KJIPUKTUK (Halifax) – Food security expert Valerie Tarasuk will be visiting Nova Scotia later this week. Tarasuk is a professor in the Department of Nutritional Sciences at the University of Toronto, and a driving force behind PROOF, an interdisciplinary research team that looks at household food insecurity in Canada. PROOF releases annual reports which provide a comprehensive look at the state of food insecurity in Canada.

Tarasuk’s views on food banks, the Food Banks Canada annual HungerCount surveys, and on the relation between income and food insecurity are forcing me to rethink assumptions I always took for granted.

She also has strong opinions on how to go about fixing the problem. Not surprisingly, food banks aren’t part of the strategies she proposes. “It’s concerning how we continue to busy ourselves with these little things and further entrench these responses, as if it is somehow going to do something about food insecurity,” she says. Instead, Tarasuk argues for evidence-based policies firmly targeting food security rather than mere income thresholds.

We talked to her over the phone earlier this week.

On food banks not addressing food insecurity, and hunger counts not counting all hungry people

We mostly use data collected by Stats Canada. Since 2005 the Canadian Community Health Survey has included this 18 item questionnaire on food insecurity. That survey itself is a very big thing, very sophisticated. The sample is about 60,000 people, carefully designed to be representative, there are weights applied to account for non-response, and so on.

We have known for a long time that most people who are food insecure don’t use food banks. What we see over and over again is that the number of people who live in households that at some level experience food insecurity is 4.5 to 5 times higher than the number of people that are reported in any one year to be using a food bank. That’s a big difference.

Researchers have known this for a long time. But for ordinary people it’s startling. For so long in Canada we have had these annual HungerCounts. Even the name hunger count suggests it counts the number of people in Canada who are hungry. But it doesn’t. It counts the number of people who use a particular kind of service. The HungerCount reports recognize this, but the slippage occurs when the media gets hold of them.

The discrepancy between food bank use and food insecurity tells us that the problem is way bigger than we thought it was. As we delve more deeply into the demographics of the people who are food insecure, or consider the health implications, the other thing we can say is that the problem is also way more serious.

The image of the problem that you get when you think about food banks is that somebody doesn’t have enough food, so we must give them food. It feels so straightforward and immediate.

But when we look at the research about food insecurity, we say no, this is not a small problem, and isn’t solved by giving somebody a bag of food. We have people living in chronic conditions of deprivation that have profound implications for their health and well being. Yet what is communicated in the appeals for food bank donations is that you just have to give, and we are managing this problem.

The link between low income and food insecurity isn’t as straightforward as you’d think, and why that should matter to politicians

No question, income is a very strong predictor of food insecurity. The lower the income, the higher the likelihood. But when we look at the stats we can find people who have very low incomes, but who are food secure. We can also find people with incomes above formal poverty thresholds who are experiencing food insecurity. Then you wonder, what is going on here?

This question forces us to think about the complexity of the multiple factors that come to determine somebody’s level of deprivation or well being.

It is not enough to say we want to reduce the number of people who live on low income. We want policy makers to say we want to reduce the number of people who are food insecure,

Whether you have assets, home ownership being key. When you own your home, you have an asset you can borrow against. The other part is debts. People with mortgages are more vulnerable than somebody who owns their home outright. Maybe we’re dealing with a senior who owns her home outright and has very little cash flow but in fact is a very wealthy person.

For me, learning that was an important thing because it has policy implications. It is not enough to say we want to reduce the number of people who live on low income. We want policy makers to say we want to reduce the number of people who are food insecure,

Justin Trudeau talks about how many hundreds of thousands of people have moved out of poverty through the Canada Child Benefit. I want him to say how many children no longer live in food insecure households. My guess that is not near as big as the numbers he mentions.

Food insecurity and health all tangled up

When we first started to study food insecurity we thought we were studying a nutrition problem. In the early days we focused on dietary intakes of food insecure people, and looked at the probability of diabetes or heart disease, or high blood pressure, ailments that are associated with diet.

We also look at healthcare costs associated with food insecurity, We see a very strong relationship. The more food insecure, the greater the number of healthcare dollars a person will use in a the course of a year.

Then we started looking at other conditions, like anxiety, depression arthritis, asthma, things that don’t have much to do with diet. We found that these things correlated very highly as well.

It is complicated. I haven’t totally figured it out yet. But what we can say is that an adult who is in a food insecure situation is more likely to manifest with a whole bunch of health conditions, no matter whether they are diet related.

The strongest association we see is with mental health, not physical health.

