KJIPUKTUK (Halifax) – between 2006 and 2016 the Black population of the North End dropped by half, as over 700 Black residents left a neighborhood where many had lived for generations. That’s way more people than lost their homes when Africville was demolished.

Ted Rutland, an Associate Professor, Geography, Planning and Environment at Concordia University, argues that urban planners focused on the notion of reducing crime were one of the more significant driving forces behind this gentrification of the North End.

Rutland is the author of Displacing Blackness: Planning, Power, and Race in Twentieth-Century Halifax, a fascinating book that places anti-Blackness at the root of the urban planning discipline.

I talked with Rutland in early March, after attending his talk about the gentrification of the North End at the Gottingen Street library.

Can you talk a bit about how planners have used crime data and how that approach has shaped planning policy in Halifax?

Planners have used police data on crime to understand the urban environment going back to the very beginning of modern planning. After various cholera outbreaks in Britain, France, and North America in the 1830s we already see that the people who are trying to understand the cholera outbreak are interested in where people are getting sick, what the housing conditions are, but also, what the crime rates are in those areas.

That notion becomes central to the founding of the discipline of professional planning in the early 1900s and 1910s. During that period there are all these national town planning conferences, mostly in the United States, but a couple in Canada as well, where architects, landscape architects, public health officials, city officials, and engineers are trying to codify what planning is going to be and establish planning departments and planning programs at universities, etc.

Again there is a lot of focus on poor areas of the city, what they called slums. And the problems of the slums are things like ill health, morality and crime. In all these cases they’re using police data on crime.

In Halifax in the seventies there were all these efforts to deal with the North End, which was facing a variety of problems, including high rates of poverty. During the 1980s and 90s welfare rates continued to get cut, people in the North End became increasingly poor, and the number of local businesses declined. Planners believed that the reasons for that decline are poverty and crime, and their main strategy became to deconcentrate poverty.

| 1961 | 1971 | 1981 | 1991 | 2001 | |

| Population | 13,070 | 7,584 | 5,194 | 4,494 | 4,943 |

| Gottingen businesses | 138 | 95 | 70 | 54 | 38 |

| % employed | 75% | 58% | 56% | 60% | 46% |

| Welfare rate/ poverty line | 44% | 47% | 29% |

For instance, when Uniacke Square was first considered it was intended to contain 1,100 units, and the homes of 4,000 people were bulldozed. But then in the mid-seventies they abandoned that plan and constructed only 200 units in Uniacke Square and another 100 in Ahern Manor. Instead, the focus fell on nonprofits and housing co-ops, which tended to be for people with slightly higher incomes. That signaled the beginning of a planning policy in the North End to decrease concentrated poverty, partly because it was thought that would lead to less crime.

You also talk about planners taking on the actual job of policing. Can you give some examples?

At Uniacke Square again, the Metropolitan Regional Housing Authority made several decisions where they didn’t just collaborate with police, but also acted as police themselves.

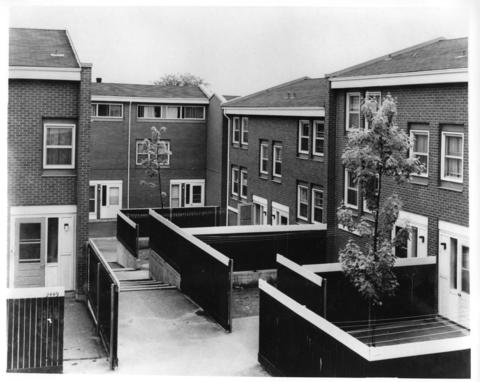

Between 1980 and 1990 there was a major redevelopment of Uniacke Square funded by the federal government. As part of that renovation they did a bunch of things that are really great. For instance, they upgraded the kitchens in the units, and they created more green space on the site. But they also implemented changes that were meant to make the area more policeable. In some places they put fencing to stop people from gathering. They also eliminated a bunch of pedestrian walkways through the Square and turned them into cul de sacs so that people would have a harder time evading the police. And they eliminated what were called galleries, which are kind of like balconies that ran along the outside of the buildings, again to eliminate spaces where people could congregate.

And then in 2004 Metro Housing gave the police a housing unit to run a community police station. That unit became the home base for all police officers that were doing foot patrols through Unique Square. They also put two full time community liaison community response officers in that community police office. Those community response officers also were tasked with being involved in the community. So they became mentors, they volunteered at after school homework programs, they participated in community basketball games, etc. I’m sure that these two officers were probably among the best cops on the force. But nonetheless you’re basically facilitating a process where poor youth of colour are going to be under police surveillance all the time. We would never do any of those things in a middle class area,

Of course residents are concerned about the crime that existed in the neighborhood, but a lot of residents also saw this as installing a police state in the neighborhood. Some people call it a concentration camp in which they’re under constant surveillance. There’s been a lot of criticism and resistance to all this.

This was an experimental redevelopment on the part of the federal government. The Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation saw this as an opportunity to implement new kinds of physical changes that would supposedly make the area more secure. These same changes have since been implemented in Montreal, Toronto and Vancouver. They come out of this idea called crime prevention through environmental design, which was developed by an architect in the United States named Oscar Newman. It’s very odd to believe that you can reduce crime through physical interventions. You don’t eliminate the root causes of crime, at best you make the area easier to police, and so you facilitate racial profiling and disproportionate rates of arrest and mass incarceration.

