system.”

Sounds good on the face of it, but what exactly does “autism-specific knowledge and skills” mean? The report does not include a working definition of this.

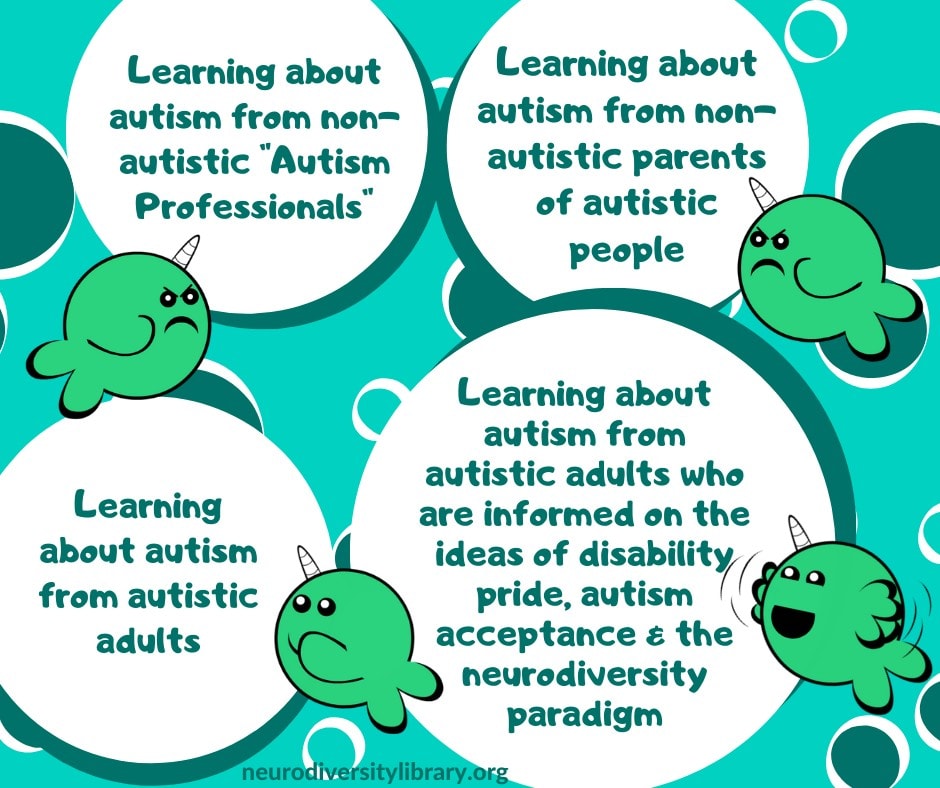

At this time autism-specific knowledge and skills are typically developed and sourced from non-autistic professionals. Autistic people are significantly impacted by policy and program decisions made for and about them, but they are often under-represented directly in those decision making processes. Autistic people are key stakeholders whose lived experience can have a substantial influence on what constitutes autism-specific knowledge

It’s not just the anecdotal accounts of numerous autistic people, although those are certainly helpful. There are also resources created by autistic people that are rooted in decades of lived experience and inspired by numerous autistic people who have worked to inform non-autistic parents and professionals.

Resources for individuals, families, and autism consultants

Choosing Now points out that all school boards (or Regional Centres of Education) have staff to support autistic children’s learning and development, such as autism consultants or specialists, school psychologists, speech-language pathologists, and special education consultants. But it also acknowledges that they face critical staffing shortages in those same positions.

Since the report’s publication, the government has hired some more inclusive education staff, but much more is needed.

It is important that the resources these people have access to are sourced primarily from actually autistic and other neurodivergent people and informed by the ideas of disability justice, autism acceptance, and the neurodiversity paradigm.

So what would be some good resources to have?

For starters, they could access anything and everything from Foundations for Divergent Minds (FDM), which I have written about before.

See also: For autistic children government programs aren’t the only option

FDM offers a six-lesson training course for parents, which provides practical guidance on how they can set up their home to meet their neurodivergent children’s needs in terms of sensory integration, executive functioning, communication, social interaction and emotional regulation.

FDM also has a 12-lesson course for professionals such as teachers, therapists and counselors, which encourages them to think differently about how to support neurodivergent children. The course includes discussions on disability history, the neurodiversity paradigm, autistic traits, and goals toward self-advocacy and self-determination. Both courses include a video for each lesson, a discussion question and required assignments to complete on a weekly schedule. The training courses are not free, but payment plans and scholarship options are available.

