KJIPUKTUK (Halifax) – December 6 is the 100th anniversary of the Halifax Explosion. CBC radio has already devoted precious air time to pump the Halifax Explosion to the listening public. Radio One will also spend its whole day of local broadcasts on Wednesday (6 am to 6 pm) to commemorate the event.

More than 40 books about the Halifax Explosion have been published in the last thirty years. Newspapers, magazines and online resources have dedicated hundreds of column inches to it. Many public talks, church services and ceremonies are taking place to commemorate it. Canada Post has launched an original stamp to commemorate the Halifax Explosion. A local academic created a database which has tracked the names of 1,935 people from Halifax and Dartmouth who died that day. A new play Lullaby: inside the Halifax Explosion toured Nova Scotia high schools and is currently being staged at the Maritime Museum of the Atlantic in Halifax. Dalhousie Art Gallery has mounted a show The Halifax Explosion which features work done by Group of Seven artist Arthur Lismer who lived in Halifax during the time of the explosion. And there is a new choral performance called Halifax 1917: From Dreams to Despair which debuts this month.

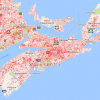

But what was the Halifax Explosion? In school, we learned that in 1917 there was an accidental collision in the Narrows in the north end of Halifax harbour. The Mont-Blanc was a French ship loaded with explosives. It collided with a Norwegian steamship, the Imo. The explosion which ensued, killed 1,600 Haligonians instantly and injured more than 9,000. At least 400 more died in the days that followed. The explosion was 20% of the magnitude of the “Little Boy” –the atomic bomb dropped on Hiroshima in 1945.

Why was a French ship loaded with the equivalent of 2.9 kilotons – 5.8 million pounds of TNT– in our harbour?

What we know now is that December 1917 was in the midst of World War I – a war which would not end for another twelve months. World War I was an inter-imperialist war in which Canadians served as little more than cannon-fodder for the Motherland Britain. For instance, our parliament did not vote to go to war in 1914 – because nearly all our foreign policies were determined by Britain. One of the main contributors to WWI was British imperialism and the fear of British methods of war – such as naval blockades and concentration camps*. The British empire (including Canada), plus France, Serbia and Russia went to war against the German and Austro-Hungarian empires.

The French vessel in our harbour, the Mont-Blanc, had sailed from New York City via Halifax en route to Bordeaux, France. Its cargo included wet and dry picric acid — an explosive used for blasting charges and stuffed into artillery shells; TNT which was used to fill high explosive artillery shells; and guncotton, a blasting agent used to make underwater warheads such as torpedoes. The Norwegian freighter, the Imo, had been chartered by the Commission for Relief in Belgium. The Commission was a mostly US-led charity which sent food to civilians in German-occupied Belgium. The Imo was en route to New York to take on relief supplies.

World War I was responsible for 7 million deaths in the military on both sides. More than 6.6 million civilians died – many from gas attacks. Chemical weapons and poisoned gas were used widely as instruments of destruction during WWI. The chemical attacks and gas drifted over civilian populations. The effect on civilians was disproportionate because people in nearby cities and towns typically had no warning of gas attacks and had no access to gas masks or any protection.

What of a 2.9 kiloton explosion in a ‘friendly’ harbour? Today we know what the 5.8 million pounds of high explosives did to Halifax, and more importantly what it did to women, children and men just going about their daily affairs.

Was the Halifax Explosion a war crime? Nearly 75 years later, the statutes of The Hague tribunal said (with reference to the former Yugoslavia) that the court could try suspects alleged to have violated the laws or customs of war such as the reckless destruction of cities, towns or villages, or devastation not justified by military necessity.

Today, we rightly condemn countries that put civilians needlessly at risk by establishing military strongholds or garrisons in the middle of civilian populations.

There was no military justification for taking Halifax hostage with a ship loaded with 5.8 million pounds of TNT in our harbour. The Halifax Explosion was a war crime.

And, unfortunately, the tributes around December 6 demonstrate that we’re proud of it.

*See Ring of Steel: Germany and Austria-Hungary in World War I, by Alexander Watson (2014).

Judy Haiven is a retired professor of Industrial Relations at Saint Mary’s University

If you can, please support the Nova Scotia Advocate so that it can continue to cover issues such as poverty, racism, exclusion, workers’ rights and the environment in Nova Scotia. A pay wall is not an option, since it would exclude many readers who don’t have any disposable income at all. We rely entirely on one-time donations and a tiny but mighty group of dedicated monthly sustainers.

A refreshing take on the Halifax Explosion. Thank you.