The strongest association we see is with mental health, not physical health. We found that people who are food insecure are way more likely to use healthcare for mental health reasons, whether it is going to an emergency department or a psychiatrist. They are also way more likely to be hospitalized. That speaks to the severity. This happens because the mental health condition is completely out of control. That makes sense when you think about about the extreme stress parents especially would be under if they are food insecure, Of course they wouldn’t be able to manage their health conditions, because their lives are so hard.

What works, and what doesn’t

We have two examples that speak to the nature of possible solutions. The first one is that we see a sharp drop in the risk of food insecurity after the age of 65. The only thing that changes is that these people become eligible for old age pension and guaranteed income supplements. For somebody on welfare it will be double what they were getting before, and it will be indexed to inflation. It will typically come with full drug benefits. What happens is that we have an income floor. It’s not perfect. But there is strong relationship that when you give people an income floor that is closer to adequate than it dramatically drops the risk of food insecurity.

The other finding we have is the poverty reduction strategy launched in Newfoundland and Labrador in 2005. As a result we saw a sharp drop in food insecurity rates in the province. Quite a bit of that drop could be accounted for by the changes that had been made to social assistance. They raised the rates, indexed them to inflation, they did a bunch of things to improve the circumstances for people on social assistance. Food insecurity dropped by 50% amongst social assistance recipients.

The Newfoundland experience is important because it didn’t just reduce the number of people below some income threshold, but also the depth of poverty. They improved social assistance even though people on social assistance still didn’t have an income that would take them above any poverty line. But it really improved their living circumstances.

It’s concerning how we continue to busy ourselves with these little things and further entrench these responses

What is discouraging to me is the number of government initiatives that continue to fuel food banks as a response. Many provinces have introduced tax credits for farmers who give to food banks, back in the nineties we had these good Samaritan laws that absolved corporate donors from liabilities in terms of the health and safety of the food donated.

It’s concerning how we continue to busy ourselves with these little things and further entrench these responses, as if it is somehow going to do something about food insecurity. It’s not accountable. It’s very cheap for government to make these gestures, as opposed to revamping the welfare system, to make it so that people are no longer food insecure.

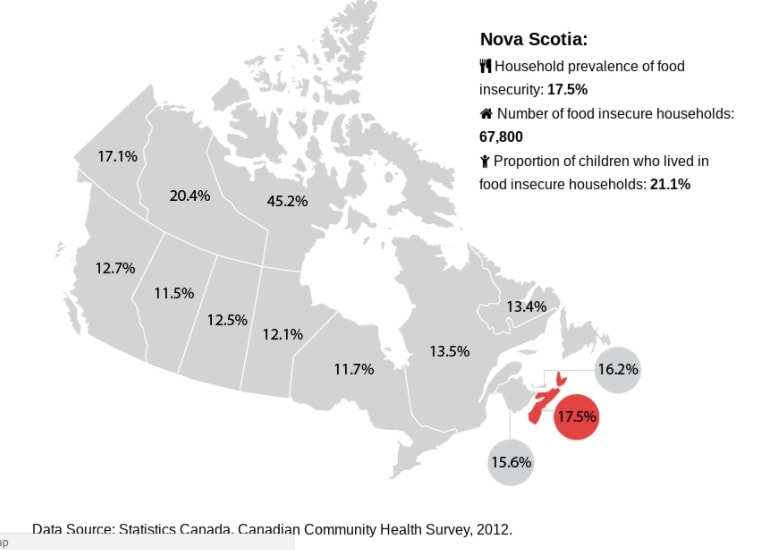

According to most recent data, in Nova Scotia 82% of income assistance recipients reported experiencing some kind of food insecurity. That’s ridiculous.

According to most recent data, in Nova Scotia 82% of income assistance recipients reported experiencing some kind of food insecurity. That’s ridiculous. We don’t need governments talking about food security strategies as if it is all about funnelling more resources into food charity. We need a food security strategy that is tackling that 82%.

See also: More hunger in Nova Scotia than any other province, report finds

Valerie Tarasuk will give a public talk this Thursday, May 3, at 2 pm, at the Central Library on Spring Garden Road. The event is hosted by the Community Agenda for Social Assistance Reform.

If you can, please support the Nova Scotia Advocate so that it can continue to cover issues such as poverty, racism, exclusion, workers’ rights and the environment in Nova Scotia. A paywall is not an option, since it would exclude many readers who don’t have any disposable income at all. We rely entirely on one-time donations and a tiny but mighty group of dedicated monthly sustainers.

Excellent interview. Hope this gets traction in the government. Social assistance needs to be adequate to allow people living with disabilities to maintain their health.