In addition, FDM is currently exploring the development of a “Reimagined Home Kit”. They plan to include with the kit sensory tools, routine cards, basic communication cards, social interaction bracelets and emotion cards, all to support autistic and other neurodivergent children at home, at school and in the community.

Another excellent resource is United for Communication Choice. This is a grassroots volunteer group organized by disabled people and their families to support the rights of disabled people to choose the methods of communication that work best for them. Resources available on their website include numerous peer-reviewed research articles, videos of people learning to communicate with alternative methods, and award-winning documentaries.

Foundations for Divergent Minds and United for Communication Choice are two of the best resources that utilize a neurodiversity paradigm-informed approach that honours the uniqueness of the lived experience of autistic and other disabled people.

Autism centres of excellence

Recommendation number 17 of the Choosing Now report reads as follows:

“Develop autism education ‘centres of excellence’ with highly-trained teachers and professional support staff who consider the unique and complex learning needs of students with ASD in each school board. This also represents an opportunity for ongoing training and professional development of education professionals who can then transfer knowledge and skills to all learning environments, further maximizing outcomes for all students with ASD and other special needs. This is also a cost-effective approach to educating and training skilled professionals.”

Each chapter of Autism Nova Scotia has something similar already, in the form of Autism Resource Centres, and it is a good first step.

There is one model that is regarded by many autistic people and professionals as the most optimal model for an “autism education centre of excellence”.

That model is the neurodiversity library model.

The neurodiversity library model provides books, resources and information on autism from a neurodiversity and disability rights perspective, including the uniqueness of autistic culture. These libraries carry books on a variety of topics, including self-advocacy, identity and diagnosis; poetry and fiction; inclusion, education and classroom support; disability history; children’s books; and many other topics. They also carry films, colouring pages, stim toys, and information sheets and flyers.

What sets these libraries apart from most public libraries is that many of the books they carry are not usually carried by public libraries or bookstores. Importantly, the majority of materials available at a neurodiversity library are either developed by or significantly influenced by actually autistic people. This is an important distinction, as most books about autism available at public libraries are written by non-autistic parents or professionals. Furthermore, many books available at public libraries that are written by autistic people don’t always have a grasp of disability justice or autistic culture.

The first neurodiversity library, the Ed Wiley Autism Acceptance Lending Library, was started in Stanwood & Camano Island, Washington in 2014. Since then, several other similar libraries have formed across the United States, using the Ed Wiley Library’s model.

A few similar libraries have formed in Canada, as well. These include the What About Us Neurodiversity Library in London, Ontario, run by London Autistics Standing Together; a Neurodiversity Library in Vancouver run by the local chapter of Autistics United Canada, and a new library in Toronto run by A4A Ontario.

What all these libraries have in common is, they are run entirely by actually autistic people. In addition to the materials available at these libraries, the autistic people who run them are valuable resources in their own right. These elements are what makes these libraries true “autism education centres of excellence”, even if they don’t call themselves that.

So what could Nova Scotia do?

As a starting point, the various Regional Centres of Education could acquire some materials that the neurodiversity libraries carry. They could also avail themselves of educational resources such as Foundations for Divergent Minds and United for Communication Choice.

In addition, the Regional Centres of Education are encouraged to contact the existing neurodiversity libraries to learn how they’re set up to support autistic and other neurodivergent people. Most importantly, autistic-run organizations would gladly welcome the opportunity to be engaged and provide feedback, as autistic people are the number-one stakeholder when it comes to autism-related issues.

Everybody wants an inclusive environment for all children to be supported and successful in school. By meaningfully engaging those who are under-represented and marginalized, it will be much easier to achieve full inclusion.

Alex Kronstein is the founder of Autistics United Nova Scotia, the local chapter of Autistics United Canada, a grassroots organization committed to raising the voices of Autistic people. He is also the host of the podcast The NeurodiveCast, and is a documentary filmmaker with several films currently in development.

With a special thanks to our generous donors who make publication of the Nova Scotia Advocate possible.

Subscribe to the Nova Scotia Advocate weekly digest and never miss an article again. It’s free!