When you think of the North End you think of gentrification. Can you talk about that and how it fits in with this notion of crime prevention through planning?

Planners have been openly supportive of gentrification of the North End since the 1970s. You can see that, for example, in a 1986 report where it is suggested that the number of social services on Gottingen Street needs to be reduced because their presence caters to a low income clientele.

The city also targeted the North End for a residential Rehabilitation Assistance Program, using federal money. They basically gave people grants and low interest loans to renovate their homes. There were certain protections in place to mitigate gentrification, but those measures weren’t that strong. A report on the effects of that program found that the area targeted by the city had Halifax’s highest increase in property values between 1983 and 1993. So it directly fueled the early stages of gentrification of the North End.

As we discussed, from the 1970s on the city saw the deconcentration of poverty as a way of alleviating crime. Deconcentration of poverty means bringing in higher income people. So they directly supported gentrification in order to reduce crime. It’s not the only reason, but we can’t talk about gentrification in the North End if we don’t also talk about the ways in which a perspective that the area is crime prone has been part of what led to the transformation in the neighborhood.

In terms of the actual numbers, the Black population in the North End was relatively constant from the 1970s until 2006. But between 2006 and 2016 the Black population of the North End dropped by half, by over 700 people. The North End up to North Street was 30% Black in 2006, According to Statistics Canada data in 2016 that number was down to below 15%. People have been warning of another Africville in the North End for decades. And it’s happened. Some 400 people were displaced from Africville in the 1960s, and there have been close to 700 Black people displaced from the North End. And that’s actually a very conservative estimate because that doesn’t count when one Black person gets displaced and replaced by another Black person. We’re talking about net reduction of the Black population, probably at least a couple hundred more people were displaced but not counted.

What is wrong with looking at crime stats?

There are a bunch of problems with police crime data. One is that crime rates don’t actually reflect the amount of crime that happens in an area. Crime rates are mostly determined by reported crime. And we know that some people are much more likely to get arrested for breaking the law than others. So when we’re looking at an area that has major problems with racial profiling, that absolutely means that people of colour and particularly Black people are much more likely to get arrested for the same things that white people are also doing but don’t get arrested for. So the crime rate is always going to be inflated in communities of colour and poor communities because they’re over-policed.

The second thing about using police data on crime is that it forecloses a discussion about what kinds of things we actually care about. There are lots of things that are considered crimes but that are not harmful to anyone. And there are also many things that are harmful, but either are not considered crimes, or they’re not actively policed. Until the 1980s the police were not very concerned with domestic violence, and even now they’re not very good at dealing with it.

The third issue is that once you start citing police data on crime you very easily accept the idea that the police are the solution. Yet the police are not the solution to most of the things that we call harm. So you foreclose the discussion about how we are actually going to deal with community based harms.

Part of the reason I bring this up is that there’s no reason for planners to be supporting the police in this way. Why are planners so unhesitatingly supportive of a police view of the neighborhood, and why do they view policing as a solution?

In terms of alternatives, I’d like to see a discussion where we stop seeing the police as the solution to all harms. I think a better way of dealing with actual harms in communities is to center that discussion on people who have to face community-based harms and police harms. What you will find is that the solutions aren’t about the police, and that there are many ways of dealing with harms that address some of the root causes of harms, and foreground possibilities for transformative justice that are sorely needed.

Can you talk a bit about the North End and HRM by Design, the planning strategy for the Halifax downtown area that is now official HRM policy?

As early as 2006 the part of the North End closest to the downtown was identified as a gateway, an ideal place for highly paid middle class professionals to live so they could enjoy its quirky heritage buildings but also have easy access to the downtown. What makes this problematic is that the North End is seen as an extension of the downtown, rather than as a vibrant wonderful community that planners should support for the sake of the people who actually already live there.

Contrast that with what the One North End project is trying to do, making the North End a better place for everyone who lives there right now. The One North End project understands that that means putting the emphasis on the people who are most likely to be left out by HRM by Design.

In other cities around the world planners have taken up that perspective and pursued that kind of work. But in Halifax we haven’t seen that yet. I think it’s a real shame. Centering the lives and the needs of people who are left out and oppressed, people who’ve been harmed historically, is a way not just to make their lives better, but to create a better city altogether. We’d all benefit from living in a city that was less racist, that was less unjust, that was less oppressive, that was less centered on displacement in the interest of white supremacy and profit.

With a special thanks to our generous donors who make publication of the Nova Scotia Advocate possible.

Subscribe to the Nova Scotia Advocate weekly digest and never miss an article again. It’s free!

I have been living in Halifax since 2000, and I lived on the infamous “Crack Corner”, Uniacke and Brunswick Street in 2016. In 2000, 2001, to about 4 or 5 years, it was an open drug market. It got raided a lit, someone gut shot, and drug activity moved. The North end is evolving into a vibrant, cultural, fun, meeting place for many, many people. Why isn’t there ANY low income housing in the city’s new plans for the areas they are overtaking? Where are people going to be displaced to, again?