KJIPUKTUK (Halifax) – At Northwood, Atlantic Canada’s largest long-term care centre, five residents have died from Covid-19 in the last five days That accounts for just over half of the deaths due to the virus in the whole province.

Some residents have recovered, and starting Sunday, at least 20 of those will be moved to a hotel. As of April 22, there were 112 Northwood residents and 40 staff who tested positive for Covid-19.

How can Northwood, the preeminent not-for-profit long-term care facility in Nova Scotia, one that was only last year accredited “with exemplary standing,” be in such a desperate situation now?*

Several things converged – most were predictable but some were not.

Design of nursing homes: built on a mini-hospital model

First, like many long-term care homes across the country, many of the 485 residents of Northwood are housed two to a room and share a bathroom. Nursing home designers and architects have to answer for building institutions on this model

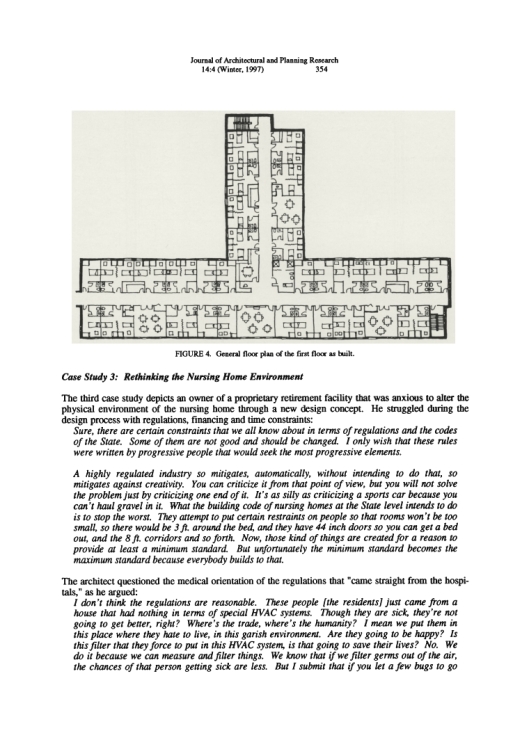

From Schwarz’s article “Nursing Home Design”

According to one US-based architecture professor, Dr Benyamin Schwarz, nursing home architecture seems to “clash with efforts to satisfy the non-medical needs of the frail elderly.“ In a very interesting article, Schwarz writes that nursing homes must cater to competing interests which include those of the residents, the medical teams, the government which controls their financial strings, the institutions’ economic exigencies and the social needs of the elder community.

Schwarz acknowledges that

“… the public health services experts who drew up the requirements [for nursing homes] were heavily affected by their hospital orientation, which is why to this day most nursing homes look so much like mini-hospitals.”

Nursing home design from 50 or 60 years ago often had residents share a room, which housed more seniors, possibly more cheaply. But two to a room can present risks to the health of residents. Economizing sounds attractive to the for-profits because when they double-bunk, their profits ratio go up.

While profit is not an incentive for Northwood, accommodating two to a room does increase capacity, without the cost of building a new or expanded structure. With residents sharing sleeping space so closely, plus toilet and bathrooms, any virus can spread easily in the building.

Aside from the obvious health risks, nursing homes’ box-like and crowded settings are themselves a problem. As Schwarz points out,

“If the depressing and frightening setting of the American nursing home reflects our collective moral heart – it is fairly grim.”

Above are drawings of a traditional double room, and single room for a conventional nursing home. Here’s how most nursing homes are designed: the long hallways, with little natural light, means residents park themselves in their wheelchairs in the hallways for social contact.

From Schwarz’s article “Nursing Home Design”

Schwarz finishes his exposé this way:

“… society should be able to create a better architectural model for frail elderly which asserts their rights and freedoms for a fulfilling old age This is not a utopian goal.”

