KJIPUKTUK (Halifax) – We see condos and luxury apartments go up all over the place, we hear about renovictions, and rent surveys show how expensive housing is becoming. Anecdotally we hear about people on income assistance leaving the city and returning to rural Nova Scotia where they have roots, not because they want to, but that’s all they can afford.

Given all that, it’s surprising how little we really know about the effects of all this on Halifax’s neighborhoods and rural communities.

Last year we published a brief story on a report that tries to address this lack of knowledge. Halifax, a city of ‘hotspots’ of income inequality. That report looks at demographic trends over a thirty-year period in all of HRM.

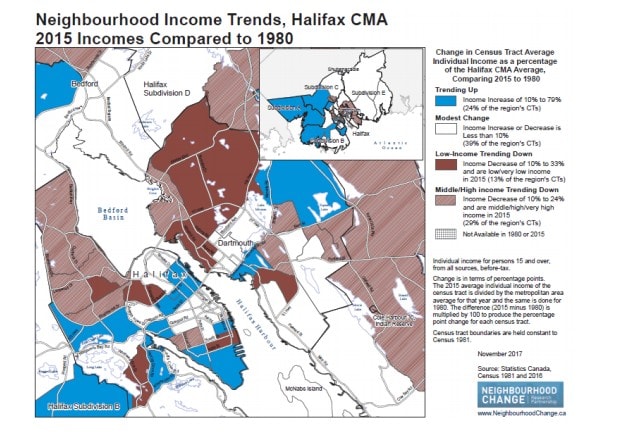

The report shows how since 1980 much of Dartmouth North, suburban Dartmouth, Spryfield, and Clayton Park transitioned from middle-income to low-income areas. In rural HRM there are similar trends in the municipality’s ‘rural east’, the Prestons. This downward movement accelerated during the nineties when austerity was particularly severe.

Neighbourhoods that are trending up, those experiencing increases in their average income between 1980 and 2015, are located in downtown Dartmouth, suburban Dartmouth, the North End and the South End as well as new off-peninsula developments in the western part of HRM such as Tantallon along Highway 103.

See also: Halifax’s shifting landscape of wealth and poverty

I always felt it was an important study and wanted to write more about it. That’s why this summer I approached Dalhousie professor Howard Ramos for an interview. Ramos is a political sociologist who investigates issues of social justice and equity and who, together with Kathleen MacNabb, co-authored the report.

Your report focuses on income inequality, polarization, and also looks at longer term trends. In terms of gentrification, what are the take-aways?

In Toronto and other larger cities in Canada the core is becoming more affluent, and as you go further out, there is more inequality. In a city like Halifax, we have much more of a hotspot of change, where you have polarized adjacencies within neighborhoods, side by side, and it’s driven by some interesting trends.

In some cases there is evidence of gentrification as we see in the North End. But in that same neighborhood there are also social housing developments and coop housing that aren’t going to change. So you end up with an increase on the top end, but you also have anchors that keep (less affluent) people present.

You also see a concentration of people who would have been pushed out from other areas that are now in North Dartmouth. Meanwhile, downtown Dartmouth is experiencing what the North End experienced maybe 10 or 15 years ago.

So it’s a little bit more complicated in Halifax than just gentrification. It’s more of a hotspot trend, where there are some things that anchor people with lower incomes in areas, but then you also see this deep contrast very nearby. And this is something that I think is important in Halifax. We don’t have a stark contrast yet, but we do have meaningful inequalities and differences.

So why are these patterns different here in Halifax than say Toronto?

Well, I think that there’s a number of things that contribute to the different paths. Part of it, as I was saying, is that there is some anchoring in terms of social and coop housing. There’s also geography, especially on the Dartmouth side, we have topography, things like lakes and oceans, that shape what our communities look like.

And yet another thing that makes it a bit more complicated or different in Halifax is that the HRM is such a huge piece of geography. We actually have some very rural communities within what’s called Halifax. Places like Sheet Harbour, or, or even the Prestons are largely rural. And that leads to different kinds of trends throughout the city.

Is there anything that you felt was particularly striking you when you started looking at the results of the analysis?

I think is important to note as part of the conversation that in a city like Halifax we often focus on neighborhoods like the North End. That focus masks a lot of the things that are going on in places like Fairview, which is going through a period of transition, or in some of our more rural areas, such as Sheet Harbour, and how we think of these areas. The trends that you see in HRM’s eastern rural areas are quite alarming, and I don’t think they get the attention that they deserve.

I think the benefit of the work that we’ve been doing is that it’s not just focusing on one neighborhood, but that it looks at the whole city. So it highlights the hotspots that are being missed by people who aren’t necessarily looking at the whole city.

If you consider communities along highway 103, or you look at places like Tantallon, these are areas that have gone through profound shifts and profound changes. Some of the communities on the number 3 highway used to be fishing villages, and now are largely bedroom communities with people working in the city. And that’s led to a very substantial change, in terms of not only the cost of the housing but also the whole culture of the areas.

What are some of the considerations as we digest the report’s findings?

Certainly in Halifax all of the construction that’s happening around the city is hard to miss. What’s interesting and what’s different in Halifax is that a lot of that construction aren’t condominiums, but are apartment buildings. However, they are often luxury apartment buildings with high rents.

It is important as part of the conversation to consider how affordability is brought into the development of these new condominiums and apartment buildings. Are they big enough for families? Are they affordable for a person with a median income? These are the kinds of questions that are important to ask and to follow up on because today, a lot of the new construction really is pricing out the average person.

There’s a lot of debate over rent control, and whether it works or doesn’t work. But it’s certainly clear that the lack of rent control and incentives for landlords to have more gradual increases in rent have led to some people being pushed out of neighborhoods in the city.

Another thing that’s important is that in Canada housing is a multi-jurisdictional issue. So it involves municipalities as well as the province and the feds. There has been some movement in the last few years to create a national strategy. That coordination is really something that needs to be worked out further.

Two academic initiatives that professor Ramos is involved in, the Neighborhood Change Research Project, and the Perceptions of Change Project have published extensively on topics discussed in this story.

With a special thanks to our generous donors who make publication of the Nova Scotia Advocate possible.

Subscribe to the Nova Scotia Advocate weekly digest and never miss an article again. It’s free!