Cuts to long-term care budgets

Second, two successive McNeil governments have cut the budgets of most of the province’s 132 nursing homes and residential care facilities. In 2015-17, the Liberal government reduced grants to long-term care by $8.1 million.

Northwood’s president and CEO, Janet Simm, said the 2016 cuts amounted to $360,000 for her institution; in 2017 the cut was nearly $600,00. While Northwood undertook group purchasing and other measures to economize, the biggest challenge was food. In part this was because more and more residents had special diets. On average, nursing homes spent $6 per resident per day for food. Some residents complained that a meal supplement drink (such as Boost) was offered at meal times in order to trim the food bills.

Cuts to food

Northwood’s Janet Simm noted,

“With rising costs of food and the decreasing budget, it’s a real challenge to meet the growing demands. This is where people live and you want to make sure the food is high quality because it is a big piece of quality of life.”

See also: How can it not affect them? Residents pay for government austerity, long term care workers say

UNIFOR, one of the unions that represents workers at Northwood, agreed that the quality of care was affected by the cuts; staff hours were cut, so there was less contact time with residents.

This photo of a plate of baked beans and potatoes was taken by Colin Sproul, April 29, 2017, a month before the provincial election.

This was the meal served to Sproul’s mother at a transitional care unit inside Middleton Soldiers Memorial Hospital, where his mother had been waiting for a long-term care bed. Sproul said,

“This is a direct consequence of Stephen McNeil’s cuts in Annapolis County and the effect it’s having on people,” Sproul was the NDP candidate in Premier McNeil’s riding of Annapolis.

It was just before the May 2017 election that I ran into the Premier himself, who was electioneering along the boardwalk on Halifax’s waterfront. I stopped him, introduced myself, and asked him if he would have cut a nursing home’s food budget if his mother had lived there. He became furious – so angry that his principal secretary at the time, former CTV news reporter Laurie Graham, had to pull him away, insisting they had to go.

Just before the May 2017 election, NDP leader Gary Burrill, in a bid to restore the $8.1 million McNeil’s government cut from long-term care, promised that –if elected—an NDP government would put $8.3 million back into long-term care.

In his 2017-18 budget, McNeil reinstated $3.2 million.

Then, in the 2019-20 budget, the government added a further $2.8 million. But to fully restore that initial $8.1 million and inflation, the government would have had to add $8,764,120. Instead the McNeil government restored a total of only $6,000,000. So there was a net loss of funding to long-term care of $2,764,120.

Still, in the government’s defence, from 2013-2016 the Liberals did put $55 million into homecare. The idea was to support seniors who wanted to stay in their own homes. In fact, at the time, increased funding for homecare was a trend in government budgets right across the country.

Though Anthony Taylor agreed homecare deserved to be bolstered, not at the cost of long-term care. Taylor is the administrator of the 111-bed nursing home, Oakwood Terrace, in Dartmouth. In 2015, Oakwood suffered a budget cut of $82,000, and in 2016 another cut of $86,000. Said Taylor, “Those two years, back to back, this government has cut more money from this nursing home than any other government has done to this home in the 34 years we have existed.

The crisis in staffing: before and during Covid-19

Finally there is the issue of staffing before and during the Covid-19 crisis. Regulations call for one Licensed Practical Nurse (LPN) to care for up to 30 residents, and a Registered Nurse (RN) is meant to be on the premises 24 hours a day. Both these rules have been contravened many times in nursing homes across NS, which frequently “run short”—meaning fewer care workers than needed.

These are workplaces that pay from $17-$25 per hour (of course the RNs earn more). Before you call that a good wage, think about this: would you do the physically demanding and tedious work of an LPN, or a personal care worker for $20 an hour? Given full time hours, you could earn about $40,000 per year. However, in Nova Scotia with the budget cuts to long-term care, many LPNs and care workers whose hours were cut in one home, have to work at part-time jobs at one or two other long-term care homes to earn enough to live. In today’s reality of Covid-19, why would you — as a low-paid care worker — sacrifice your own health and that of your family to work in one, two or even three care homes?

See also: Staff shortages at long term care facilities are unsustainable, workers say

A week ago, in response to the pandemic in that province, Ontario’s premier issued a new emergency order that prohibits nursing home staff from working at more than one facility. This was done to help contain transmission of the virus by the staff who could carry it from one care home to another.

Premier McNeil has declared no such rule in NS.

In terms of Covid-19, Public Health in Nova Scotia knew what was coming. It was around St Patrick’s Day, when Halifax’s downtown Irish pubs decided that due to Covid-19 they would close their doors to revelers. It was a few days later that Public Health, in a bid to limit crowds and gatherings, ordered every other table remain vacant in restaurants, cafes and bars. Days later, all restaurants, cafes and bars had to close (except for limited take-out service).

Dangers in confined or crowded spaces

This brings us to the point about dangers facing groups of people in confined spaces. Nova Scotia closed all schools, from daycares to universities. Gyms, libraries, theatres and community centres also had to shut. But there was little to no attention paid to nursing homes and elder care residences. However, many public health experts know how dangerous viruses can be to residents of nursing homes, as this quotation from an article in a journal Clinical Infectious Diseases illustrates:

“The common occurrence and dire consequences of infections disease outbreaks in nursing homes often go unrecognized and unappreciated. Nevertheless, these facilities provide an ideal environment for acquisition and spread of infection: susceptible residents who share sources of air, food, water, and health care in a crowded institutional setting. Moreover, visitors, staff, and residents constantly come and go, bringing in pathogens from both the hospital and the community.”

While nursing homes could not be closed, arrangements could have been made. The arrangements we see at Northwood today such as devoting a floor of the building to isolating those who test positive, or assigning a floor to those recovering, could have been made sooner. When did Northwood begin spatial distancing measures such as moving people from double to single rooms, or if that option was off the table, moving some healthier residents who required less care to hotel rooms?

Pandemic and prisons

Public Health warned us a pandemic was coming to all regions of Canada. By early March we all knew. Now seven weeks later, as a result of mandatory social-distancing and isolation we are seeing a slight fall in the community spread, but deaths in nursing home are rising.

Prisoner rights activists, and lawyers representing prisoners, have warned us that prisons will become a killing ground for prisoners and jailers alike once Covid-19 begins to spread inside. The prison guards go home to their families after their shifts, and return to the jail every work day.

We didn’t heed the warnings in time to save thousands of elderly people in institutions across the country. Are we listening to the warnings about the risk to the prison populations? They will be the next Covid-19 frontier.

Notes:

Schwarz, Benyamin. 1997. “Nursing home design: a misguided architectural model,” in Journal of Architectural and Planning Research, 14.4, pp. 343-359,

Strausbaugh, L, Shirin, et al. 2003. “Infectious Disease Outbreaks in Nursing Homes: An Unappreciated Hazard for Frail Elderly Persons,” in Clinical Infectious Diseases, Vol. 36, No. 7. Pp. 870-876

* There is no clear list of which NS long-term care facilities are for-profit and which are not-for-profit. The provincial government’s directory here does not distinguish. But I suspect the majority of nursing homes are in the for-profit category. And that is a problem just as for-profit child care centres are problem; there is evidence that for-profit child care centres tend to skimp on quality food, toys, and outings, not to mention lower staff salaries in an effort to bring higher profits to the owners.

See also: Letter: In Nova Scotia long term care is underpaid, undervalued, understaffed and underfunded

Judy Haiven is on the steering committee of Equity Watch, a Halifax-based organization which fights bullying, racism and discrimination in the workplace. You can reach her at equitywatchns@gmail.com

With a special thanks to our generous donors who make publication of the Nova Scotia Advocate possible.

Subscribe to the Nova Scotia Advocate weekly digest and never miss an article again. It’s free!